Conversation with Roger Nelson

Trans-media intersections, vernacular methodologies and "curating as art history"

By Ian Tee

Roger Nelson.

Roger Nelson is an art historian and curator. His research approaches modern and contemporary arts of Southeast Asia from interdisciplinary perspectives, with a focus on Cambodia and Laos as points of intersection. He was a participating scholar in 'Ambitious Alignments: New Histories of Southeast Asian Art' funded by the Getty Foundation, and a research fellow at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (NTU CCA). In 2019, Roger joined the National Gallery Singapore (NGS) as curator.

In this interview, we hear about his early curatorial projects, insights on Cambodian history and thoughts on the "modern" and "contemporary" as concepts in Southeast Asian art.

Roger Nelson installing Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan’s artwork for the exhibition 'new artefacts' at SA SA BASSAC, Phnom Penh, 2012. Photo by Lim Sokchanlina.

I'd like to begin this interview with early curatorial experiences. You were the founding director of No No Gallery in Melbourne, Australia, from 2010 to 2012. It was a not-for-profit exhibition space showcasing contemporary art. What did you gain or learn from that role that has stayed with you? How did you end up in Phnom Penh?

Much of my curatorial work, especially with living artists, has been guided by attempts at experimentation, long-term intellectual exchanges with artists, and a desire for playfulness. In hindsight, this was already my mode of working since the days of No No Gallery, and other DIY pop-up exhibitions organised with friends at various warehouse spaces in Melbourne in the late 2000s. They were done for fun, with no money and zero “proper” infrastructure, functioning mostly through word of mouth. These shows were mostly just an excuse to take risks, try things out, and to have long conversations with artists. But they were also a lot of hard work. I ran No No Gallery while working full-time in the Asia Institute at the University of Melbourne. Many Sundays were spent repainting the walls, and many exhibition press releases were written during lunch break on campus.

One of the first exhibitions I curated in Phnom Penh was 'new artefacts' at SA SA BASSAC in 2012. It announced itself to be “experimentally exploring process: in the practice of contemporary artists, and also as a mode of documentation and exhibition.” The show consisted of artists’ working materials salvaged from studios and storage rooms, as well as notes, sketches, and works that had been “edited out” of larger series. But most crucially, for me, it provided an opportunity to deepen and focus my conversations with the artists, many of whom I have continued to work with, be friends with, and learn from in the years since.

Khvay Samnang, one of the artists from the show, told me the following year that “if you want to know, you have to come, and not just talk, but enjoy! And spend time, not just one hour or one day.” I think Samnang was already growing weary of curators who visited him in Phnom Penh for a single, short trip which often counted as their primary “research". I respect his desire to find playful ways to form a more sustained connection with his collaborators, including with curators.

I’d been visiting Cambodia over the course of several years, slowly and carefully trying to navigate a path toward doing research there, shaping questions to guide my growing curiosity about the country’s art history and its place in the art history of the region. I eventually moved to Phnom Penh for an Asialink curatorial residency, and just stayed on when it ended. By then I was already studying Khmer, and learning a great many other things too. I started the research that eventually informed my PhD on the modern and contemporary art of Cambodia. It was largely done in archives, but what I learned through that solitary process of poring over old documents was very much animated and made sense of over long dinners with artists, curators, architects, dancers, filmmakers, and other researchers.

Pinaree Sanpitak’s 'Breast Stupa Cookery Project: Prahok/Plaa Raa', Phsar Kap Ko restaurant, Phnom Penh, 2014. Presented as part of ‘Rates of Exchange, Un-Compared.’ Photo by Khvay Samnang.

‘Rates of Exchange, Un-Compared’ (2014-15) was an ambitious six-month-long project of exhibitions, residencies and public programmes, which you co-curated with Brian Curtin. Could you talk about the curatorial and practical considerations that went into this format? How did the two of you pull together resources to realise the project?

This project was much more experimental in its conception and its format. As I remember, it was driven by curiosity about three matters, as viewed from our positions in Bangkok and in Phnom Penh.

First, how could we as curators facilitate Bangkok and Phnom Penh-based artists’ interactions with each other and with various publics, but while imposing as slight a curatorial framework as possible in order to try to avoid predetermining the nature and outcomes of those exchanges? For me, this question was in part a reaction against a growing tendency within contemporary curatorial practice towards grandiose group exhibitions on a vast scale, in which the curator’s ideas are sometimes felt more loudly than those of the artists. Perhaps it’s just a personal preference, but I often feel unsatisfied by those kinds of exhibitions, and I also wonder if there mightn’t be something at times almost colonial about the imposition of a curatorial logic over very diverse artistic practices. To put it another way, we devised 'Rates of Exchange, Un-Compared' not so that we as curators could say something with the project, but instead in hopes that it would enable artists to say something, especially to each other.

Second, we wanted to see how the various apparatuses of residencies, talks and symposia, group exhibitions, workshops, performances, as well as more informal kinds of gatherings might inform each other. At that time, artists and audiences in these two cities had very little exchange, so we also wanted to find out which formats would have a deeper and more lasting impact on them. In the end, the programme actually extended beyond the six months we had initially planned, and expanded beyond Bangkok and Phnom Penh. In addition to the venues originally envisaged, we also managed to facilitate Phnom Penh-based artist Lim Sokchanlina's residency in Chiang Mai, as well as arranged a display of Pen Sereypagna's 'Phnom Penh Visions' project at Art Stage Singapore 2015, where artist Orawan Arunrak and others also participated in a panel discussion.

Third, we wanted to see how far we could stretch a grant from the Australia Council of the Arts, through the generosity and goodwill of participating artists and venues we worked with. There’s such a radical asymmetry in the way money is used in the arts across different parts of Southeast Asia. In retrospect, it is still quite a surprise that we were able to facilitate so much movement and exchange with only around SGD10,000.

There were some beautiful moments in this project. One delicious memory is eating different dishes prepared with the fermented fish paste, called prahok in Khmer and plaa raa in Thai. They were served in the unique vessels provided by artist Pinaree Sanpitak, as part of her ongoing 'Breast Stupa Cookery Project'. That festive event was held at a local restaurant frequented by artists in Phnom Penh’s Phsar Kap Ko neighbourhood, which is sadly now gone as one of countless victims of the city’s lightning-speed construction.

However, the most rewarding aspects of this project were the long-term friendships and collaborations that it facilitated, both among the invited participants and others who took part in less formal capacities. For example, Tada Hengsapkul and Orawan Arunrak from Bangkok both made important works during their return visits to Phnom Penh. Many younger artists in Cambodia who joined as audience members have gone on to form their own dialogues with artists in Thailand. There is now a great deal more exchange between the arts communities in Phnom Penh and Bangkok, and for that I feel thankful.

'People, Money, Ghosts (Movement as Metaphor)', 2017, exhibition installation view at Jim Thompson Art Centre. Works by (from left: Nguyen Thi Thanh Mai, Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, Khvay Samnang. Photo by Lim Sokchanlina.

Nikos Papastergiadis' definition of "deterritorialisation" was a key influence in your 2017 exhibition 'People, Money, Ghosts (Movement as Metaphor)' at Jim Thompson Art Centre. In what way does Papastergiadis' definition differ from other claims on this concept? And how did his idea play out in your curatorial approach to this exhibition?

With this exhibition, as with most of my curatorial work, the guiding ideas really came from the practices of the participating artists. I wrote in the exhibition's introductory text that it “begins from the observation that many contemporary artists are embracing travel and movement as necessary conditions for practice.” I chose to work with Khvay Samnang, Nguyen Thi Thanh Mai, and the collaborating artists Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho because I’ve had the privilege of watching their work unfold along these flight-lines. Mai’s project in the Jim Thompson Art Centre show, for example, was actually its fourth iteration, coming after our previous collaborations for shows in Phnom Penh, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi. Through conversations with all of these artists, among others, I came to the articulation that “mobility becomes a methodology of research, and also a rich site of inquiry in itself.”

Nikos Papastergiadis’ writing on “deterritorialisation” was one of a handful of texts I discussed in the exhibition catalogue, alongside publications as diverse as Ananda Coomaraswamy’s essay 'Intellectual Fraternity' which in 1918 was already describing “a world of rapid communications”; Geeta Kapur’s account of tendencies in Southeast Asia’s contemporary art during the 1990s; Robert Musil’s nightmarish account of the “spectral aspect” of technological modernity; and even an untranslated Khmer introduction to Cambodian culture, in which the author, Neak Srei Troeung Ngea, emphasises the nimble integration of “foreign influences” even during the premodern and early modern periods.

Nikos was one of my doctoral supervisors, so again my engagement with his thinking had been unfolding over a number of years. I was drawn to his approach to the very widely-theorised concept of deterritorialisation because it enables a multiplicity of overlapping affiliations. He observes that “people now feel they belong to various communities” despite being geographically dispersed, and that this enables “a more dynamic relationship between past and present.”

Importantly, Nikos contends that for artists a “nomadic sensibility is not necessarily a rootless existence.” This resonates very clearly with how the artists in the show articulated their experience. For example, since they began working as a duo in 2009, Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho have never had a stable home base from which they practise, instead collaborating long-distance, or travelling in order to make their work.

'And in the Chapel and in the Temples: research in progress by Buddhist Archive of Photography and Army Lien and Enzo Camacho', 2018-19, installation view at NTU CCA, Singapore. Image courtesy of NTU CCA Singapore.

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho were also involved in 'And in the Chapel and in the Temples' (2018-19) at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore. Their presentation focused on Alfonso Ossorio, a queer Filipino-American modernist painter, whose work is featured in the 2019 Singapore Biennale. What was the dialogue you wanted to generate with Lien and Camacho?

It was such a privilege to be able to present Amy and Enzo’s work on Ossorio for the first time, as this is a vein of inquiry that they had been researching for a number of years. We went on a memorable trip to visit Ossorio’s famous 'Angry Christ' mural in Victorias City together, during which his maniacally mannered style began to make a different kind of sense after we were given behind-the-scenes tours of the sugar mill next door as well as some of the plantations in the area.

What most exhilarates me about Amy and Enzo’s approach to Ossorio is that it makes manifest what Nikos calls a “dynamic relationship between past and present.” For Amy and Enzo, the story of Ossorio is like a magical portal, and through it, they can approach a dazzling array of other questions. They range from colonial and postcolonial Philippine (art) histories, to contemporary economic mechanisms of subjugation, via queer and archipelagic sensibilities and exhibitionary strategies, and a whole array of other concerns in between. I see Amy and Enzo using Ossorio's story like a prism, through which these various matters are refracted and bleed into one another.

I was really fortunate that NTU CCA Singapore generously gave me the opportunity to present some of this work, and to curatorially juxtapose it with another fascinating body of images from quite a different context: photographs taken and collected by monks, from the Buddhist Archive of Photography in Luang Prabang.

Roger Nelson and Singaporean artist Hilmi Johandi in his studio. Photo by Andrea Fam.

My next question has to do with the relationship between curators and young artists, especially as it pertains to the development of new works or commissions. One example in which this plays out more formally is your involvement in the Singapore Art Museum's 'President’s Young Talents 2018' as a co-curator and mentor to the artist Hilmi Johandi. What roles do you play and are there boundaries you draw?

Each edition of the ‘President’s Young Talents’ has been organised in a different way. I was lucky enough to be part of a team of independent curators and artists invited to nominate the participating artists and work very closely with them on their commissioned project. SAM was there to guide the process, but we were given a surprising and very generous degree of autonomy.

The term “mentor” always felt a bit odd to me. Whenever I was introduced as Hilmi’s mentor, I’d always counter that I felt I was learning much more from him than he was from me! Hilmi is an artist I’ve admired since first encountering his work in 2013 when I was invited to be one of the judges for the exciting but short-lived Spot Art exhibition, and then seeing his extraordinary first solo exhibition in 2014.

I had a great time having long, meandering conversations with Hilmi, and we asked each other challenging questions. Some of these had to deal with the archival materials he was citing, appropriating, and refunctioning in his work, which related to the early post-independence period that much of my research also considers. We also discussed his approach to materials and form, his desire to do more than painting, and yet still have the medium and the pleasure he finds in it somehow inform his broader practice.

With Hilmi, as with any artist I work with, I would listen and ask questions. Sometimes, I would also offer observations which are based on having had the privilege of looking closely at their work. However, I guess where I draw the line in this kind of process is at making too many specific suggestions about the work. I know some curators who see their role as shaping the work, in collaboration with an artist. But for me, the ideas should come from the artist.

This kind of collaboration informs my approach to historical art, just as any research on art history often adds fuel to conversations with living artists. It’s a process that Hilmi very elegantly describes in my interview with him for the President’s Young Talents catalogue as “a kind of alchemy” and “a constant sway".

Cover of 'A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land', a novel by Suon Sorin translated by Roger Nelson. Published by National University of Singapore Press (2019).

Most recently, you translated Suon Sorin's novel 'A New Sun Rises over the Old Land' from Khmer to English. First published in 1961, the work is an iconic piece of modern Khmer literature that offers insight into the period between Cambodia's independence from French colonial rule and the Khmer Rouge atrocities of the 1970s. When did you first come across this novel? What were your motivations for embarking on this project?

Ideas come from artists, but of course artists don’t work in a vacuum. In almost every Southeast Asian language, as in English, the term used to refer to “art” can describe not only visual art or fine art, but the arts in a wide variety of media. The work that artists do is always engaged with other cultural forms, in a process that I call trans-media intersections. I find this aspect of the history of modern art in Southeast Asia is under-explored. For me, these trans-media intersections are quite thrilling and illuminating, as they reveal something about the position and function of art in relation to the wider culture of its day, and about the reception of art in the context and moment in which it’s made.

Translating Suon Sorin’s canonical novel was motivated by my desire to find a means, and also a vocabulary, for making sense of paintings made in Cambodia in the 1960s. When Sorin enthused that post-independence Phnom Penh was like “the face of the nation,” or rhapsodised that “the Khmer rice fields were like gold and jewels, for a flourishing economy,” this resonates in very special ways with the work that was being made at the time by the leading artists in Cambodia. They include individuals such as Sam Yoeun, whose work is now on display at NGS, and Nhek Dim whose work will also be going on display later this year.

Although this was my own specific interest in translating the novel, I also think Sorin’s writing offers other kinds of valuable insight into that period. It was a moment of relative, though in hindsight quite deceptive, calm between the end of colonial rule, and the beginning of civil war. I relish reading literature translated from Southeast Asian languages, and was shocked to realise that no Khmer novels from this period were available in English. So much of the writing in English about Cambodia centres either on its pre-modern glories, or on the country’s suffering under Pol Pot. Yet so many of the young Cambodians I know insist on telling different kinds of stories, and showing other sides to the nation’s history and present.

I hope that by making Suon Sorin’s novel available in English, it might be one more primary source on Cambodia that might enable other interests and inquiries in the future, be it for research or recreation. In a 1963 Khmer pedagogical text I quoted in the novel’s introduction, the literary scholar Khuon Sokhamphu writes that “whatever we study about literature, we will study about people.” This has substantially informed my thinking about this novel, and about vernacular, de-imperialised methodologies for approaching literature and the arts more broadly.

Staying on the topic of translation, I think it is noteworthy to bring up 'Terminologies of "Modern" and "Contemporary" "Art" in Southeast Asia's Vernacular Languages' (2018). Your contribution concludes with the bold claim: "What is striking about the Khmer case, however, is that the word samay is used to refer to either the modern or the contemporary—or both—not only by laypeople, but also by artists, writers and those most specifically invested in art-related discourse. This also means that to regard either the modern or the contemporary as a discrete or distinct era (in history or in art) is nonsensical in Khmer, linguistically and therefore also conceptually."

How has this insight informed your approach/ perception towards art from the region since? Were there any interesting responses to your article?

You’re quoting from my short text on the terms “modern,” “contemporary” and “art” in Khmer, which is part of a huge, collaborative effort with 10 authors looking at these terms in nine different Southeast Asian languages. The article, which is free to read or download, was a lot of work to put together, but for me has been incredibly useful as an aid for more thinking and research. It’s also the most-read article that the journal has published so far, attracting more than a thousand downloads within the first few weeks. I hope that in time this might lead to critical responses to these ideas being published.

In making that argument about the Khmer terminology of the “modern” and the “contemporary”, I was proposing that the modern and the contemporary can now only exist as concepts in relation to each other. I choose the word “concepts” rather than “periods” quite deliberately. I don’t see the modern as a moment that has passed and been replaced by the contemporary, but rather I see the two as co-extensive ideas that animate each other. We cannot look to the modern without our view of it being grounded in the contemporary. Equally, we cannot make sense of the contemporary without looking to its roots in the modern. Here, I am not referring to a singular Western conception of modernity. Rather, I am pointing to the many locally specific articulations of modernities that have been forged as much through exchanges within Southeast Asia as by interactions across longer distances with other parts of the world.

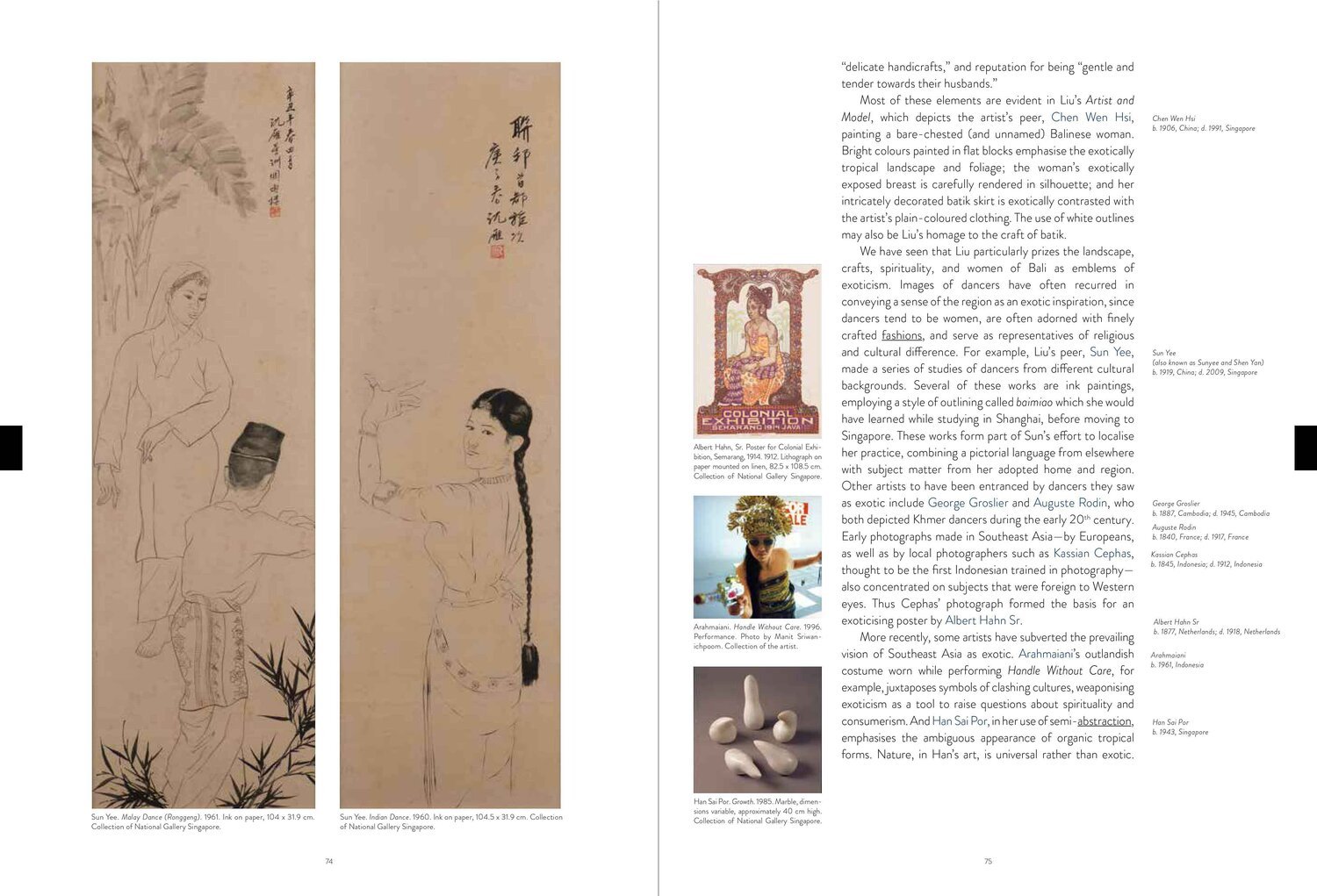

Page spread from 'Modern Art of Southeast Asia: Introductions from A to Z'. Images reproduced with the permission of National Gallery Singapore.

Speaking about another book of yours, could you share how 'Modern Art from Southeast Asia: Introductions from A to Z' came about? The question of its target audience is a salient one as the publication aims to offer "an informative first encounter with art". I am also thinking of this in relation to 'Southeast of Now', a journal which you co-founded.

This book is intended for a general reader, or someone without any special involvement in art. This makes it different from most of what I write and from 'Southeast of Now' which is usually addressed to a specialist kind of reader. So writing 'A to Z' caused me an embarrassing amount of anxiety because nothing quite like this has existed before. There are entry-level books on modern art of the West, and on the pre-modern art of Southeast Asia, but there had not yet been a book that tries to introduce the modern art of this region in an inviting, accessible way.

I received an invitation to write this book from NGS when I was doing my postdoc at NTU, and most of the writing was done before I joined NGS as a curator at the beginning of 2019. The proposed format of the book immediately intrigued me. I saw this as an opportunity to write an introductory volume that wasn’t singular or linear, but instead could be read in any sequence, entered at any point. In the end, the book covers 60 key terms and ideas, ranging from asking who an “artist” is, to the nuances of “social realism,” to thinking expansively about the different ways in which the “quotidian” appears in modern art. It’s not intended to be read from front to back.

I feel quietly pleased with the breadth that we managed to cover in the book, discussing over 200 artists, and striking what I think is a happy balance in terms of geographies and time periods, as well as showcasing works from both public and private collections around the region and beyond. Importantly, around a quarter of the artists I discussed are identified as women, which marks a big increase on most surveys, even though it is still a small percentage.

That said, I do worry that in focusing so much on achieving this breadth and balance, the book necessarily sacrifices the kinds of in-depth discussions that I often value most as a writer and reader. I hope the book is followed by others which offer introductions to the modern art of this region in different ways, with different emphases. I see it as a beginning, not as an end. I also hope that from its breadth, some readers will find their own paths into deeper and perhaps more sustained inquiries. I am encouraged and humbled to know that it’s already being used as a teaching text by art history professors I admire in Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur.

In 'Introductions from A to Z', you wrote that: "Much art historical research and writing in the region has instead been occasioned by exhibitions, which are usually temporary in nature. It may be that a canon of southeast Asian contemporary art from the late 20th and early 21st centuries could be more readily accepted than a canon of modern art of the 19th and 20th centuries." What do you think are the implications of this observation? And how does it relate to or complicate your work at NGS?

Among my colleagues at the Gallery, as among specialist art historians and curators elsewhere, I think we have settled on a number of key artists and artworks from across the 19th and 20th centuries which we can agree are of pivotal importance to the history of art in Southeast Asia. Figures such as Juan Luna, S. Sudjojono, Georgette Chen, Redza Piyadasa, and Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, for example, crop up repeatedly in almost every discussion surveying the art of this region.

But despite this, I still insist that there isn’t yet a canon of modern art in Southeast Asia. Artists who are household names in one country are often almost completely unknown in other places, and I think it’s also worth remembering that it’s only relatively recently that artists like those mentioned above came to be widely discussed by scholars from across the region. Some of these are ideas that I address in a roundtable on the teaching of Southeast Asia’s art histories, which will be published soon in ‘Southeast of Now,’ and will also be free to read or download.

For me, this presents an incredibly exciting opportunity. It means that there isn’t a fixed and stale old story about modern art that we are arguing against or fighting to revise, as there is in many other parts of the world. Instead, there is space here for a multiplicity of different narratives, including divergent and even competing narratives, and ones that imaginatively connect this region with diverse other geographies and imaginaries. I see my work at the Gallery as being largely about looking into the possibilities for the best and sometimes the more unexpected ways to tell often new and always important stories about the rich diversity of the modern art of this region, and its place in the world.

I find it very inspiring that people are taking up this challenging opportunity in a huge variety of different ways in other parts of Southeast Asia, as well, including outside of well-funded state institutions. I have an article coming out soon in ARTMargins, a journal at MIT Press, which describes what I call “curating as art history”. It looks at independent curatorial projects in Ho Chi Minh City, Luang Prabang, and Phnom Penh that operate on a very small budget and without state support. In the essay, I argue that these kinds of projects represent a growing tendency for various kinds of practitioners in the region to conduct and share art historical research through various forms of curatorial practice. This kind of “curating as art history” in Southeast Asia deliberately and self-consciously makes research about the art of the past relevant to the perceived needs of specific communities in the present day. It also insists on an open and expansive approach to art history, seeing it to encompass not only fine art, but also many forms of cultural production, including architecture, amateur photography, and so on. And it does so generously, including by making good use of the possibilities of the digital realm. These kinds of small-scale, independent projects continue to be a rich inspiration.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Read Ian Tee's review of 'Modern Art of Southeast Asia: Introductions from A to Z' here.