Review of Singapore Biennale

Models of change at NGS and LASALLE sites

By Zulkhairi Zulkiflee

The highly anticipated Singapore Biennale (SB) returns for its sixth edition helmed by art historian-curator Patrick Flores and six other regional curators. Succinctly titled ‘Every Step in the Right Direction’, the biennale gathers 77 artists and artist collectives proposing for a larger scheme of change. Flores sets the tone in his statement for SB2019 where his recollection of Salud Algabre’s words, “each one is a step in the right direction'', highlights the idea that change has to be immediate, if not cumulative in both its successes and failures. This biennale is a timely reflection of what change entails; not in the sense of micro-specificities or macro efforts but one that is made complicated in the current milieu of virtue-signalling and performative activism. Here, hybrid personalities from the past become recurring motifs throughout the exhibition and are summoned as active agents for the present.

Celine Condorelli, ‘Spatial Composition 13’, 2019. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

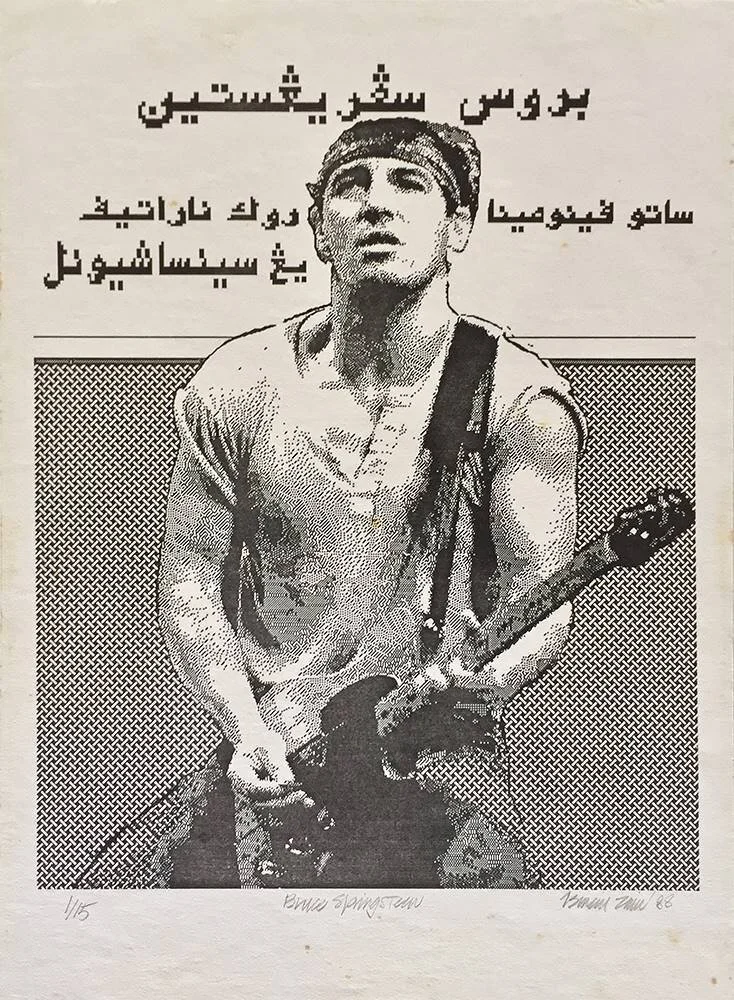

At the National Gallery Singapore (NGS), I am first drawn to London-based artist Celine Condorelli’s ‘Spatial Composition 13’ which sprawls across three galleries. Sprightly, beach-like chairs act as representative structures and also an extension of her iterative project on “support structures”. The artist has considered “support” as the emotional forces between friendships. We see this through the collection of artworks: Raymundo Albano’s staggered line of posters for the Cultural Centre of the Philippines (CCP), Ha Bik Chuen’s modified book frozen at a page of masked individuals, and Ismail Zain’s dot matrix prints of Bruce Springsteen with hovering Jawi scripts amongst others.

Ismail Zain, ‘Bruce Springsteen’, 1988, black-and-white digital print, 25.8 x 20cm, collection of National Gallery Singapore. Image courtesy of National Heritage Board.

In this instance, Condorelli has been elected as a pseudo-curator where she is entrusted with the histories of her Asian counterparts. Her role amplifies her predecessors’ who are historically known to straddle various responsibilities, including curating before its professionalisation. This also spotlights artists as materials in their own right apart from their role as creative workers. In the current landscape of frenzied collaborations amongst creatives, this is an empathetic move from the more familiar strategies of dispersed labour and horizontal working structures.

While Condorelli revises such histories through the relevance of her own curatorial preoccupation, her involvement appears slight based on her artistic repertoire. One wonders whether the “structure” in question could take a more invested shape in scale and complexity. While it is understood that Condorelli’s “structures” are meeting points for the featured artists, the endeavour wants for more.

Exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, ‘Untitled (Theresa’s last work)’, 1983 (detail). Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

We continue to see artists as an interesting point of confluence. In Theresa Hak’s ‘Untitled (Theresa’s last work)’ and Petros Moris’s ‘Nature of Translation (to Theresa)’, acquaintanceship takes enigmatic and generative form. Hak’s black-and-white “(re)photographs” of cropped hands taken from classical paintings are reinterpreted into a set of stark visuals. While the intention behind them remains unshared due to the artist’s passing, it is not difficult to identify a recurring pattern of intra-referencing amongst artists. While Hak referred to the works of European artists through her experimental translation, Moris echoes this by referencing hers.

Petros Moris, ‘Nature of Translation (to Theresa)’, 2019. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

This is manifested through a set of marble works that are placed on the opposite wall. The works take shape as undulating forms marred by intermittent blows of spray paint which are visceral. This “homage” also follows Hak’s book ‘Dictee’ which revisits women in history and mythology. It is worth stating that the curatorial decision here is noteworthy, especially for such an unconventional mediation and pairing. In a podcast episode of Art & Market Conversations, Flores encouraged artists to spend time with works of other artists that are “not kindred”, and we see such sentiments in this curatorial sleight of hand.

Prapat Jiwarangsan, ‘Aesthetics 101’, 2019. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

At LASALLE College of the Arts, another site for SB2019, we are faintly reminded of the dialogues between creatives from the NGS. Prapat Jiwarangsan does this through ‘Aesthetics 101’ where he traces the archive of the late art theorist Somkiat Tangnamo, a prolific figure who initiated the free virtual university called Midnight University. The online resource is an educational tool that offers scholarly articles and a free forum for public discussions. In his work, Jiwarangsan uncovers a separate repository of Tangnamo’s teaching materials of photographic film slides. Originally uncategorised, the artist attempts to create affinities between the slides through pedagogical experiments. The installation acts like a living machine powered by an analogue slide projector and a digital one, ticking wide-ranging visual sources. At the same time, Jiwarangsan places two lightboxes in the area with selected slides and a magnifier for the viewers’ “activation”.

Centro Audiovisual Max Stahl Timor Leste (CAMSTL), ‘Birth (of a Nation)’ (video stills), 2019. Images courtesy of the Artist.

Nearby, the 7-channel video installation 'Birth (of a Nation)' by Centro Audiovisual Max Stahl Timor Leste (CAMSTL) hovers in a black chamber-like corner. We witness archival clips running on their individual rhythms playing disparate scenes of dances, street protests and a breastfeeding mother amongst others. While stylistically offering a fragmented account of Timor Leste’s history through the video installation, they respectively exist as documentation of the country’s daily affairs that are significant in mediating the country’s process to independence.

At the same time that they offer materials beckoning viewers to engage and make sense of them, they risk falling prey to the spectacle of archival display. There are tendencies for such materials to territorialise knowledge production in the hands of power and both artists have clearly appropriated their respective materials beyond such regulatory use. Yet in my view, the work shies away from a clear position or commentary. Should they assert rather than just present?

Mark Sanchez, ‘From Where Labour Blooms’, 2019. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum.

A highlight at LASALLE is ‘The Mamitua Saber Project’, which is distinct and exacting at the same time. The paracuratorial project surrounds the contribution of Dr Mamitua Saber who was instrumental in developing Mindanao’s culture and civic life. The term paracuratorial is significant in this instance. It is an alternative to curating as a form of selecting and staging, focusing on discursive events that are research-driven. In ‘The Mamitua Saber Project’, curating is still the main activity but is nuanced and responsive. Mark Sanchez, Bakudapan Food Study Group and •• PROPAGANDA DEPARTMENT gleans the legacy Dr Saber in varied forms and to compelling use.

Tracing the issues of agriculture on the ground, ‘From Where Labour Blooms’ by Sanchez summons a collection of materials tucked away in folders, and displayed throughout: readings on peasant struggles, photographs of protest actions, portraits of wealthy Filipino class and screen grabs of Google street views awaits invested study. Glass book-stands lay parallel to the corner space where brown carpeted-like floors show diagrammatic arrows.

While the arrangements seemed overwhelming at first glance, the installation reveals the grounded nature of socially-driven practice where inquiry is a collage of everyday sources. For example, a forceful component can be seen through Sanchez’s response to the diagram of the Marginal Leader as illustrated by Saber. He appropriates such material through hand scrawls and bold superimposition of his own quips. Sanchez highlights the tension between the dominant and the marginalized majority by utilising assertive terms such as “perpetuators”, “fatalism” and “imperialism”. Still, his intellectual formulation may confound some.

In contrast, •• PROPAGANDA DEPARTMENT’s ‘Etc., Etc., No. 3: About To, Thereafter’ presents itself as a kinetic installation of stylised wind hose. Appearing more focused in terms of arrangement, the attention is anchored on the contraption, if not dispersed through the chaos of printed matters. An instruction beckons to catch a reading but it is mostly cryptic at interaction. While the work is said to revolve around language and cross-cultural transactions, it loses its communicative thrust as mostly absorbed by the experimental display.

The Bakudapan Food Study Group is last in the team of three and offers a paced respite. We see ‘Moro Moro’ as another iterative study of food as a point of confluence and departure, this time through Morotai’s food culture. In the foreground are artefacts with scent encased in acrylic and lined on the table. Beckoning viewers to take a sniff, the space is also surrounded with a wall work of hand-drawn maps and floras that scaffolds an understanding of Morotai’s food history. On one side, a composition of found plates, pots and cups overhang off the wall, their surfaces treated with glossy, enamel-like paint depicting naive-abstracted characters preparing food.

‘Moro Moro’ by The Bakudapan Food Study Group is the most succinct in contrast to Sanchez and •• PROPAGANDA DEPARTMENT. The work allows for an unpacking that is unhurried and layered through the various components. ‘The Mamitua Saber Project’ is wholesome for its diverse offer, ranging in artistic display and level of research. Beyond the project, I am urged to think of a similar project based on significant figures in Singapore. Who would be an equivalent?

This biennale may have reoriented the nature of experiencing art; it is calculated and transparent in its agenda. It is empathetic to people as forces and sometimes, openly chooses who to side. Yet on the flipside, while we know change is urgent and bears gravity that brings to mind affirmative action or even fortification, the SB2019 gathers propositions from history through personalities and agents of change. Witnessing change through these role models is a critical source for influencing one’s self-efficacy. This enables continuous change and renewal.

Read our first story on the SB2019 here.

Listen to our A&M Conversations with SB2019 Artistic Director Patrick Flores here.

A&M is proud to be an official media partner of the SB2019, which runs from 22 November 2019 to 22 March 2020 at various locations. For more information, visit singaporebiennale.org.