Review of An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’

Photographs Of The War In Our Mind

By Mai Huyen Chi

As part of an exchange collaboration with Matca, an independent non-profit initiative dedicated to photography, we present the second of three articles that explore various aspects of image-making. They are republished weekly for three weeks, on A&M with Matca's permission.

Cover of An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’. Photo by Le Xuan Phong.

The war is not present. Not directly at least. The photographs are of people existing in stages of life that are in personal relations to war. While classic war photography enters and shapes our collective consciousness of the event by delivering immediate emotional impacts, An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’ presents a slower, contemplative way of seeing.

In Lê’s ‘Small Wars’, we don’t see combat. We see war being psychologically remembered, processed, relieved, and rehearsed. We don’t look at war itself. We examine our own thinking of it.

Spanning over a decade, the photobook binds together An-My Lê’s three series: ‘Viêt Nam’, ‘Small Wars’, and ‘29 Palms’. In ‘Viêt Nam’, Lê returned to her birth country, capturing its revival after the war. With ‘Small Wars’, Lê journeyed with American reenactors of the Vietnam War. The most current of all, ‘29 Palms’ was documentation of US military exercises for upcoming maneuvers in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Leafing through the books, one finds themselves in three different worlds, aesthetically and psychologically, albeit complementing one another under the same theme. There is also a sameness: the camera of choice, black-and-white film, the large format. Framings differ, so do presentations of landscapes. The change probably reflects the photographer’s evolution of perspectives on the subject of war.

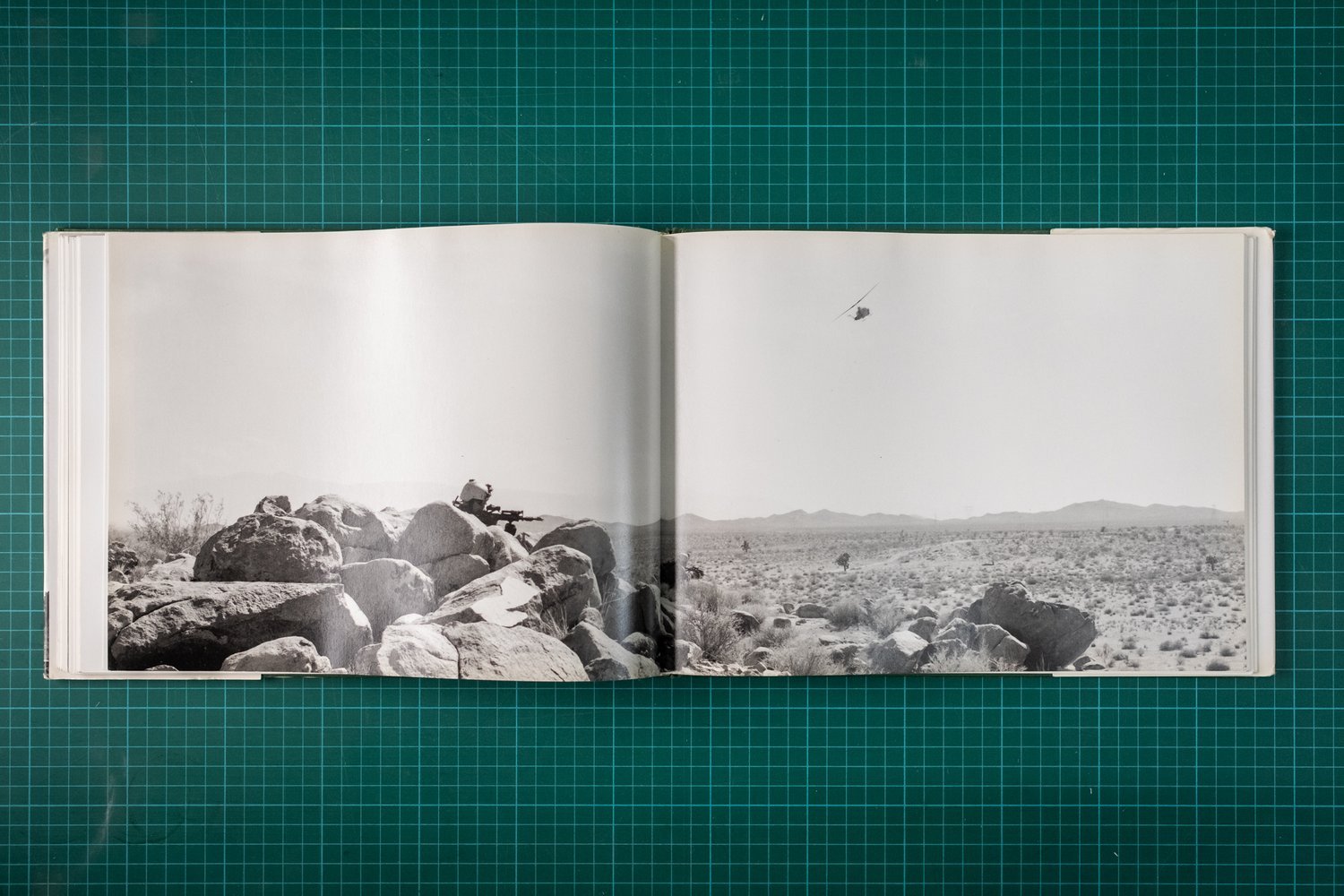

Spread from An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’. Photo by Le Xuan Phong.

Spread from An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’. Photo by Le Xuan Phong.

The photographs of Vietnam are eerie and soft. They lead us on a journey across a post-war Vietnam with seemingly no geographical nor thematic order.

In a portrait, a girl wears a beaded necklace as a badge of hope and innocence. Her head is covered by an oversized, old pith helmet – a remnant of the war that she carries as part of her current life.

In a landscape picture, civilians casually swamp a clearing, all looking up to the kites that dart in blurs across the sky. The darting and diving kites call to mind bombing airplanes that once shattered the same sky.

In some other still-life shots, we find ourselves staring at photographs of a lush forest or a desk and a chair in an empty nondescript room.

The framings are usually not clean. Nor sentimental and calculated. There is sensitivity to composition. But nothing is formalist.

There is softness and fluidness in the way Le deals with motion and lighting. In the way that photographs cut instants out of the world, she does not hurry in grasping the moment. It’s not what she is after. Her timing does not try to be the kind Henri-Cartier Besson pursued. It does not carry within itself the immediacy, the cheeky opportunism, but rather, is the result of a long, careful, unassuming gaze. With the lighting, the eye’s attention is spread, in most cases, evenly across an image. Nothing is given more importance than others. Our eyes wander the photograph, from one detail to another. Our interpretation takes time to happen. We enter the photographic world, slowly process it, slowly detect what it evokes in us.

This echoes the journey Le had when she returned to Vietnam in search of a specific answer to her past. The real that her eye/camera saw did not match what her mind had. In the end, Le resorted to “photographs that use the real to ground the imaginary”. The real she came to see was not the intended destination, but its reconciliation with her memories. The reconciliation did not happen in the immediate act of seeing. It happened in the mind after.

‘Viêt Nam’ is the most intimate series in the volume. It was the photographer’s personal quest to examine her relationship with a country that used to be home but was no longer. War was not the subject. War was a catalyst. Her journey to post-war Vietnam was, in essence, one to make sense of her own baggage, to make peace with what had happened and what had remained in her mind.

Spread from An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’. Photo by Le Xuan Phong.

Spread from An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’. Photo by Le Xuan Phong.

In ‘Small Wars’ and ‘29 Palms’, war grows into a dominant theme. The photographer’s mind’s eyes turn from the inward into others, from autobiographical to commentary. The juxtaposition is fascinating. ‘Viêt Nam’ looks in the eyes of the ordinary Vietnamese people, whom War had happened to and was pulling away from. In the latter series, we see the American people acting to bring themselves closer to War (to make War happen to them). In ‘Small Wars’, we see non-military Americans restaging the Vietnam War in Virginia’s landscapes, bringing themselves closer to a war in the past. In ‘27 Palms’, American marines rehearsed on American desserts, readying themselves to get closer to a future war they chose to enter.

But again, all of these are not War. They are its simulations. “The concept of simulations that are once removed but allow one to see and understand the real thing with clarity and perhaps more objectivity”. Distance seems a key thing, conceptually and psychologically.

The artist keeps the distance. We occasionally see a portrait. But none is a close-up that appears an intrusion of space, a kind of proximity that crosses borders between strangers. The artist doesn’t claim to be in the position of knowledge or understanding. She does not seek to shock, enrage, make statements, rouse sadness, indignance, or pity. Her position is personal but unimposing, sensitive but unsentimental, unassuming, and unintrusive.

“Her position is personal but unimposing, sensitive but unsentimental, unassuming, and unintrusive.”

This goes hand in hand with Le’s choice of large format and black-and-white film. In her words, “in an image from 5-by-7 negatives or larger, one can sense the volumes of air moving between things and inside spaces”. This distance, this air, this depth creates a naturalism that takes the viewer in with ease, stirs her in quiet, and wraps the images in a contemplative mood. “The world as seen in black and white also feels one step removed from its reality, so it seems fitting as a way to conjure up a memory or to blur fact and fiction.“

Spread from An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’. Photo by Le Xuan Phong.

Spread from An-My Lê’s ‘Small Wars’. Photo by Le Xuan Phong.

One thing rises and strikes strongly in Le’s book. With each series created independently of each other, seamed together with one theme, chronologically arranged though not strictly so, one catches the sense of evolution in not just the way Le deals with the subject of war, but also in her presentation of the relation between humans and landscape. From one series to the next, landscapes were not exhibited as props for the human narratives but increasingly as a subject by their own rights.

In ‘Viêt Nam’, nature carpeted the living. Trees moved, leaves blurred, the grass swayed. Nature, side by side with humans, tried to return to life. In ‘Small Wars’, lush forests envelope humans. Nature looms wild. Le recalled, “Working with the Vietnam War reenactors I became fascinated by the significance of the landscape in terms of its strategic meaning. Every hilltop, bend in the road, group of trees and open field became a possibility for an ambush, an escape route, a landing zone, or a campsite.” Nature becomes either an accomplice or an enemy. Finally, in ‘29 Palms’, stillness reigns. Human actions get dropped in the middle of the vastness of nature. We stand from afar looking at tanks crossing a desert. The tanks, as our minds interpret, are sinister weapons of death, yet take just a small portion of the whole picture. The large clouds hovering above and the expanse of the desert are what trap our eyes the most.

As the mind is led to absorb the enormity of nature, it grows to regard the human acts of war senseless. In the larger scheme of things, years or decades later, the mountains will stand there, serene and imposing, the desert will lie there, still and steaming, and large white clouds will keep strolling past the skies. But we, humans, and our wars will be gone. Nature, as ancient organisms who have witnessed our rises and falls, our wars and revolutions, our destructions and renaissances, will remain anchored to existence more firmly than we can ever hope to be.

“Although categorised as a photo-journalistic book, ‘Small Wars’ does not merely document. The photos are not time capsules of what happened.”

Although categorised as a photo-journalistic book, ‘Small Wars’ does not merely document. The photos are not time capsules of what happened. They feel more like evidence of thoughts. Le didn’t make photographs as a way to place a mirror to reflect reality. She placed the photographed reality as a mirror to reflect the mind of her own, and ourselves.

Mai Huyen Chi is a writer and filmmaker. She is a graduate from the London Film School with an MA in Screenwriting and formerly was the Editor-in-chief of MSN Vietnam.

Chi's directorial debut, the short documentary Down The Stream (Thì Sông Cứ Chảy) has earned her a nomination for Vimeo's Best of The Year 2015 and a dozen of other festival awards. Two of her screenplays have been produced in Vietnam (My Mr. Wife) and the United Kingdom (A Brixton Tale).

She is currently working on two independent feature-length narrative projects as a writer/ director: The River Knows Our Names and The Girl from Daklak.