Art x Business: Molly Steiger

On the growing and changing market for prints

Molly Steiger is Senior Vice President, Head of Department for Prints and Multiples at Sotheby’s. Steiger is a specialist with nearly three decades of experience in the medium of print, overseeing biannual dedicated Prints & Multiples auctions. She also led the incorporation of prints into Modern & Contemporary Art sales, establishing records for works such as an Andy Warhol Endangered Species portfolio, a complete collection of David Hockney’s Thirty-Three Homemade Prints and a monumental Jasper Johns crosshatch monotype.

We speak to Steiger ahead of her participation in the STPI Symposium 2026: The Politics of Print. In this conversation, she shares insights into the shifting market for print works across time periods, geographies, and collector demographics.

Molly Steiger and Mary Bartow bid spotting, James Niven auctioneering, circa 2005.

You joined Sotheby’s nearly three decades ago in 1997, could you briefly share one or two major turning points in your career?

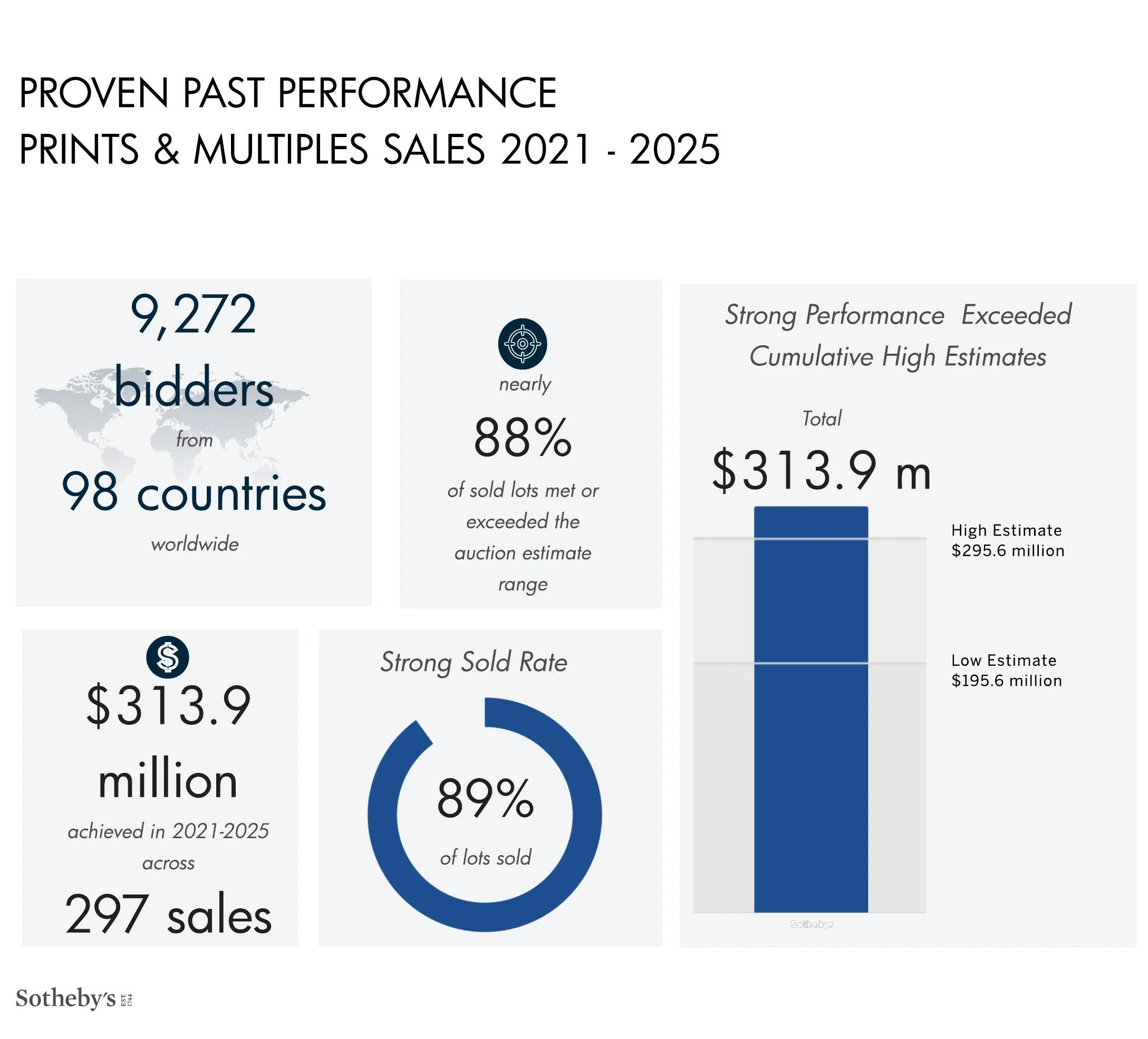

The most noteworthy change in the market has been the embracing of technology. Where we once held live auctions with a person in a podium standing at the front of the room, our sales can now be conducted entirely online and continue to be nearly 90% sold. Our clients are comfortable relying on our expertise, often via email, examining conditions through digital photos, placing bids online and spending well into the six figures. This shift may have been somewhat gradual, but the real turning point was the COVID-19 pandemic, during which Sotheby’s continued to do business, but like the rest of the world, needed to figure out a way to do so online.

Over time, appreciation for prints has grown significantly. We are now recognised as a part of Sotheby’s Global Fine Art division and it is not uncommon to see prints in Contemporary or Impressionist paintings’ sales. You will find print dealers at major art fairs such as Art Basel or a print specialist at an important gallery like David Zwirner. At the same time, the entire auction world has evolved, becoming a more moment-making part of the broader art community. Having prints accepted as valuable artworks within that sphere is both exciting and overdue.

Having prints accepted as valuable artworks within that sphere is both exciting and overdue.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, The Stoning of St Stephen, 1635, etching. Sold for GBP6,350 at Sotheby’s London, December 2025.

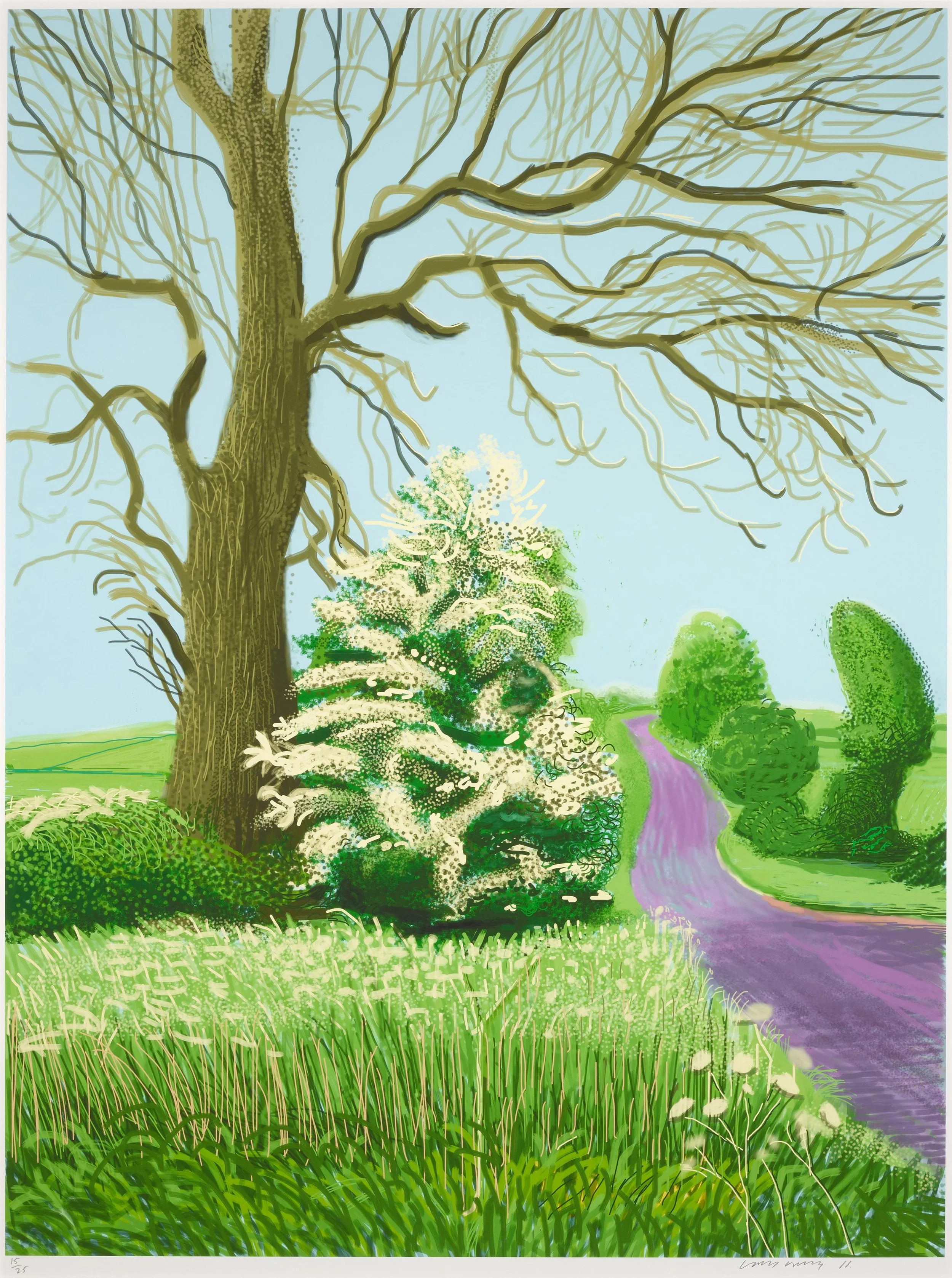

David Hockney, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty eleven) - 12 May, 2011, iPad drawing printed in colours. Sold for USD635,800 at Sotheby’s New York, November 2025.

What are your observations about shifts in the market across the categories of Old Master, Modern, and Contemporary prints?

There has been a notable shift in the art buying public’s interest away from the old and to all things new. One could spend under USD10,000 and acquire a remarkable etching by Rembrandt from the 17th century or over USD500,000 on a David Hockney print created 15 years ago on an iPad. The collector base for the former is fairly narrow, while the audience for the latter is quite broad. The focus has grown increasingly contemporary.

When I began my career, Sotheby’s had standalone departments for Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints. Now, we are one group, selling Old Masters solely in London and often finding it challenging to source important prints by Modern Masters such as Pablo Picasso or Edvard Munch. Today’s auction market is heavily dominated by pop art icons like Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein and living artists such as David Hockney or Ed Ruscha.

Exhibition display of Picasso prints. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

As a follow up to the previous question, what are the key factors driving these changes? To what degree, is it a response to supply of artworks in the secondary market?

Buying prints is a gateway to art collecting. There are more accessible prices for works by well-known artists. Our field attracts a young, successful crowd, excited to put their newly acquired wealth towards an appreciable signifier of what they have achieved. And frankly, most young collectors would prefer a large and colourful screenprint that anchors an entire wall over a small etching that one needs to examine closely to truly appreciate. Thus, as the greatest concentration of money has emerged from tech or new business innovations and those professions are dominated by people under 50, the average age of our buyer continues to go down.

Regarding availability, it is increasingly challenging to find older prints in good, saleable condition. The longer a print exists, in addition to the natural aging of paper, the more likely it was poorly cared for or framed with non-archival materials. As such, it has become somewhat unexpected to come across a work from the early 20th century or before that still maintains its intrinsic worth.

Buying prints is a gateway to art collecting. There are more accessible prices for works by well-known artists. Our field attracts a young, successful crowd, excited to put their newly acquired wealth towards an appreciable signifier of what they have achieved.

Sotheby’s Prints & Multiples recent performance statistics between 2021 and 2025.

How would you describe the interest for prints and its market activity in Asia or Southeast Asia?

Interest from this part of the world has virtually exploded in recent years and Sotheby’s is very eager to explore the activity we are seeing. In the past decade alone, the number of Asian bidders in Sotheby’s Prints & Multiples auctions has doubled; there has been a rise in the number of bidders overall and specifically younger ones. In 2025, the second highest concentration of these clients was from Singapore, behind Hong Kong, and ahead of Japan and China. The fact that the STPI is organising a print symposium and that Sotheby’s Singapore is holding an auction that includes prints on 25 January 2026 highlights the local interest in the medium and it will be thrilling to meet current and future print collectors.

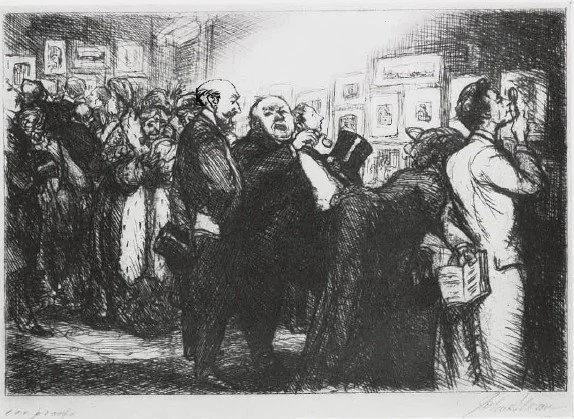

John Sloan, Connoisseurs of Prints, 1905, etching.

What is the approach at Sotheby’s when it comes to placing prints in auctions, as compared to private sale or having the works available online?

The auction versus private sale discussion is one we seem to have more and more often. It can be difficult to negotiate a deal for a work when the prices paid for other examples from the edition are easily accessible. Inevitably, the seller wants to achieve the highest historic price, and the buyer prefers to pay the lowest one. Therefore, we do tend to encourage clients to take advantage of the competitive landscape at auction. In a private sale scenario, a single buyer is approached with a set price and that number is very often negotiated downward. In an auction, bidders have to fight to be the successful purchaser, frequently paying more than they thought they would. On more than one occasion, we have had someone attempt to buy a work out of a sale, and when this does not come to fruition, they have had to then pursue it at auction, with their winning bid being considerably higher than their private offer.

That said, other issues are to be considered as well when deciding between an auction or private sale. Is the net price the seller has in mind in keeping with the specialist’s estimate, which is determined by the price history of the print, or is it much higher, requiring additional explanation to any prospective buyer? Timing is also a major factor: is there an auction on the schedule that is appropriate for the proposed material? Ultimately, we want to satisfy the consignor so we will proceed in the way they are the most comfortable.

Leslie and Johanna Garfield, photograph by Adam Reich.

Christopher Nevinson, The Blue Wave, 1917, lithograph in blue. Sold for USD17,800 at Sotheby’s New York, October 2023.

In 2023, you brought to auction prints from the Leslie & Johanna Garfield Collection. What did you learn from the experience of working on this sale?

It was an honour to be entrusted with presenting a portion of the Garfield Collection to the market. Leslie and Johanna developed many relationships over the years, with museums to which they donated, with dealers from whom they purchased. We wanted their collecting spirit to come through and to present the group of prints in a way that it did not seem like just another estate auction. It was extraordinary material; my personal favourites were the linocuts from the Grosvenor School and a rare Christopher Nevinson lithograph called The Blue Wave.

It seemed that everyone had a story about the Garfields’ print-buying adventures. Once on a trip to Cuba, Leslie decided to collect Cuban woodcuts, amassing hundreds, for which there is absolutely no resale market, simply because he was amazed by the beauty of the workmanship. Throughout the sales, in New York and in London, I discovered lesser-known artists and learned a lot about how much of one person’s work the market can absorb at one time. But most importantly, I was reminded of how passionate a true collector can be.

I discovered lesser-known artists and learned a lot about how much of one person’s work the market can absorb at one time. But most importantly, I was reminded of how passionate a true collector can be.

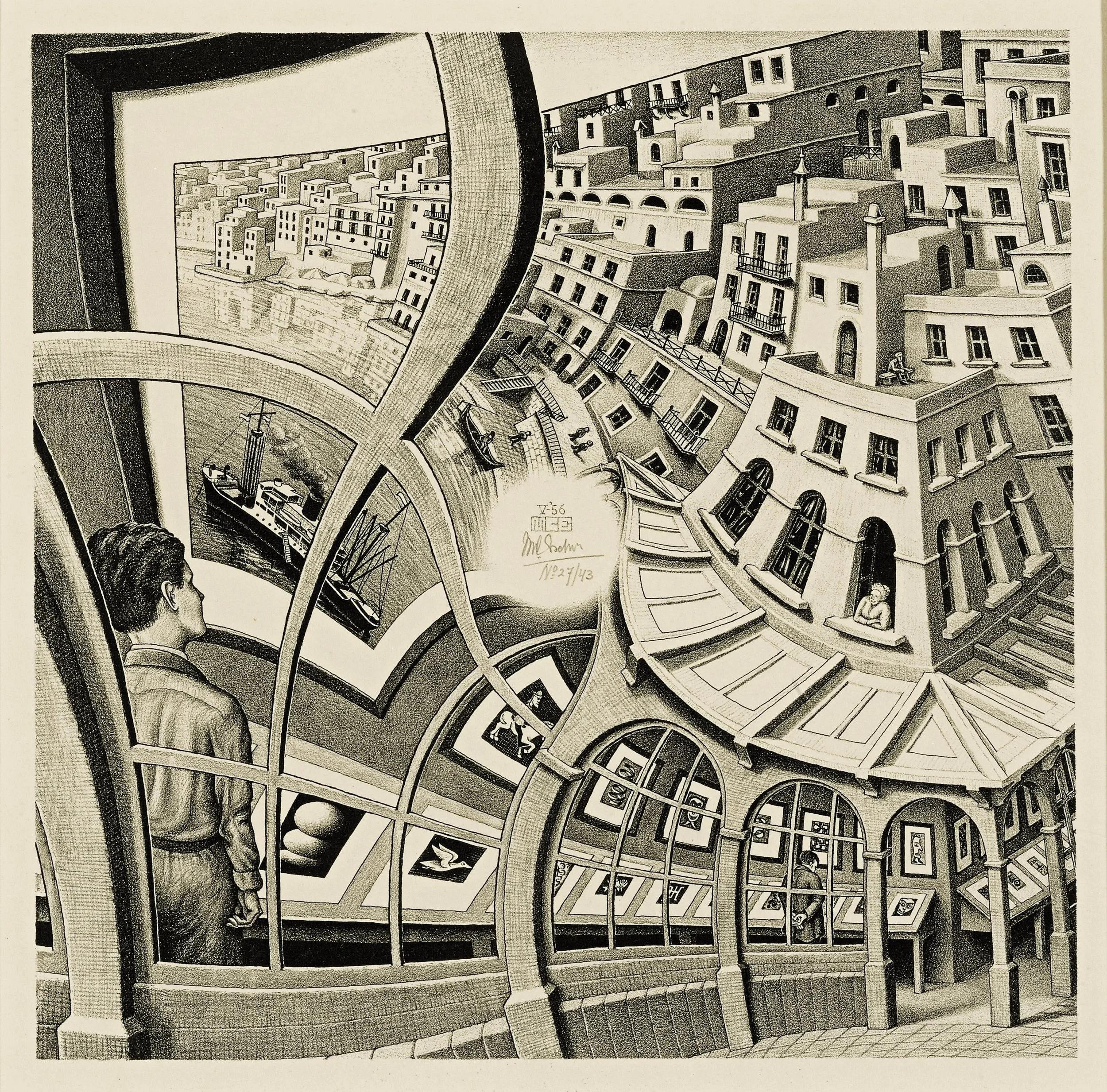

M.C. Escher, Print Gallery, 1956, lithograph. Sold for USD75,000 at Sotheby’s New York, April 2019.

In your opinion, do the qualities that make a compelling print change depending on the period the artwork was made? And if so, why?

I will never forget one of my first mentors saying that the art world has a “herd mentality”. 40 years ago, prints by Jasper Johns and French colour lithographs were incredibly popular. These days, the market for both is soft. For a very long time, no one thought twice about prints by M.C. Escher, yet now the prices realised for his work soar beyond pre-sale estimates. So, it is more that artists have their moments than a particular quality in a print that attracts attention. However, condition is incredibly important. Before purchasing a print, do get a full account of any imperfections, and whenever possible, examine the work first-hand.

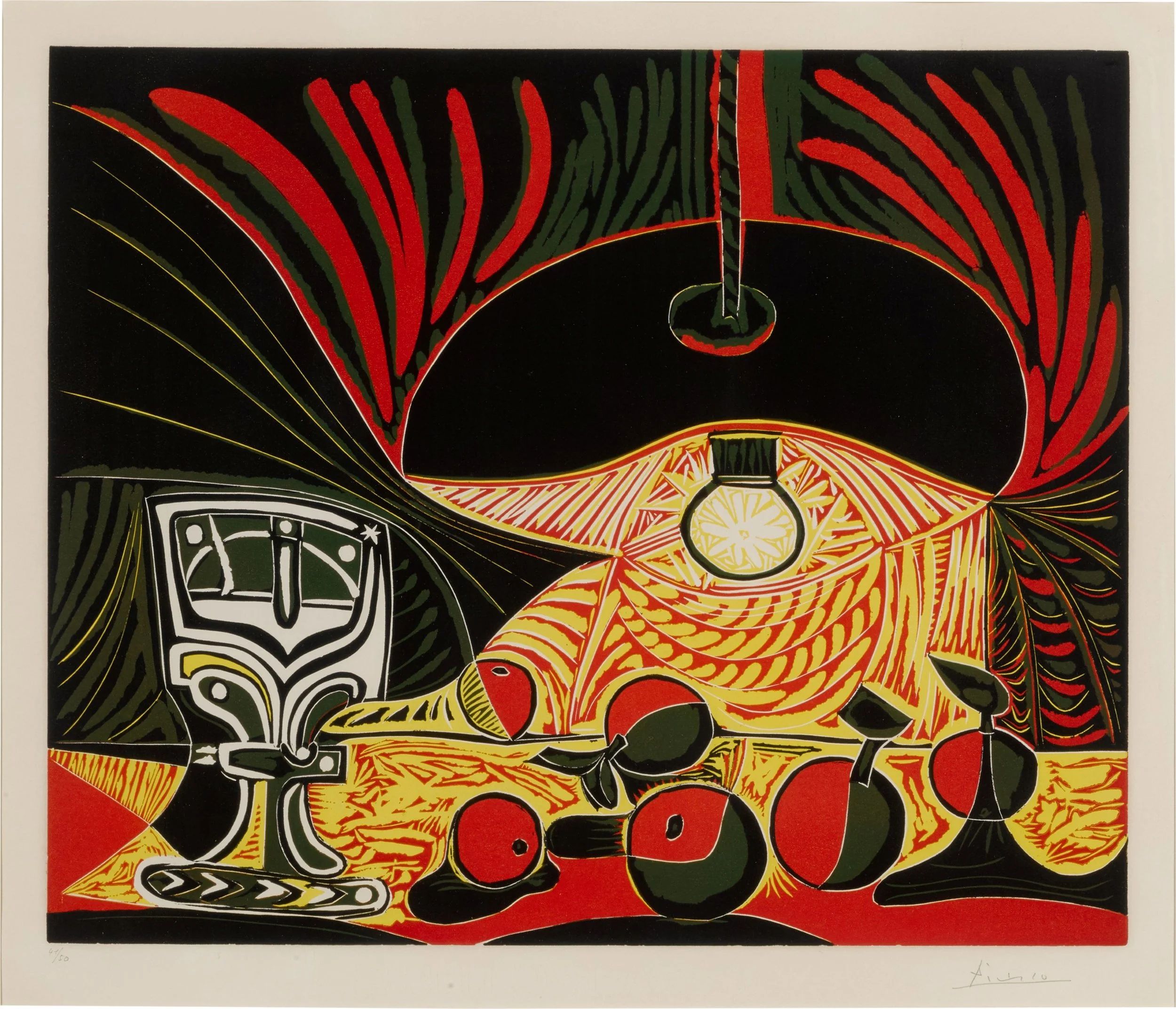

Pablo Picasso, Nature Morte Sous la Lampe, 1962, linoleum cut printed in colours. Sold for USD327,000 at Sotheby’s New York, October 2021.

What is one assumption/ misconception about collecting prints and multiples that you hope to address?

Prints are very misunderstood but the two things most common misconceptions are:

1. A low number in the edition or an artist’s proof impression is more valuable.

Every work in the edition was executed at the same time, from the same matrix, and they may not even be signed in the order they were printed. As such there can be no difference in price between 1/50 and 50/50.

2. A print is not an original.

Fine art prints are not copies or posters. Printmaking is an art medium just as painting or sculpture. Prints are original; they just are not unique. Many artists, for instance Pablo Picasso, were very devoted to printmaking. Not only was Picasso prolific but he used prints as a way of developing imagery that we later see in his paintings. Andy Warhol screenprints, famously, beginning with his Mao portfolio, very often preceded the paintings he made of the same subject.

What continues to excite you about the medium of print?

There is always something more to learn. Sometimes it is as simple as looking at the same work I have seen repeatedly but suddenly seeing it in a different way. Or a printer may teach me that a particular ink an artist used darkens as it ages, or discovering the best way to tell if a particular print is fake. I honestly do not think I will ever know everything and that is what keeps my job interesting.