Conversation with Curator Syed Muhammad Hafiz

Malay representation in Singapore art history

By Ian Tee

Hafiz with artist Iskandar Jalil at a multi-chambered noborigama (step-up kiln) located within the compound of the Kawai Kenjiro House in Kyoto, December 2015. Image courtesy of Syed Muhammad Hafiz.

Syed Muhammad Hafiz is an independent Singaporean curator interested in the sociopolitical histories of the Nusantara, a term loosely translated to mean the "Malay world". Previously, he was assistant curator with National Gallery Singapore (NGS), where he co-curated the Southeast Asia permanent exhibition 'Between Declarations and Dreams', as well as 'Iskandar Jalil: Kembara Tanah Liat (Clay Travels)' and 'Between Worlds: Raden Saleh and Juan Luna'. Recent projects in Malaysia include curating the solo shows by Ahmad Fuad Osman for A+ Works of Art, and Ahmad Shukri Mohamed for Segaris Art Centre.

In this interview, Hafiz shares his journey as a curator, his thoughts on Malay representation in Singapore art history and his latest exhibition on Jaafar Latiff, a forgotten Singapore modernist.

Jaafar Latiff, 'Wandering Wonder 3/78', 1978, mixed media on canvas, 108 x 207cm. Collection of the artist's family.

I'd like to begin this conversation by discussing your essay on Artsequator about permanent exhibitions in the NGS. You concluded the piece by saying: "Rather than the anxieties or aspirations to connect the Singapore art story to a global narrative, I think we should start looking more to our archipelagic neighbours."

Could you elaborate on the concept of Nusantara? And what are the implications of adopting a more archipelagic outlook on Singapore and Southeast Asian art history?

Linguistically, Nusantara means different things to different sections of the Nusantara itself. An Indonesian will have a different opinion, compared to a Malaysian or someone from Brunei. However, I look at Singapore's art history through this framework. There is the prevalent 'Nanyang' worldview and the 'Nusantara' worldview offers another perspective if one is to look at our history over the last 100 years. This was the topic of my Masters thesis at Goldsmiths, which I wrote 10 years ago.

The idea of Southeast Asia or ASEAN is another interesting framework to study for art history, which revolves around nation-states with all the associated political entanglements. There have been many recent seminars or symposiums centred around the post-Cold War period. But I guess I’m adopting a more inward approach. I think there is much to be studied and comparisons to be made when one looks inwards and moves laterally across the archipelago. Recently, I’ve been reading a lot about the Martinique writer and poet Édouard Glissant whom I came across in one of Han-Ulrich Obrist’s interviews. It’s been a riveting journey and I keep coming back to the idea of archipelagoes as a way of studying culture.

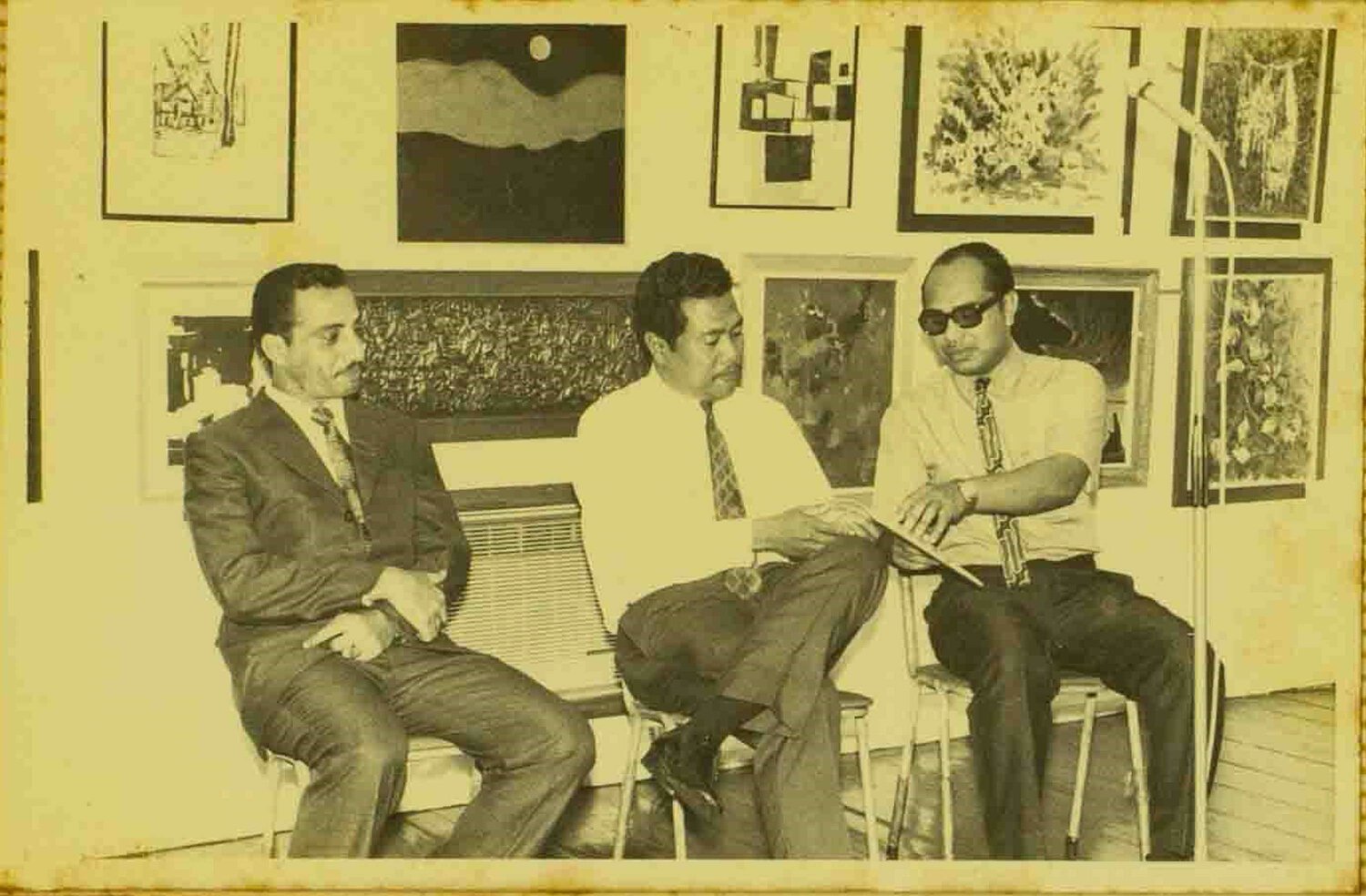

Archival image from 1971. Left to right: Hussain Aljunied (Founder of Malay Art Gallery), Mr Sha'ari Tadin (Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Culture) and Abdul Ghani Hamid (Co-Founder of APAD) officiating a group exhibition of Malay artists in 1971 at the Malay Art Gallery. Image courtesy of Hussain Aljuined’s family.

Probing deeper into the impetus for that article, what are the reasons why Malay artists are under-represented in the Singapore art story?

Maybe you can wait for my thesis to be completed in 2 years’ time? (laughs) That’s the reason why I’m doing my PhD! I can give you a list of reasons but generally, I think it’s not an issue of numbers. Instead, it has more to do with the way Singapore art history has been written. This has an impact on how the discipline is studied and perceived, at least in the local context. There is a similar problem at the global level too which is why you’re starting to see many more exhibitions on black artists, queer artists, female artists, etc.

Recently, there are attempts to "decolonise" language but to be honest, I am not sure about that too. We are all implicated one way or another, so is it ever possible to "decolonise" ourselves? I think the only way forward is to acknowledge differences meaningfully and to understand the value of diversity.

Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya, or APAD, is an important art society for Malay artists established in 1962 which remains active till this day. How did racial dynamics influence the Malayan art scene during the 1940s to 1960s? And what role do you see APAD playing today?

This is a tough question which could be a thesis by itself! For a start, APAD was important to the Malay artists then because it was one of the few, or perhaps even the only platform for them to exhibit. More importantly, APAD provided peer support and art lessons for those who couldn’t afford to go to an art academy, such as the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. We have to remember that in those days, the idea of going to an art school was already challenging for most people. I came across more than a few interviews with Malay artists who said that it was too expensive for them to study at the academies so they went to APAD for affordable classes taught by the Malay senior artists.

APAD was like the ‘sanggar’ (studio) in Indonesia where masters such as S. Sudjojono and Hendra Gunawan operated and became mentors to younger artists. In today's context, I don’t think APAD serves that function anymore. The problem of recruiting younger members is one faced by all surviving art societies in Singapore, not just APAD. Perhaps, the landscape has changed where artists don’t need that type of support system. Having said that, I think APAD still has a role to play but its younger members need to know about the society’s historical significance. They also need to plan more shows that are properly curated and documented in catalogues. This is my perspective as a non-member.

‘Iskandar Jalil: Kembara Tanah Liat (Clay Travels)’, Gallery 2 featuring Gerald Leow’s installation ‘Some of you may be asked to leave’ alongside works from the artist’s family collection.

During your time at NGS, you co-curated 'Iskandar Jalil: Kembara Tanah Liat (Clay Travels)'. It was the artist's first major survey exhibition, occupying two galleries on the museum's concourse level. In one of them, contemporary Singaporean artist Gerald Leow was commissioned to produce an artwork in response to Iskandar's ceramic works. Could you talk about that room and how are the two artists connected?

The two artists had never met. When I was tasked to co-curate the show, I thought how I could engage a younger, contemporary audience with an artist whose works spans five decades. How might I sustain the interest of the viewers to an exhibition filled with more than 100 pieces of clay pots and vessels? My decision was to bring on board an artist who is not only much younger than Iskandar Jalil, but also someone who has the temperament and tenacity to work on this collaboration. Of course, it helped that I had known Gerald Leow for quite some time. I’ve always been interested in his research-based practice and the sculptural elements in his works.

I had a gut feeling that they would click, and they did through the course of our research trip to Japan together, leading up to the exhibition! My only brief to Gerald was to get to know ‘Cikgu Iskandar’, or Teacher Iskandar, better and see what could come out of that. The room was the result of their conversation. I played a very minimal role in the process, only facilitating the execution of Gerald’s work which was titled ‘Some of you may be asked to leave’.

The artwork was the house structure loosely inspired by Iskandar’s very first studio environment, his parent’s traditional house in a kampong in the eastern part of Singapore. The title was based on a note that Iskandar usually pinned on the door of his classroom. Some of his students would have seen it, especially if they had been late to class or been thrown out of his classes!

Hafiz with his classmates from the MA Art & Politics program (Goldsmiths College) at Manifesta 8 in Murcia, Spain in December 2010. Image courtesy of Syed Muhammad Hafiz.

My next question brings us back to the beginning. You completed your undergraduate degree at LASALLE College of the Arts. Did you intend to be a curator from the get-go? How did you get your foot in the door?

When I enrolled as an Arts Management student in LASALLE, I made it a point to try everything during my first year. I became a stagehand and worked for a music festival, for example. I enjoyed all those experiences but none of them excited me as much as my internship at SAM in 2008. Before that, I already had some interest in attending exhibitions and was doing odd jobs for galleries, such as installing and de-installing shows. I was paid $50 a day for those gigs, which was a lot for me as a student then!

Amongst one of the freelance jobs was writing for the Singapore Art Gallery Guide (SAGG). The publication is still around but I think it is more known for providing listings today. Back then, SAGG had a better editorial team and paid for articles, so I was going around town doing previews or reviews of exhibitions. This made me learn more about the local visual arts landscape. Of course, the most fun part was hanging out with artists and getting to know more about their works!

If you’re asking how I got my foot in the door, I think it must have been the internship at SAM because they gave me my first job upon graduation from LASALLE in 2009. The various odd jobs made me understand what being a curator meant while my time as a researcher at SAM confirmed my decision to pursue this career. That was why I left after a year to complete a graduate degree at Goldsmiths, with the intention to return and work as a curator at an institution in Singapore.

Thus far, you've worked on exhibitions in different capacities, from institutional positions at SAM and NGS, to freelance projects with commercial galleries such as A+ Works of Art and other organisations. Are there any skills or lessons learnt that remain particularly helpful?

There are too many to list! But if there's one, it must be empathy, the ability to understand, and more importantly, listen. Whether it’s listening to artists, the public — which is the hardest — or simply people whom one works with. I think this is the most mentally taxing part of being a curator. The way you process all that information will shape the kind of curator you become, and these lessons can only come from experience.

The arts industry is all about working with people. Yes, one might be a brilliant writer or sell a lot of artworks. But what is the point if one can’t listen with empathy? Then it just becomes another job when we could be building meaningful relationships and learning from each other.

If I may add, the other important quality is humility, which I think is lacking here. We might have a lot going on, with strong government support and infrastructure compared to our neighbours, but I’ve had people telling me it feels "clinical" or everything here seems "very efficient". I might be wrong, but I think it’s down to humility and empathy.

Hilmi Johandi, ‘Painting Archives’, 2019-2020, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Syed Muhammad Hafiz.

Staying on the topic of process, you recently worked with Singaporean artist Hilmi Johandi on 'Painting Archives' at Galeri Rumah Lukis. What were the conversations you had with Hilmi? And how did they relate to the approach taken for displaying his works and research?

I have known Hilmi since our student days at LASALLE and have always seen him as a strong painter. In many ways, I respect his commitment to the genre especially in the Singapore context where I think multidisciplinary artists are privileged.

Rumah Lukis is a contemporary art space in Kuala Lumpur with a focus on exhibiting processes and they invited me to propose a young artist for this project. Hilmi came to my mind as he thrives in the research and development of his paintings. More importantly, I thought it might be interesting to see how the Malaysian audience would react to a Singaporean painter since many young artists in the city begin as painters. This is also Hilmi's first exhibition in Kuala Lumpur.

The exhibition is a presentation of our year-long conversation in a visual format. It features supporting materials to Hilmi's painting practice, such as drawings, sketches, notes and stop-motion video works. Mr Pital, the architect who owns Rumah Lukis, was more than happy to sit back and let us take over his space. This has definitely been one of my most satisfying projects!

The scope of your projects seem to be focused on the modern era. Are there other contemporary artists whom you work with? And what aspect of their work compels you?

Yes, I have to admit until I left NGS two years ago, I was more involved working with artists from the modern era. It was my point of entry as an art history student and the focus I was tasked with as an institutional curator. I’m still researching that period, especially for my PhD. However, since becoming an independent curator, I’ve been more involved with younger artists. Working on ‘Painting Archives’ with Hilmi Johandi was a start. I have also curated a solo show of emerging artist, Syed Fakaruddin, in Malaysia with Segaris Art Centre last year.

I think it has less to do with the kind of work they're making but more about what I can learn from them. With modern artists, you’re mostly working with archives or through family members of those who have passed on. However, with younger artists, I’ve been enjoying the direct conversations with them. They certainly make me feel older! (laughs)

‘Jaafar Latiff: Beyond the Familiar’, 2020, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Syed Muhammad Hafiz.

Your latest project is a survey exhibition of works by the late Jaafar Latiff. Could you talk about the show's title 'Beyond the Familiar'? And what do you hope viewers take away from it?

‘Beyond the Familiar’ is taken from one of the artist’s quotes about a particular series of works he produced. In many ways, Jaafar Latiff’s life and works had that spirit. For example, he is known for his batik paintings which are familiar to us but the way he pushed the medium has garnered some criticisms in the past. To me, Jaafar Latiff was always pushing boundaries and testing limits. His son, who invited me to work with the family collection for this exhibition, mentioned his dad would be "a disruptor of sorts" in today’s context!

From the beginning of this project, I have been intrigued by Jaafar Latiff's energy and reputation. He had an almost methodical way of working, which is evident in his attitude towards batik and abstraction. The man also played a significant role in the arts education landscape here. I think he is Singapore’s forgotten modernist. His works are very poorly represented in the market as compared to his second-generation Singaporean peers such as Thomas Yeo, Anthony Poon and Goh Beng Kwan. There could be more research and acknowledgement of his legacies.

Are there other projects you'd like to share?

I’m currently planning the first solo show of Khairulddin Wahab. He was the Singaporean winner of UOB Painting of the Year in 2018. There are also a few group shows that would be happening in Malaysia, Indonesia or Singapore. For now, I will just take my ideas wherever it can be realised in the least "painful" way!

'Jaafar Latiff: Beyond the Familiar' is on view at Artspace @ Helutrans from 8 to 19 January 2020.

'Painting Archives' by Hilmi Johandi is on show at Galeri Rumah Lukis, till February 2020.