Review of ‘Interlaced Journeys: Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art’

Generative proposals for re-examining the diaspora

By Ho See Wah

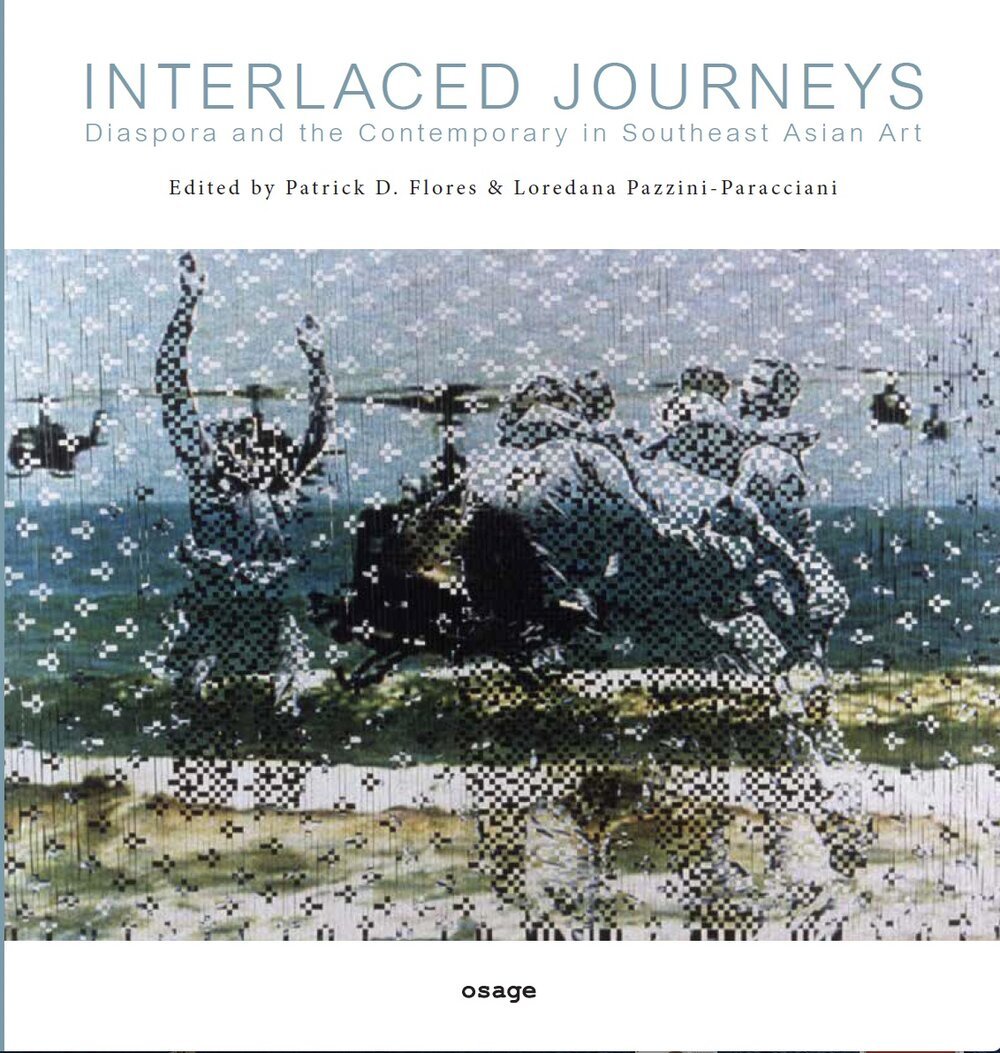

Book cover of ‘Interlaced Journeys: Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art’.

‘Interlaced Journeys: Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art’ is an invitation to expand our perceptions of diasporic art. The anthology, co-edited by Patrick D. Flores & Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani, positions itself as a starting point for dissecting this concept in a manner that will spur multiple ways of perceiving such artworks from a uniquely Southeast Asian perspective. At the same time, the editors acknowledge that the collection of essays are in no way a comprehensive take on this mammoth subject. “While the book tries to cast a wide net in terms of the perspectives and backgrounds of the contributors, there’s still a long way to go in gathering a wider range of references and frameworks to reach a level of complexity”, says Flores and Pazzini-Paracciani. Instead, they see ‘Interlaced Journeys’ as the beginning of a multifarious conversation which promises “a prism of possibilities”, as Pazzini-Paracciani writes in the introduction.

When contextualised against Southeast Asian geographies and bodies, intersectionality is key. Scholars writing about the region will be quick to point out the immense diversity of the region, making it a herculean task to concoct a cohesive understanding of its many attributes. In fact, the question might be why there is even a need to do so. Conceptually, Southeast Asia is useful to a certain extent, but to totalise it as such is unhelpful, given that narratives and identities are potentially constrained by its geopolitical constructions. This is where Flores’ preface, which dissects the idea of the geopoetic, is constructive in expanding our notions of Southeast Asia and its diaspora. The editor says, “The geopoetic premise enables us to view how art and place produce each other, rather than perceive the art as a mere function of the place and of art as transpiring regardless of the place.” This framework as an analytical tool deftly guides us through the essays.

In the spirit of multiple interlacements, a “hybrid thinking” approach is adopted. Contributors include curators, artists and historians, and curatorial engagement is in conversation with academic research. This is particularly advantageous as it allows for multiple perspectives to come through, which enables the editors’ intent of inducing a lively, pluralistic conversation. The book is divided into three sections: ‘Locality and Movement: Redefining the ‘Diasporic’ in Southeast Asian Art Practices’, ‘Art, Politics and Diaspora’ and ‘Transpatial Bodies: The Artist in the Diaspora’, and essays are grouped accordingly under these thematic strands of enquiry.

Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, ‘Vessels’ (after the “Fleet” project), 2015-2017, cardboard and wood. Image courtesy of MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum and Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani.

Setting the tone for ‘Locality and Movement’ is art historian and curator Eva Bentcheva’s chapter, ‘Distinguishing Artistic Mobility from Diaspora through Philippine Art History’. Through examining a select few exhibitions focused on Filipino artists, Bentcheva disrupts our conceptions of the diasporic identity. She dissects how shows such as 'Home & Abroad: 20 Contemporary Filipino Artists’ (1998-1999), a travelling exhibition organised by Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, and ‘Triumph of Philippine Art’ (2013-2014), first showcased at George Segal Gallery of Montclair State University, New Jersey often frame diasporic artists within the rhetoric of displaced persons who are always looking back at their homeland. Such framings reduced the artists and their artworks into caricatures for a nationalistic agenda. From the get-go, the reader is made aware of the tension between geopolitical constructs and lived realities, which firmly cements the value of the geopoetic as an alternative way of seeing.

As a counterproposal, Bentcheva argues for looking at artists through their artistic mobility currencies as a way to resist the baggage of the diasporic construct in curatorial and art historical frameworks. Bringing in Venice Biennale’s 2015 Philippine pavilion curated by Flores, ‘Tie a String Around the World’ as a cross-reference, the author explains how the pavilion complicates the idea of artistic mobility, where personhoods are “evolving formations which are always in a state of “becoming””. It reveals to us another viewpoint that does away with the reducibility of artists to their “origin”, and instead casts them as agential beings. It is a useful conceptual ground to stand on, particularly as the later essays continually cross-examine the various manifestations of the diaspora and artistic mobility.

Vandy Rattana, ‘Kampong Thom’ from the ‘Bomb Ponds’ series, 2009, digital c-print, 98 x 111cm. Image courtesy of SA SA BASSAC and the artist

A chapter that strikes a loud chord for the ‘Art, Politics and Diaspora’ section is ‘Recollecting Collateral Damage: Diasporic Artists and the American War in Viet Nam’, penned by Cathy J. Shlund-Vials, Professor of English and Asian/Asian American Studies, University of Connecticut. Memories of the American War (1955-1975) are still fresh, and it is little wonder that many, including the diasporic community borne from this war, continue to recall its traumas. Shlund-Vials conducts a visual analysis of the works of Vietnamese-American artist Dinh Q. Le, Cambodian artist Vandy Rattana and Lao-American artist Sayon Syprasoeuth. Her dissection posits art as a way to re-configure the narrative of the war to focus on its collateral damages. This is similar to how Rattana’s ‘Bond Ponds’ series spotlights the bombing of Cambodian civilians by American forces, a fact that was not acknowledged for years. At the same time, Shlund-Vials illuminates how artworks produced by the diaspora can also offer “possibilities of the present”. She uses Syprasoeuth’s ‘Birth of the Dragon Lady’ as an example, where the suggestion of rebirth comes out strongly. This is congruent with the chapter's position of the war’s diasporic artists as being part of an ongoing, generative conversation. It does well in showing how such artists can become active interlocutors in the political project of working through identities and histories from the American War.

Tintin Wulia, ‘(Re)Collection of Togetherness - Stage 6’, 2011, installation, interactive performance, and single-channel video. Photo by Pauline Guyon. Image courtesy of Espace culturel Louis Vuitton and the artist.

Comparatively, ‘Transpatial Bodies: The Artist in the Diaspora’ is a more adventurous section, in the way that it pushes our conceptual understanding of the diasporic identity. This is well exemplified in writer and researcher Brigitta Isabella’s chapter, ‘Dwelling in Travel as an Aesthetic Practice’. Isabella examines the practices of Indonesian artist Tintin Wulia and duo Ahmett Salina. Here, mobility is a method, and the artists exploit their ability to roam both as a way to resist pigeon-holing and to build communities and ecologies beyond national boundaries. It makes sense as a closing chapter against the background of increasing ‘dislocatedness’ and porous ideas of borders. However, this should be approached with caution as choosing to be mobile and being forced to be mobile are two very different realities, with the latter bearing the heavy weight of harsh political and social circumstances. Nevertheless, it is interesting to rethink these “displaced forms of identity through their constant act of dwelling in travel”. After all, it is the intent of the book to precipitate conversations, and this chapter provides yet another lens with which to do so.

‘Interlaced Journeys’ concludes on an inspiring note with a postscript by Nikos Papastergiadis, Professor at School of Culture and Communication, The University of Melbourne, in ‘The Global, the South, the Cosmos’. In light of the many proposals for re-capturing artists’ agential qualities amidst expanding notions of the diaspora, Papastergiadis’ postscript persuades us to welcome the profusion of “cosmos”, multiple worldings with equal validity, amidst contemporary conditions and conceptions. His concluding remark that “the globe in globalization is not the same as the cosmos in cosmopolitanism” is a particularly useful and hopeful framework for understanding networks and communities from beyond a single episteme.

All in all, the book is an informative and uplifting read. Thinking about the diaspora would customarily invoke ideas of displacement, generational traumas and damage. Yet, ‘Interlaced Journeys’ does well in excavating new meanings, and encourages optimism through reinstating agency for these communities. It is a useful piece of literature to have for Southeast Asian art scholarship, particularly when it comes to crafting an art history away from the euro-centric canon. With hope, the book will generate pertinent conversations for regionally-centred perspectives.