Soundless Worlds: ‘Aesthetics of Silence’

Wei-Ling Gallery features Ivan Lam, Melati Suryadarmo, Arin Rungjang et al.

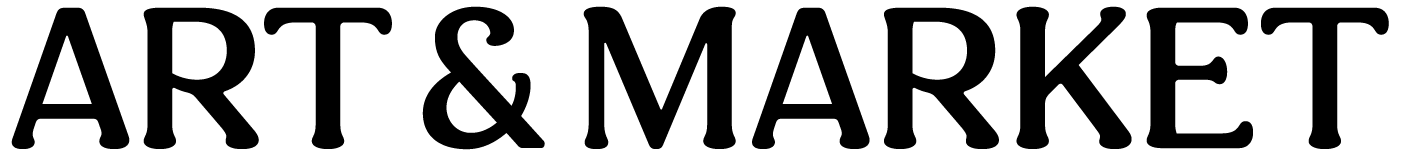

Arin Rungjang, Ravisara, 2019, commissioned by Toronto Biennial of Art with support from DAAD and co-presented with Harbourfront Centre, seven-channel video installation, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of Wei-Ling Contemporary.

Silence descends

on the city drone

thinks it a song

in need of punctuation,

gets drunk

in its hushed alleyways

drags and slips

on the elitist trappings

of the new museum

attracting

a new audience- Rajinder Singh, Trapping Silence, 2021

The first time silence engulfed Wei-Ling Gallery was in 2017, when Ivan Lam setup his first performance piece Curating Human Experiences 66:06:06. For a month, the artwork became the experience it created. Visitors would arrive, curiously but hesitantly joining the artist in his quest to reach a meditative state of silence. Some would sit and leave abruptly, while others lingered. In this small circle, and between interactions and distractions, a dialogue was taking place, even though it was non-verbal. Much like Marina Abramovic´s performance piece The Artist is Present, silent encounters possessed as much a transformative force as sounding encounters that echo long after their ending. If silence was an on-going act in Ivan´s installation, then sound was an accidental interruption. Within the small universe created by the performance piece, silence and sound necessitated each other´s existence. Each force interrupted the other, fading in and out of view. Yet, both forces were rooted in the need to be witnessed. In a way, at the heart of their necessary contradiction, sound and silence are deeply and intimately interdependent.

Ivan Lam, Curating Human Experiences 66:06:06, 2018, installation and performance, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of Wei-Ling Contemporary.

Now in 2021, Ivan´s performance piece bears an uncanny resemblance to our daily life. Since the beginning of the pandemic, isolation has forced us into a new experiential reality, where non-action, silence, stillness, and absence have become primary forces in our daily lives. Those forces restructured our routines, as well as our vocabularies. Most importantly, they blended the boundaries between our physical and virtual identities. At once, we were witnessing the birth of a hybrid reality, while being deeply rooted in the physical pain of a world where even touch and closeness became threatening weapons to our survival. If our lives were an on-going sound, the pandemic came as an interruption — an absolute silence. Together, yet apart, we wondered what it meant to interrupt, to veil, to hide, and to silence. As lockdown locked us in place, it pushed us to generate new spaces of communion and new modes of interaction. In the midst of this new, overtly still reality, our desire oscillated between the need to be seen and the need to subvert and retreat to the theatrical world of the imagination and make-believe. In the exhibition ‘Aesthetics of Silence’, these sentiments are explored through the works of eight international artists that use a variety of different artistic languages and practices to highlight the power of the soundless world.

“As lockdown locked us in place, it pushed us to generate new spaces of communion and new modes of interaction. In the midst of this new, overtly still reality, our desire oscillated between the need to be seen and the need to subvert and retreat to the theatrical world of the imagination and make-believe.”

These sentiments are first echoed in the theatrical works of Roger Ballen, specifically his exhibited series Roger the Rat, where the artist uses a part-human, part-rat creature to invite us into a playful and theatrical depiction of what it means to live an isolated life outside of society. Roger the Rat works with the idea of a muted body that inhabits a soundless world. This means to be heard, the body needs to be seen, to be looked at, and to be followed. Such a body treats movement and action as a form of elaborate speech. Following this line of thought, Roger’s soundless narrative unfolds through a series of awkward and sublime movements and actions that mirror the absurd and fantastical world of the human psyche.

Within this world, comedy and playfulness are used as forces to dispel anxieties rooted at the heart of the subject. Lauren Berlant writes that what we find “comedic is sensitive to changing contexts” (2017). Indeed, in another year, the story of ‘Roger the Rat’ might have been viewed as an amusing adventure. This year, however, it is a disturbing narrative that trips over the borders of the not funny. For we, as viewers, live a life that is not much different in rhythm than that of ‘Roger the Rat’. It is precisely in his soundless narrative that uses humor, comedy, clumsiness and awkwardness that Roger helps us to test and figure out the new rhythm of our distorted realities within the vulnerable and protected space of the imagination.

Soundless narratives are ever present in this exhibition. Rajinder Singh channeled the introspective time during lockdown into a poetry book titled Trapping Silence (2021), which explores his fraught relationship to isolation, the past, and the silence that has descended and swept us unknowingly. Throughout the book and especially in his poem that bears the same title, Trapping Silence, Rajinder portrays silence as an entity — a sort of invisible body that changes the fabric of the city. It lurks in space, adding weight, slipping in and out of conversations. But here, silence is depicted as an antithesis to life — a kind of trap that keeps you in place, restrained and unable to participate. Singh wrestles with the notion of silence as a sanctuary or silence as a trap throughout his introspective writing. Sometimes he embraces the spiritual and emotional qualities it offers, while other times he sees himself disappearing from “life into silence”, as if hopelessly withdrawing himself from view. This tension comes and goes in waves, each time sweeping with it new audiences and releasing others back on shore. Perhaps, silence is a temporary and transformative journey that each one of us takes to understand the complexities of our place in this world.

Melati Surydarmo, The Dusk, 2010, installation view. Image courtesy of Wei-Ling Contemporary.

Soundless narratives, however, are not only reserved to the realm of the imagination. In Melati Suryodarmo’s work The Dusk, we witness bodies in a suspended state of being, attempting to escape an impossible state of silence, yet failing to exit it. What Suryodarmo is reflecting upon is the effects of growing up in a culture of silence. If Joan Didion was right in her saying “we tell ourselves stories in order to live,” then silencing our narratives, whether personal or cultural, immobilizes our life force (Didion 2006). Suryodarmo’s practice is conceived of as a series of poetical actions, which combine a sequence of words and movements to create a layered and embodied narrative. A few minutes into Suryodarmo´s film, we witness several women in a state of suspension. Waiting, looking out, gazing in, and pacing around an empty house they are unable to exit:

Tired bodies

Disconnected bodies

Betrayed bodies

Bodies in waiting

Bodies left motionless

Bodies rigid and stiff

Bodies disconnecting

The women in Suryodarmo’s film are locked in place. Even in their potential, they are immobile. It is as if they are in a state of waithood, awaiting their own bodies to arrive. Towards the end of the film, a soft voice shatters the silence, spelling out a song that mobilizes the women. As the final scenes suggest, sound forces the body into movement away from the empty estate, both physically and mentally. Perhaps, the remedy to generational trauma, afterall, begins in the act of storytelling.

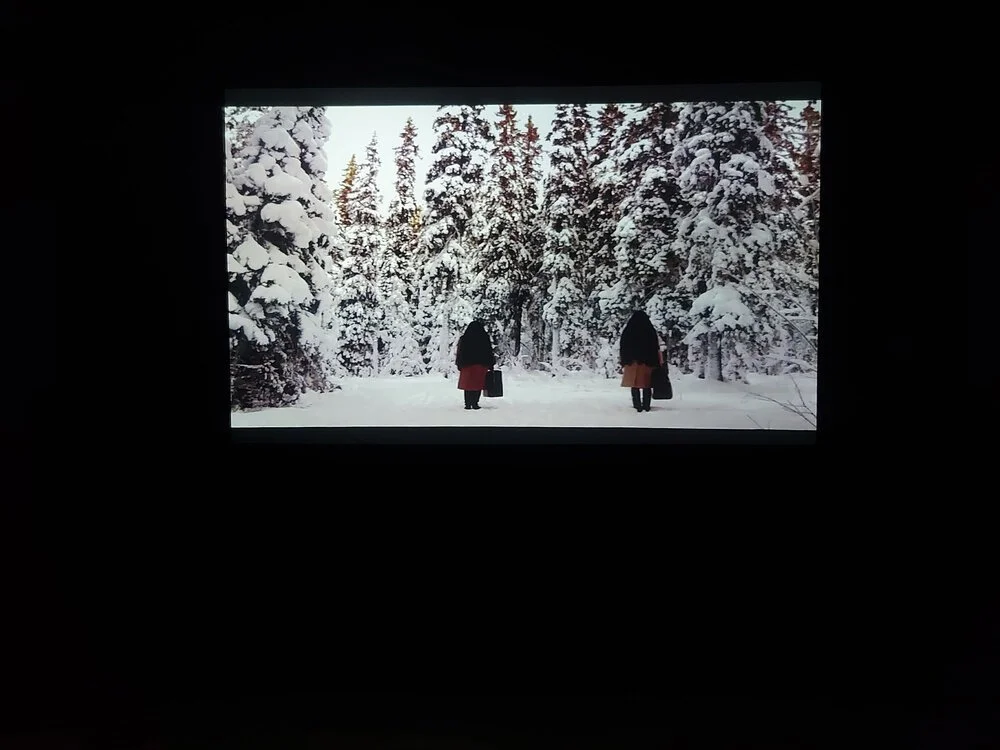

H.H.Lim, I miss you, 2020, single-channel video, 2:01 minutes. Image courtesy of Wei-Ling Contemporary.

The song that erupted was not necessarily redemptive, yet it was not an erasure either. What the song represented is the unlocking of narratives, the end to silence and a beginning to sound, and therefore a reclamation of agency. Another artist in the exhibition, H.H Lim, looks at the practice of active remembering through performative storytelling. In Home Song, we witness again what it means to hold one’s history in one’s body — to be marked by narrative at the cellular level. In the performance piece, Lim breaks out into a rhythmic song that expresses his longing for his homeland Malaysia as he sings it from Italy. Lim lightly uses a stick to tap on his body while singing, as if to jolt his body into a state of active remembering. Through this short performance, Lim holds his narrative, his history, and his homeland at the core of his body. It is only through the body that he can remember and express his longing across distance. While Home Song is filled with sound, his other work I Miss You is laden with silence. Using Chinese ink and a calligraphy brush, Lim delicately writes I Miss You, and awaits as it slowly fades. The two performative works appear to be in a dialogue with one another, showcasing how memory persists through sound and repetition, and dies in silence and forgetfulness. Meditating these two works is somanywonderfulsecrets, a neon sign that is initially difficult to decode as the words are pressed into each other. This sign enters into a sentimental dialogue with Lim´s other exhibited works, except here it does not evoke a story, instead it holds together the feeling of mystery and oscillates between the desire to reveal and conceal secrets.

Further interrogating the phenomena of cultural silence is Arin Rungjang, who exhibits a 7-channel video work titled Ravisara (2019). Through these video works, Rungjang presents an intimate portrait of six women who have emigrated to Germany from different parts of Thailand. During his stay in Berlin in 2018, the artist devoted himself to the Thai community, collecting stories of migration, violence, discrimination, loss, and abuse of power. In his video installation, those stories are unraveled, as the women appear on their own, sometimes with others in close-ups, and other times as a group of six, with limbs draped over each other's shoulders. In each configuration, the women utilise their bodies as a form of speech. The intimate atmosphere generated by their bodily presence presents a stark contrast to the harsh, systematic, and policy-oriented language used to describe migration. Here, performative gestures become a language that reflects the intense and physiological memory of migration. Through movement, Thai immigrant women rely on body memory to recall stories that reflect the arduous journey of finding a new, personal identity in new conditions that are influenced by postcolonial power structures and prescribed gender roles. This practice of active remembering through embodied memory functions as a tool to reconnect with the most intimate and visceral experiences of the self. In emphasising the role of body and gesture in storytelling, Rungjang reinvents documentary modes of representation by creating a silent space to position the personal and the embodied memory within the global discourse on migration.

And while every act of silence possesses a political dimension, Heather Dewey-Hagborg zooms in on the analytical silence of surveillance systems in her installation How Do You See Me? She interrogates the following question; how do machines see us? How does the silent gaze of surveillance systems record us, analyze us, and give virtual shape and form to our abstract data? In a world where we are constantly looked at, studied, and analysed by cameras and algorithms, silence around and through these mechanical eyes is used as a tool to maintain power structures between governments and citizens. In the installation, Dewey-Hagborg utilised adversarial processes and algorithms designed to deceive machine learning systems into generating portraits that resemble the artist´s face, although in reality that bear no resemblance to it or to any human face. Through this subversive and generative experiment, the artist highlights the silent discourse around security and the danger in handing control over to intelligence and automated systems that can easily distort and replicate our identities.

As Aesthetics of Silence demonstrates, perhaps the appeal of the non-verbal in art reflects our desire to reconnect with the pre-cultural parts of ourselves. Such are the atmospheric and meditative works of Robert Schaberl. His circular surfaces showcase a slow transition of colours through different angles, not necessarily reflecting a meaning, but inviting the viewer for a silent communion. Schaberl uses the universal symbol of the circle to signify the natural cycle of life that oscillates between beginnings and endings. Although often, these seemingly opposite cycles are one and the same depending on one's perception. Schaberl´s composition reflects this interplay as they shift in movement and intensity according to the position of the viewer in relation to the work. Light and movement play a primary role in these compositions, for only a person in motion can fully experience the meditative effect of his works. The intensity and movement of light continues to change the work, heightening the visual experience and unraveling new ways of seeing the work, while bringing into climax a solid state of tranquility.

Ivan Lam, Breathe, 2020, installation view. Image courtesy of Wei-Ling Contemporary.

Much like its beginnings, what concludes the exhibition is Ivan Lam´s performance piece Breathe (2021), a series of video works made on TikTok depicting the artist breathing in and out. There is a comical aspect to Ivan’s use of TikTok as a medium for artistic practice. If there is a window we collectively looked through during the past two years, it would be the windows of our phones. Simultaneously, the same device and apps that disconnected us from real life became the only tools to connect us once again. Perhaps, there is something in that contradiction that we should ponder as we breathe in and out with the artist.

References:

Joan Didion, We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live (New York City: Knopf, 2006).

Lauren Berlant and Sianne Ngai, “Comedy has Issues”, Critical Inquiry 43 (1), 233-249.