One Year On: Support Measures for Artists

A Look in Singapore and Indonesia

Aspirations and Exasperations publicity graphic. Image courtesy of soft/WALL/studs.

Aspirations and Exasperations publicity graphic. Image courtesy of soft/WALL/studs.

Aspirations and Exasperations publicity graphic. Image courtesy of soft/WALL/studs.

When COVID-19 hit Southeast Asia early last year, government reactions varied from country to country. While some, such as Indonesia, lagged in response, others like Singapore were quick to cancel all public events and impose strict lockdowns in order to clamp down on the escalating situation. Artists within the vulnerable arts and culture sector that relies heavily on public events and tourism, immediately felt the whiplash from the extent of these measures. As such, governments introduced a slew of initiatives ranging from grants to government-funded exhibitions to sustain the sector as they prepare for the virus to become endemic.

Assuming that the number of COVID-19 cases is a reflection of government bandwidth, we explore two case studies, Singapore and Indonesia, as an exemplification of the range of government responses to COVID-19. Indonesia is currently one of the worst hit countries in Southeast Asia with ~4.1 million cases while Singapore’s cases stand at a total of ~68,000 as of September 2021.

Singapore

In April 2020, the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY) announced that it would invest SGD55 million through an Arts and Culture Resilience Package (ACRP). The MCCY further enhanced the package in March 2021 by SGD20 million, bringing the support for the sector to a total of SGD75 million. Some relief measures targeted at artists include:

The COVID-19 Recovery Grant where eligible individuals may receive a one-off payout of up to SGD500 if they experienced an income loss of at least 50% for at least one month during the peak of the pandemic;

The Self-Employed Person (SEP) Grant, which is a project-based support of up to SGD50,000 per project, aims at creating work opportunities and enhancing the skills of freelancers;

And the Organisational Transformation Grant (OTG) where the MCCY and the National Arts Council (NAC) would commission or work with suitable partners to co-create business transformation solutions to be piloted for the arts and culture sector.

Chok Si Xuan, neonate (6e656f6e617465), 2020, mixed media, found objects, silicone, electronics. Image courtesy of the artist.

For some fresh graduates entering the art industry, grant application was a challenge. Artist Chok Si Xuan says, “When I graduated from LASALLE College of the Arts in 2020, there was a lack of post-graduation opportunities as they were being cancelled due to the pandemic. Furthermore, because I had just graduated, I could not prove that I had a loss of 50% of my income, which made me ineligible for the COVID-19 Recovery Grant.”

Artist and filmmaker Tan Biyun was in a similar situation as Chok. Tan recounted in their interview for Aspirations and Exasperations, an ongoing interview project that began in 2021 to capture the mixed feelings of art workers in Singapore that is commissioned under Proposals for Novel Ways of Being, an initiative by National Gallery Singapore and Singapore Art Museum, that they had applied to the Self-Employed Person Income Relief Scheme (SIRS) three times but had been rejected.

They subsequently thought that the issue could have been due to one of the criteria that made them unable to apply for the scheme. Tan found that the criteria had been written in a way that may not have taken into consideration the art sector. For example, filing one’s taxes was a key criterion for SIRS. However, she raised that non-commercial artists may not have the ability to file for taxes.

Israfil Ridhwan and Into the Grass Fields (2021). Image courtesy of the artist.

To some art workers, the conditions of the grant was a barrier to entry. “I was keen to apply for the available grants but after reading through the details on the website, it felt quite cumbersome,” oil painter Israfil Ridhwan says. They explained that the grants could potentially be clawed back should the project fail to deliver the initial expectations laid out in the application. “The process does not account for or reflect the way art workers practise their art as it evolves in tandem with the project, making it challenging to fully pin down at the start of the application.”

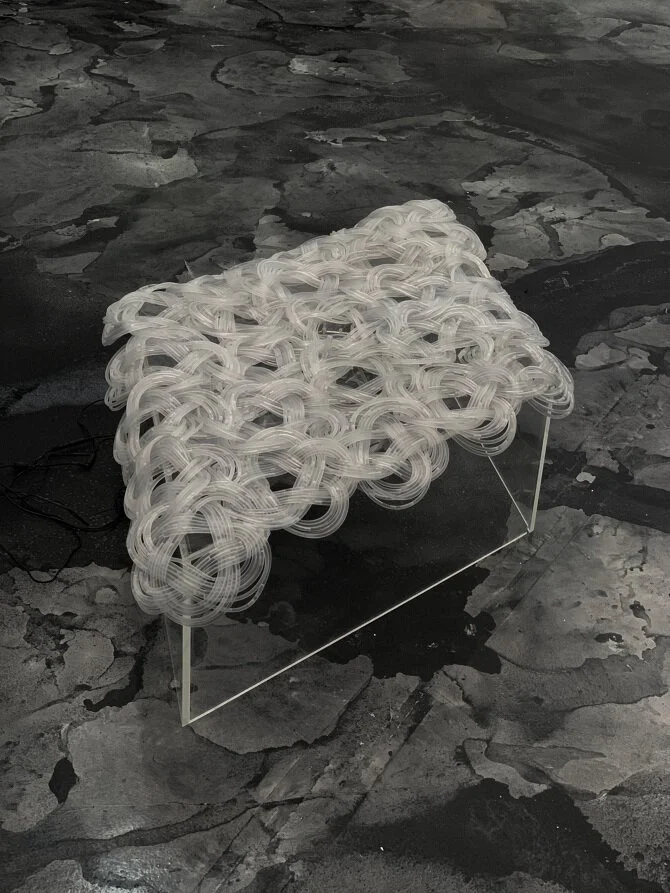

Chok Si Xuan, synapse, 2021, mixed media installation of woven tubing. Image courtesy of the artist.

Chok shared similar sentiments as Israfil. “Many grants are disbursed through organisations, which can influence the way creative projects manifest. As such, artists do not really get the chance to experiment freely,” Chok points out. However, the artists acknowledged that this was a means for the government to channel resources into specific areas, such as projects that focus on art and technology, an increasingly popular theme due to the pandemic.

A key point raised by Marcus Yee, an art worker who is also the editor of Aspirations and Exasperations, was that these challenges that artists face when applying for COVID-19 support measures have been prevalent even before the pandemic. Reflecting on their interview with artists during the project, “the challenges that art workers face are not exactly new. The pandemic simply exposed them, as evident from the survey that was published last year about artists being non-essential,” says Marcus. “Art making,” they add, “is still rarely seen as a form of labour in Singapore.”

That said, there are more opportunities for artists who dabble with technology as a medium and push the art sector to spotlight local artists. Moving forward, Marcus emphasises the need to have more conversations about fundamental issues regarding art workers, a point that Israfil also makes. They say, “While financial support has been generous, there is definitely still room for deeper understanding about the arts community and overall support for artists.”

Indonesia

South of Singapore, artists in Indonesia are facing their own unique set of challenges. According to UNESCO, the government reprogrammed the culture budget by reallocating approximately IDR132 billion (or approximately SGD12.4 million) to the Ministry of Education and Culture’s (Kemendikbud) Budget to support the COVID-19 National Budget. An additional package of IDR405 trillion (approx. SGD38 billion) was announced in March 2020 of which IDR150 trillion (approx. SGD14.1 billion) is channeled towards national economic resilience and recovery programs.

It was announced in November 2020 that artists may receive aid worth IDR1 million (approx. SGD94) through the Appresiasi Pelaku Budaya or Culture Artist Appreciation incentive, which would be distributed in two waves. However, a spokesperson for the programme has since come forward to apologise for the lag and inefficiency in the aid distribution. Incomplete data was also another obstacle faced during the distribution process.

The government had also permitted Individuals to tap on skills-upgrading programmes such as the pre-employment card programme to help facilitate workers to transit online at the start of the pandemic. In response to this aid, the Indonesian Arts Coalition (KSI) called on the government to better implement the card pre-employment programme for the art sector in order to help workers in the industry make ends meet.

Gudskul’s PPEs productions in Auditorium, 2020. Photo by Jin Panji. Image courtesy of Gudskul.

Artists on the ground share that in spite of the government’s targeted efforts, support has been more prevalent from the community and private sector. Gesyada Siregar, who is a curator, writer, artist and art organizer based in Jakarta and is currently the subject coordinator of Articulation & Curation at GUDSKUL: Contemporary Art Collective and Ecosystem Studies notes that in addition to government funding, GUDSKUL has turned to donations and international funding to sustain their activities during the height of the pandemic. “The situation,” Siregar says, “has pushed us to adapt and focus our activities on community driven initiatives. For example, we created PPEs for their local healthcare workers by using 3D printing technology. We also put together virtual exhibitions on our website.

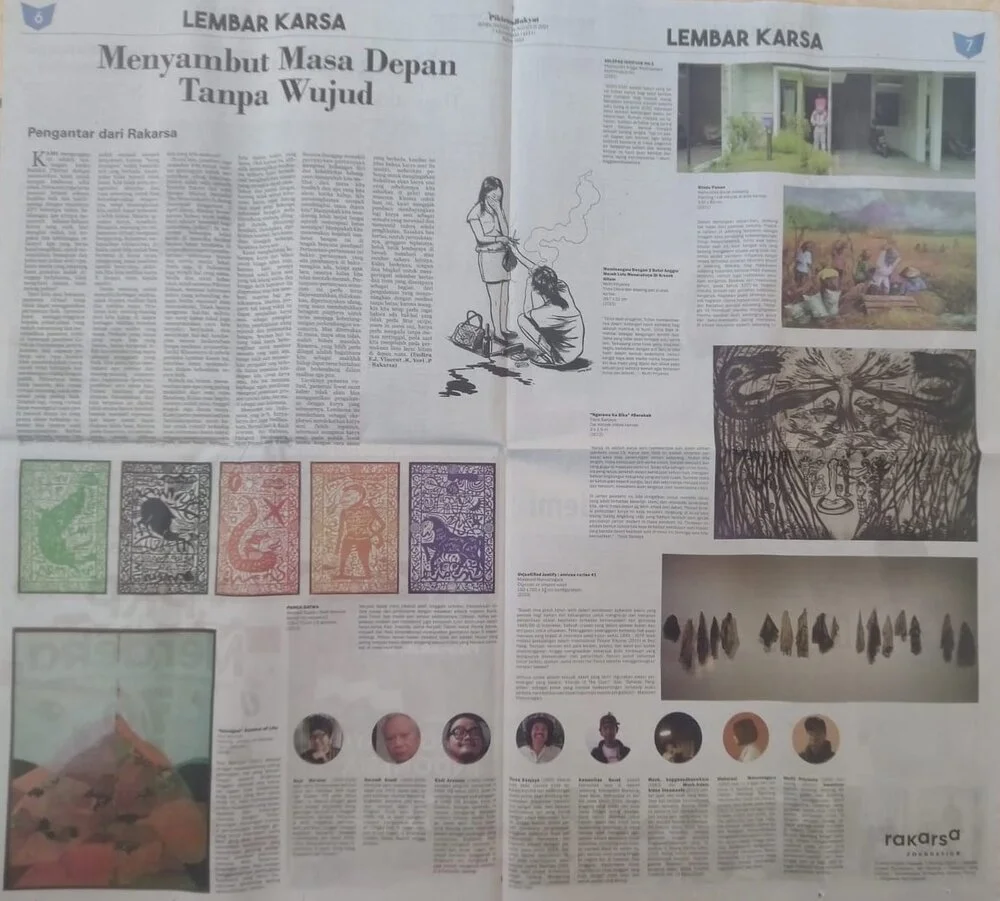

Newspaper exhibition project, titled Lembar Karsa initiated by Rakarsa Foundation Bandung. Image courtesy of Azizi Al Majid.

For Bandung-based visual artist, educator and curator Azizi Al Majid, art patronage mostly came from outside of Indonesia or through social media. “The lack of physical exhibitions had affected art sales so I turned to social media like Instagram to market my artworks and I managed to secure a number of sales in Taiwan,” Azizi explains. Their local arts community had also organised various initiatives for artists, for example, Rakarsa Foundation Bandung organised a newspaper exhibition, Lembar Karsa, to spotlight the local art community. One art collective in Azizi’s community had also put together a relief fund that was later used to set up a residency for newly graduated artists.

“It could be that the lack of faith in the previous government administration have ingrained the mentality that the art scene had to be self-reliant and community driven.”

When asked about where the communal spirit had stemmed from, Geysada opines, “it could be that the lack of faith in the previous government administration have ingrained the mentality that the art scene had to be self-reliant and community driven.”

According to artists based in Indonesia, many of the available government aid are targeted towards cultural workers, a broadly defined term that can refer to anyone involved in arts and culture. “If the (Indonesian) government wants to help artists, how can they identify them if they cannot define these terms?” Azizi questions.

With regard to the vague definition of cultural workers, Geysada says, “ I initially applied for the Culture Artist Appreciation incentive but a friend who works for the Indonesian administration shared with me that a broad range of cultural workers had applied, including those who had been more affected by the lack of live events such as traditional singers and live cafe singers. Since I have a stable income from my involvement with GUDSKUL, I decided not to accept the aid even though I was later informed that I qualified for it.”

Ultimately, the challenges faced by artists and art workers could indicate a larger issue at play that plagues the Indonesian administration. Azizi explains that the Ministry of Education and Culture employs a team of administrators who have experience in the arts field, and hence have a better understanding of ground sentiments. However, the government’s overall use of broad terms in its handling of the crisis has been less than helpful. That being said, the appointment of Hilmar Farid, a scholar, cultural activist and lecturer, as Director General of the Ministry of Education and Culture has been welcomed by those in the arts as a progressive move that could indicate better things to come for the community.

With translation from Bahasa Indonesia to English by Amirul Adli B Rosli.