Midpoint: Erika Tan

A position outside disciplinary, national, and cultural boundaries

Midpoint is a monthly series that invites established Southeast Asian contemporary artists to take stock of their career thus far, reflect upon generational shifts and consider the advantages and challenges of working in the present day. It is part of A&M Interviews and builds upon the popular Fresh Face series.

Erika Tan with her collaborative work A Legacy for a Future Unknown (2021-22). Image courtesy of Jo Underhill.

Erika Tan is a London-based Singaporean artist. Her research-led practice focuses on the transnational movement of ideas, people, and objects. Erika is also a Reader in Contemporary Art Practice and the Course Leader of MA Fine Art in Central Saint Martins, London. In this conversation, I invite Erika to share her formative experiences, connections with Southeast Asia, as well as recent projects which involve reviewing museum collections and objects.

Erika Tan, Barang-Barang, 2021, installation view at Taipei Fine Art Museum. Presented as part of the group exhibition Art Histories of a Forever War: Modernism between Space and Home (2021-2022). Image courtesy of the artist.

Looking back, could you share a decision or event that marked a significant turn/moment in your path as an artist?

I think of my formative years of playing in the sand on the Malaysian coast, making mud pies in the back yard, messing around with candle wax at parties to form shapes or casts of my fingers and getting extremely engrossed in paper-cutting every time I was sent to my room for bad behaviour… These experiences led to this point today! But if I were to point to something more cognitive, then I would say it was the moment I realised that the gallery was the only location that might be able to support the work I had made. I studied anthropology in university and took a module on ethnographic film there.

When I left university, I took up evening classes in filmmaking. I had applied for two Masters courses, one in documentary film and another in moving image within an art school. I was not sure which one to accept. It was only after I received a grant to make a video work and found myself making a multichannel work that I was forced to realise that the documentary format usually ended up as single screen broadcast, or cinematic release. If I were going to continue to make multichannel non-linear work, which is what I found myself repeatedly drawn to, I would need to locate the work in the gallery. I chose to go down the art school route and that is my “story” of becoming an artist – a kind of failure of becoming a documentary film maker!

Another key moment was when I realised that being an artist was quite a risky business, a kind of unintentional gambling with one’s life in terms of time and financial stability. Initially, that was fine as long as I could support myself and become involved in making things I wanted to. But economically, it was extremely precarious and often exhausting. As an artist, one is usually working outside of any institutional frameworks of support. I found myself saying “yes” to everything and then managing the troughs and peaks of the freelance gig economy. In the early days of my practice, I also curated projects. With the curatorial roles, even though I was independent, the remuneration was more considerate and tied more to the amount of work I did. As an artist, so much labour is often unseen, and artist fees hardly ever anticipate or acknowledge the extreme self-exploitation we as artists do to ourselves! Anyway, as a curator of a large urban art space development, I suddenly became ill with appendicitis three weeks before the installation of the show. There were various complications, and I ended up coming out of hospital just in time to go into the exhibition set-up. There was no time to be ill and there was no additional money to bring in someone else to replace me, so that was me back up the ladder. I realised then how vulnerable I was to unexpected problems. Whilst it took me several more years to do anything further about this, it was a wake-up call and led me eventually to take up teaching roles for more financial stability.

Erika Tan, The 'Forgotten' Weaver, 2017, close up shot of the fragmented screen with Singaporean dancer Som Said performing in The National Gallery Singapore. Exhibited at the Diaspora Pavilion, Venice Biennale in 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

What has been a milestone achievement for you, and why has it been particularly memorable?

Possibly the most significant moment was when I received the first invitation to show my work in Singapore in 2003. I had left Singapore before my studies in the United Kingdom and did not have any connections to the art community. On a visit home, I went round various art spaces and met Binghui Huangfu and Philip Francis, then curators in Earl Lu Gallery at LASALLE College of the Arts in Singapore. They were putting the exhibition Science Fictions (2003) together and through a casual conversation I mentioned some of the work I was developing that incorporated ideas of anthropometry and questions around disciplinary problems with anthropology. It was a lucky co-incidence that the work had some resonance with their curatorial project and I came back the next year to install the work Floor Games & Rubix Cubes (Sites Of Construction Series) (2003). What felt significant to me was that despite being made outside of the Singapore context, and being quite niche, my work might still be perceived as having some value or relevance in Singapore. The show also included artists such as Zabok Ben-David, Emily Chua, Susan Hiller, Feng Mengbo, Lisa Reihana, Shen Shaomin, Vivan Sundaram, Chris Welsby. The catalogue was written by Chua Beng Huat, Binghui Huangfu and Ray Langenback, with a text by Marian Pastor Roces. It was a great introduction to working in Singapore and in the region.

This first invitation led to other opportunities and a sense that it might be possible to develop a transnational practice, connecting Singapore and the UK. Exhibitions that followed included the first Singapore Biennale Believe (2006) curated by Fumio Nanjo, Roger McDonald, Sharmini Pereira and Eugene Tan; the launch of Gillman Barracks with Encounter, Experience and Environment (2012) curated by Eugene Tan; a National Arts Council Singapore funded solo project with NUS Gallery called Come Cannibalise Us Why Don’t You (2013) at the invitation of Ahmad Mashadi and curator Shabbir Hussain Mustafa; an inaugural commission with National Gallery Singapore for their launch in 2015 and at the invitation of curator Mustafa titled Apa-Jika, The Mis-Placed Comma; and more recently a collaborative project with Adele Tan called Slideshow Party – a Feminist sharing of art and other provocations (2022-23), held at Singapore Art Museum on the occasion of the 7th Singapore Biennale Natasha. These have been important moments, not just to share work and “come back home”, but to also engage with and maintain dialogue with artists and curators working in and from Singapore.

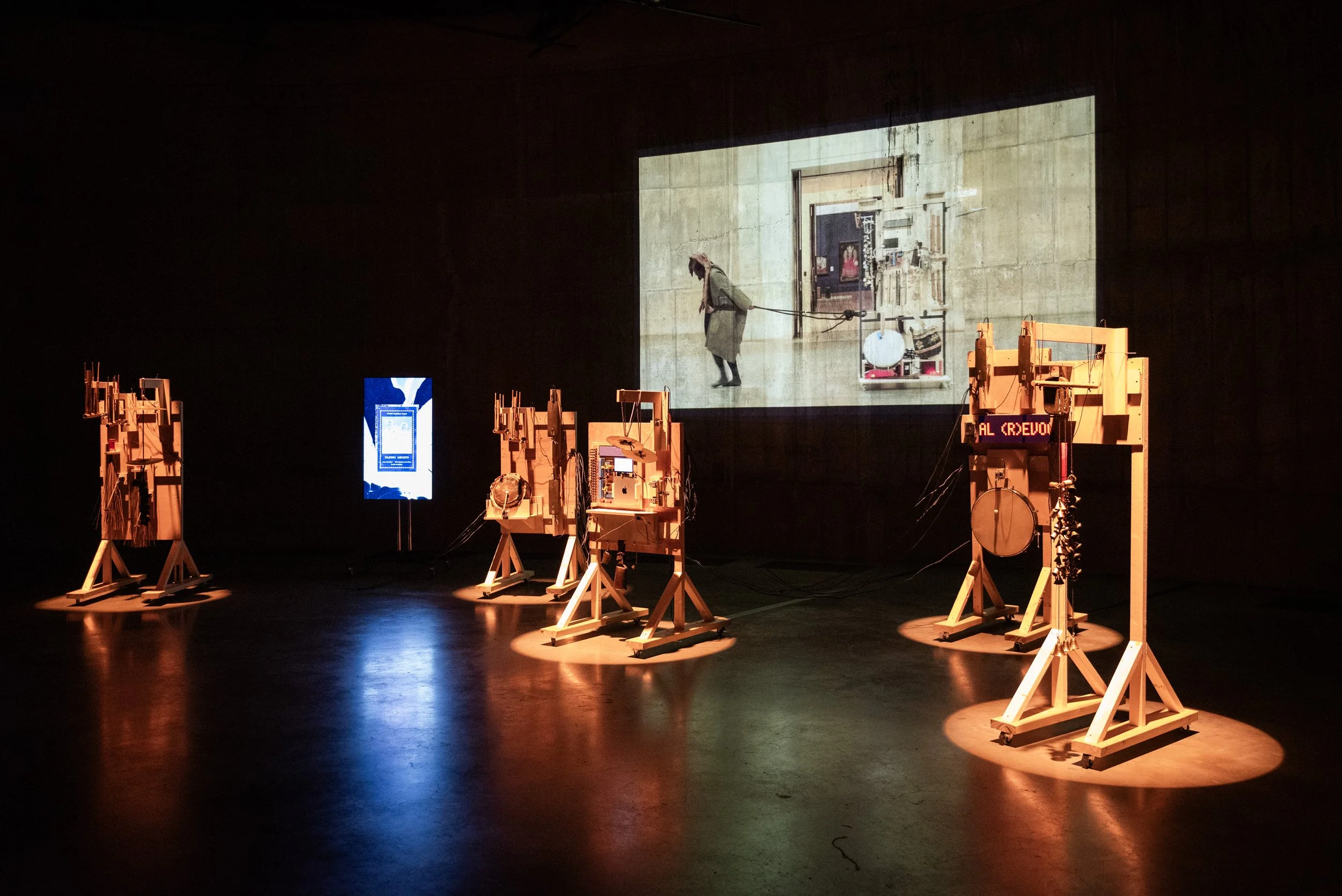

Erika Tan, Ancestral (r)Evocations, 2024, installation view in South Tank, Tate Modern. Presented as part of Museum x Machine x Me: Artists Display, 2 to 6 October 2024, Tate Modern. Photography by Ariel Haviland. Image courtesy of UAL and Tate.

And there are also more recent achievements that hold special significance.

The other two milestones that come to mind are connected to each other. When I realised that I might need to be more intentional with the decisions I was making in being an artist, I scribbled down a couple of things I might want to “achieve” as an artist. One of the ideas was exhibiting in the Venice Biennale and the other, a major venue in London such as Tate. I do not believe in the idea of “manifesting” one’s desires, but having identified something ambitious, I had in some ways set myself a challenge. If not actually reaching these “goals”, then at least being less complacent with the value of my time, and maybe engaging with the need for more of a strategic approach in my life. It is not only about the making of the work, but also everything else that surrounds it.

Since then, I have shown work in Venice, not in the Singapore Pavilion as I had imagined or hoped, but instead as part of the first Diaspora Pavilion in 2017 curated by David A. Bailey and Jessica Taylor from International Curators Forum (IFC). Despite four or five attempts at proposing work for the Singapore Pavilion in Venice, and getting to the interview stage, this just has not happened.

During the same year that I was showing in the Diaspora Pavilion in Venice, Zai Kuning showed Dapunta Hyang: Transmission of Knowledge (2017) in the Singapore Pavilion. The centrepiece was rattan woven into a boat-like form, a spectral reference to the lesser-known narratives of the orang laut (sea people) who are central to, but often marginalised in the received narratives of Singapore statehood. I showed The ‘Forgotten’ Weaver (2017) as part of the Diaspora Pavilion. It is a weaving together of transportation strapping into a large “expanded” loom with video references to the little-known account of Halimah Binti Abdullah, a master weaver from Malaya who died in the UK while demonstrating her craft in the Malayan Pavilion that was on display in the 1924 Empire Exhibition in London.

As for the other moment, this was last year when I exhibited in the Tate Tanks, London. I remember going to an event at Tate where we were taken down in hard hats to the basement of what used to be the oil storage tanks for the power station. The architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron was transforming these oil tanks into spaces for live art, performance and installation. A few years later, at the Expanded Cinema Conference (2012) held at Tate, I saw the work of Liz Rhodes there and imagined how incredible it would be to work in such charged spaces. Last year this became a possibility, and I showed Ancestral (r)Evocations (2024) as part of Museum x Machine x Me. It is an installation that filled the space with sounds triggered by the Tate’s collection data and played on diagnostic instruments made from fragments of Southeast Asian instruments. If there is the concept of a bucket list for artists, this was one of mine ticked off!

I do not believe in the idea of “manifesting” one’s desires, but having identified something ambitious I had in some ways set myself a challenge.

Erika Tan, A Legacy for a Future Unknown, 2022, installation view at Newnham College Cambridge. Image courtesy of Jo Underhill.

Erika Tan, in collaboration with Dansity, AMOK:KOMA (video still), 2021, presented at Jakarta Biennale 2021, The National Awakening Museum. Image courtesy of the artist.

Could you walk us through a typical work day, or a typical week? Are there routine(s) you follow to nourish yourself/your artistic practice?

There is no typical day. My practice has often taken shape in response to the conditions, possibilities, and limits associated with specific projects or commissions. Sometimes the work is supported by residencies, fellowships, or research periods, each coming with their own parameters and timeframes. As the work often arises out of a period of research which helps determine the method or approach and mediums employed, I often find myself in positions of unknowing. For me, this is crucial, but not always easy to hold onto especially when curators and commissioners want to feel secure in their decisions to work with you!

In terms of recent projects, a 150th anniversary commission with Newnham College Cambridge titled A Legacy for a Future Unknown (2021-22) resulted in a series of 60 banners, commemorative plates and a video work. The process was collective in terms of working with Newnham college residents to collect texts for the banners, then running workshops on gathering and pressing plants from their gardens to make cyanotype prints that would later be used in the work. I also collaborated with students to make the sound for the video work, and all of this meant going back and forth between Cambridge and London, moving between different processes and mediums.

With Ancestral (r)Evocations (2024), I found myself needing to reach out to people with coding skills and machine learning and data experience. A lot of time was spent online trying out various AI apps and looking through museum data files. I started with making a prototype diagnostic instrument, and this meant working in a woodwork shop putting elements of Southeast Asian instruments together. We then used the prototype to film inside the Tate, among works with references to Southeast Asia by Kim Lim, David Madella, and Vong Phaophanit. So the range of activities to get this project off the ground was diverse and they were done while juggling teaching and being a mum to a teenager! I have to say, sometimes making work is truly a family affair. I could not have made this work without the additional input, physical labour, and patience of both my partner and my child.

Another example is AMOK:KOMA (2021) which was made during the COVID-19 period. It was an installation at the National Awakening Museum for the 2021 Jakarta Biennale. The rehearsals were carried out remotely, where each participating dancer Zoom-ed in from home. On the day of the final shoot, Jakarta had opened up, but in the UK, we were still house bound. I found myself watching from a distance and trying to direct the cast and crew throughout the night using bits of English, Bahasa Indonesia, and various hand gestures. It was extremely chaotic, but also fun and required a lot of trust and flexibility!

Each project comes with its own learning curve, sense of pace, duration, and parameters. I would like to share a final example, Sour Kanna (2023) which was commissioned by curator Caroline Ha Thuc as part of an ongoing project she curates from Hong Kong called The Asian Cocoa Project. The exhibition titled In Stranger Lands (2023) which focused on Asian chocolate and had plans to be shown in Vietnam, Hong Kong, Yogyakarta, and Manilla led to me making Sour Kana while traveling in Thailand as part of a research project called Circumambulating Objects: On Paradigms of Restitution of Southeast Asian Art (CO-OP). Before going to Thailand, I had been thinking about the material conditions of chocolate, specifically in relation to the gap between cocoa growers and chocolate consumers. Whilst international cocoa or chocolate trade is supported by refrigerated shipping, when I was a child in Singapore, the only chocolate we had access to was the kind that either had a wax covering to keep it in shape or additional elements added to it so that the chocolate would not melt. I found myself learning how to make chocolate on my kitchen table and casting it into the shape of sour kanas, the salty prunes of my childhood. These were then taken to Thailand and filmed in various locations in the heat of the midday sun.

Filming Apa Jika, The Mis-Placed Comma, at National Gallery Singapore, 2015.

Collection of Fay Tan art works and ephemera. Research process for Barang-Barang on display for Open Studios Stanley Picker Fine Art Fellow, Stanley Picker Gallery, 2020.

Could you describe your studio/ workspace? How has it evolved over the years? What do you enjoy about it, and what do you wish to improve/change?

Well, I think I have had my fair share of terrible studios! My first studio was part of a studio award in Central London. I was grateful for this opportunity, even though the space backed onto an alley way which was used as the local toilet and a place to shoot up. Although I could not see what was happening there, as the windows were very small and high up, I could hear everything! I also went through a period of living and working in an old industrial building. Due to the high studio and housing costs in London, I found myself doing what many artists at the time were also doing, which was to live and work in their studio spaces. Often under-developed, these spaces were cold and damp. I used to sit at a desk with a duvet on, the heater placed under the table and a hot water bottle strapped to my body!

Then, I received an ACME studio award which was an amazing opportunity to legitimately live in an old fire station with subsidised rent, inclusive electricity, a communal washing machine and some brilliant artists as neighbours! This support helped me focus primarily on making work. However, I became used to the live-work set up and have found it difficult to progress to a separation of personal life and studio work. I currently have a studio space in a large complex of studios about 20 minutes away. But I am still developing most of my work, ideas, and research from home or at a particular site, and only going to the studio when I need more space to get things made. Many of my moving image works have also been shot on site, from historic houses such as Saltram House in Plymouth where director Ang Lee shot Sense and Sensibility, to City Hall in Singapore before the launch of the National Gallery, and most recently The Wellcome Collection and Tate Britain.

What has become easier or more difficult to do as time has gone by?

It takes time to make work. This is especially the case if one has a research-based practice that seeks to also hold indeterminacy as part of its methodology. As life has become busier it becomes more difficult to hold onto various threads and strands of thought, detail, research in and between the various other things. Work and life events compete for time. Keeping up with friends, family, social networks and art events, or technological developments and new opportunities is becoming increasingly complex. I still hold out for the idea of a long, collaborative open-ended way of working, where the people I enjoy working with might become a continuum in the process. I am not sure what kind of a world this could exist in, but currently it is not my world! But this is something to work towards all the same and I have a ready list of people who I would love to work with again. I also have a list of people who I would avoid at all costs. So perhaps another answer to this question might be that it has become easier to say no to projects, and knowing where my limits lie.

I still hold out for the idea of a long, collaborative, open-ended way of working, where the people I enjoy working with might become a continuum in the process.

Filming of Vong Phaophanit’s Neon Rice Field (1993), with his daughter and cinematographer Chanthila Phaophanit, at Tate Britain. As part of Erika Tan’s Ancestral (r)Evocations (2024). Image courtesy of the artist.

Two recent projects you are involved in deal with collections, provenance, and art histories: Transforming Collections Artist Research Residency with Tate Modern; and Circumambulating Objects: On Paradigms of Restitution of Southeast Asian Art (CO-OP). What sustains your interest in this area of research? And how do you negotiate or navigate between access and the institutional structures that support such projects?

I often seek out projects which have the potential to help me expand on specific ideas and keep transnational connections in play. Both these projects have museum collections at the heart of their focus. For my own part, I have used them to explore the way in which, as an artist, I might think through questions around representation, repatriation and forms of re-visiting and re-use. Early on in my practice, I had the opportunity to work in the archives of the Empire and Commonwealth Museum. This was a commission with Picture This, a moving image agency based in Bristol, UK. The amazing thing about the commission was that the organisation was able to develop a partnership approach with the museum, which gave me unprecedented access to its archival materials. Although I still had to go through the paperwork of getting permissions and licenses to use the material, the initial hurdle of getting through the door was done away with. Their interest in having an artist come in to work with their material also led to the archivist being extremely open and helpful.

The Transforming Collections: Reimagining Art, Nation and Heritage project has also worked a little like this. As a project partner, the Tate was able to give me access to its collections data. They also assisted with cleaning the data and selecting specific Southeast Asian materials in the collections. In addition, they made it possible for me to film in the galleries. However, I still needed to get specific permissions from the copyright holders of certain works which the Tate was unable to do for me.

Chocolate casts for Sour Kana (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.

What do you think has been/is your purpose? Has your purpose remained steadfast or evolved over the years?

This is a pretty existential question! I am not sure I have ever considered what my “purpose” as an artist has been as such. But what I enjoy the most is that this activity offers me opportunities to engage in ways other jobs might not. I often work with a sense of being positioned outside of disciplinary boundaries, institutions, or national/cultural boundaries. I hold onto this outsider as a way of finding a critical position from which to approach from. Each project starts with me figuring out where I might stand, and how to not overly determine my response so as to produce a space that is evasive.

I am interested in indeterminacy, and recognise this position requires effort. For me, the “purpose” of my work is not to explain; to push back on desires for closure and immediate significance; to challenge not just knowledge, but the process in how “knowledge” might come about. I see my work as a kind of un-anchoring, a letting loose, destabilising over-determined constructions of truth, history, knowledge. This is not my purpose as such, but more a choice in how I try to make work and think about an audience.

I see my work as a kind of un-anchoring, a letting loose, destabilising over-determined constructions of truth, history, knowledge.

And finally, what would be a key piece of advice to young art practitioners? What has been a way of working, a certain kind of attitude etc. they can learn from to apply to their own careers?

I think being open, curious, following through with ideas, people, and questions is important. For me, it has also been important to recognise the ecology of the art worlds we engage with, and to understand the need and importance of collective work, support and sharing. This might also be why I have ended up as an educator, and why I like trying to find collective ways of working. I am less interested in careers and more interested in what the work does and how the practice supports this. As they say, careers can come and go.

This interview has been edited.