My Own Words: Logics and Leeways

Curatorial Education and Possibilities of the Exhibitionary Form

By Carlos Quijon, Jr.

'My Own Words' is a monthly series which features personal essays by practitioners in the Southeast Asian art community. They deliberate on their locality's present circumstances, articulating observations and challenges in their respective roles.

Carlos Quijon, Jr. Photo taken by Mars Edwenson Briones.

The work of the curatorial addresses a number of urgencies in artistic and discursive production and the making public of art: exhibition-making, research, writing, public programming, methods of display and space design, events planning, project management and coordination, and institutional collaborations, among others. In this sense, curatorial agency is plural and prolific. This makes the trajectories in cultivating a curatorial practice equally diverse, especially in a context where institutional opportunities to be a professional curator are hard to come by. The younger generation of curators in the Philippines come from varied backgrounds: artists, art journalists, critics, activists, academics, teachers, etc. There are a few who do work in museums and galleries, but they are mostly coordinators and managers, who in the development of their careers pursue independent curatorial work.

These varied trajectories inflect the logic of curatorial practice, or what we imagine to be its premises and its aspirations, what it should and can accomplish. Before curating my own exhibitions, I was an art writer, a research and curatorial assistant, and project coordinator for the Philippine Contemporary Art Network, a platform established in 2017. My tasks included supporting research and coordinating exhibitions and publications. I first worked for exhibitions in 2016: as project manager to the Manila iteration of the travelling exhibition ‘Soil and Stones, Souls and Songs’ (September-December 2016) curated by Cosmin Costinas and Inti Guerrero for the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD); and as curatorial coordinator for two exhibitions at the Vargas Museum: ‘Republic’ (September-October 2016), curated by Patrick D. Flores; and, ‘A Matter of Contemplation and Discontent’ (September-November 2016), an exhibition of Romanian artists curated by Anca Verona Mihulet. My approach to curatorial work is informed by these positionalities. While writing foregrounded a singular authorial design, coordination discerned a process wherein the flourishing of multiple intelligences and agencies is vital. I see curatorial work as the choreographing of these agencies in order to create compelling conversations among discourses, artworks, artists, archives, space, modes of display.

I find this discernment also playing out in the pedagogy of the workshop, which is how most curatorial programmes and short courses are designed. In 2015, I attended three curatorial workshops: the inaugural batch of Para Site’s Workshops for Emerging Art Professionals in Hong Kong, the Manila leg of the curatorial workshops of the Independent Curators International, and the Japan Foundation Curatorial Development Workshop at the Vargas Museum in Quezon City. I received my curatorial education and training from these workshops, which are usually week-long intensive courses that involved discussions, talks, and site visits. It is rare for these workshops to translate into actual exhibitions or curatorial projects. My case is a bit different, however, since the first exhibition that I curated was made possible by an exhibition grant from Para Site and Goethe Institut Hong Kong, which I received by way of an open call addressed to the former’s workshop alumni. The workshop format allowed us to rethink and resist the preciousness that we usually ascribe to the exhibition, especially as it is understood as the culmination of curatorial work. It also questioned not only the viability of an exhibition prospect but also the necessity of creating another exhibition. These reconsiderations offer leeways to the curatorial process and logic of practice. The possible outcomes of the curatorial activity is imagined in the widest latitude possible, which may assume the form of a publication, a meeting, a series of screenings, an ongoing research, or even an artist conversation. Different forms and scales of participation are also fleshed out, and disparate agencies are convened. Under these circumstances, social contexts are allowed to flourish and become convivial.

Curators of the ‘Curatorial Development Workshop Exhibitions’ with the workshop mentors at the UP Vargas Museum. From left to right: Cristian Tablazon, Mizuki Takahashi, Pristine de Leon and, Patrick D. Flores. Image courtesy of the Vargas Museum.

The Japan Foundation Curatorial Development Workshop (CDW), organised by the Japan Foundation – Manila and the UP Vargas Museum, is exceptional in this case since its aim, from its call for applications, is to realise a curatorial project from the proposals that it will receive. In 2018, the CDW called out for proposals for a curatorial project related to issues of space. My proposal was one the projects to receive a production grant and comprised the CDW Exhibitions along with four other curatorial projects. One was developed as a research project and another consisted of a series of public programmes, and the other three (including my proposal) were mounted as exhibitions. While each exhibition had its own concept and list of artists, the curators also exchanged artists, asking one artist from another exhibition to create a parasitic work for other exhibitions.

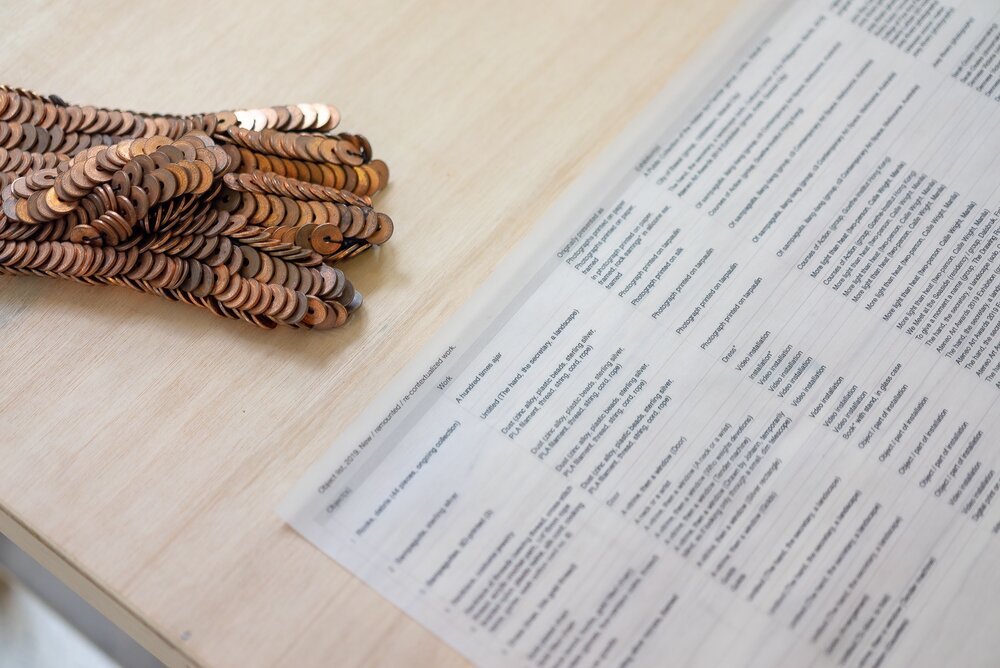

Installation view, Lesley-Anne Cao, ‘Intro, outro, bridge’, 2019, glove made of five centavo coins and a tabular representation of the exhibition and presentation histories of each artwork in the installation. Image courtesy of A.g. De Mesa and the Vargas Museum.

Installation view, Czar Kristoff, ‘Temporary Property’, 2019. In the background: Rocky Cajigan, ‘Epidermis’, 2019. Image courtesy of the Vargas Museum.

Titled ‘a knowing intimacy or a life’, my proposal was interested in looking at the exhibition as a space in which intimacies and vulnerabilities—among artworks, artists, publics, the actual site of the exhibition—proliferated and simultaneously constituted the social life of artistic practice. The exhibition asked artists to not only think about the exhibition as a discrete and bounded phenomenon, but also to consider the exhibitionary form as only one moment in the social life of their practices. Indy Paredes expanded his practice that looks at structures and their aesthetic and social dimensions by creating a work that recreated the museum structure itself. Rocky Cajigan presented part of his ongoing research on the Kadchog Rice Terraces, situated in the northern part of the archipelago, and looked at how site, history, and land inflected questions of identity. Kat Medina for her part problematised the exhibitionary gesture itself and how it relates to her ongoing studies in archaeology, and looked at the material ecology of shells in Philippine culture. This inquiry on how the exhibition exists not as the endpoint of artistic process but as just one moment in the social life of these artists’ practices is furthered by Lee Paje’s and Lesley-Anne Cao’s work. For Paje, the exhibition allowed a recontextualisation of a public installation that she worked on in 2018 and which acquired a different life when put inside the museum for ‘a knowing intimacy’. Cao presented an installation of all the works she created for one entire year of her practice, entangling the singular narration of this one exhibition in the prolific contexts of exhibitions that came before. In all these works, the exhibition is exposed to the vitality of the social life of the artist and their works. It eludes the exhibition’s idealisation as culmination of artistic or curatorial work, and embeds exhibitionary form in the encompassing and evolving notion of artistic practice.

Lee Paje, ‘Pagpamulak’ (Blossoming), 2018-2019, art installation. In the background: Tekla Tamoria, ‘Vegetating Alter/native Histories’, 2019. Image courtesy of A.g. De Mesa and the Vargas Museum.

We can say that this mode of understanding the exhibitionary form leads us to a reconsideration of curatorial activity that shapes but nonetheless resists being tied down to the singularity of the exhibition. The works in the exhibition are ongoing research and continuations of conceptual or artistic interests or are re-presentations of existing works. The curatorial labour involved in the conceptualisation of the exhibition participates in the research and development not just of works for the exhibition, but more so in the development of these practitioners’ artistic trajectories. In this context, we uncouple the curatorial from the exhibition and imagine it as a more expansive set of activities that exceed the parameters of the exhibition and even extend to implicating these artists’ processes and interests in general. The workshop-exhibition framework of the CDW asked proponents to rethink the exhibition as only one of many possibilities for art and research and the making public of art.

This rethinking of the exhibitionary form and curatorial labour finds itself fully fleshed out in CDW exhibitions for 2021. Titled ‘Proto/Para: Rethinking Curatorial Work’ (February-April 2021), the exhibitions were curated by members of PCAN and the exhibition grantees chosen from the cohort of the 2020 workshop, which was conducted online in December.

Faced with the shifting contexts of artistic production and exhibition-making during the pandemic, ‘Proto/Para’ is an apt signpost of the trajectories of curatorial practice in the unprecedented milieu of the pandemic, where we have been forced to reconsider the very logic and recognise the limit of physical exhibitions. The programme involves an acknowledgement of how both the prospect of curatorial education through the workshop method and the curatorial form itself would have to change given the challenges of the pandemic.

The prefixes proto- and para- expands what we imagine as the possibilities of curatorial work. While we typically imagine curatorial labour to culminate in an exhibition, ‘Proto/Para’ insists on the practice’s mutability and malleability and how it can productively transform itself in response to pragmatic constraints that in the context of the pandemic have shifted how we imagine the outcomes of curatorial work, such as the physical exhibition and the actual gathering of people and things in place. The decision to then question the logic of the curatorial process is apropos, since most projects post-pandemic had simplified the question of the persistence of the curatorial activity by way of its migration to digital contexts, such as producing online exhibitions. In doing so, the exhibition revisits the agency of the curatorial and the curatorial capacity to convene sensible socialites is allowed to take—not just for an exhibition sited in a physical space to happen but also, as Patrick Flores has theorised, how “art and curation can generate their own context,” which spans not only the exhibition itself but also curatorial premises, methods, processes, priorities, and even materials.

Installation view, ‘Nena Saguil: Interviews’. Nena Saguil, ‘A Sunken Japanese Ship at Manila’, 1945, oil painting. Nick Deocampo. ‘Adieu Philippines’, 1981, video. Image courtesy of the Vargas Museum.

In relation to the prefix “proto-,” how do we imagine the curatorial activity to render the exhibition inchoate and formative, or how its logic may become generative of contexts and responsive to whatever resources are on hand? In relation to the prefix “para-,” how can it trouble the ideation of the exhibition as a singular and conclusive event in the life of the artwork or the making public of art? In ‘Proto/Para’, rather than constituting the exhibition as a discrete and finished object, the curatorial proliferates sites and modes of participation and making art public. Against the discrete site and situation of the physical exhibition, ‘Proto/Para’ points towards contact zones beyond the actual exhibition where art and its public meet. Aside from on-site exhibitions, we see this in aspects of research and programming, such as in Flores’s presentation of different interviews with the non-objective painter Nena Saguil, or in PCAN coordinator Renan Laru-an’s project that looks at “morphologies and odysseys of attention” by way of online and offline screening programmes, or CDW cohort Carla Gamalinda’s project that mines the interactive potential of the digital medium, encouraging hypertextual annotations of the poetry of Filipino writer Carlos Bulosan.

“The curatorial, because it bears the burden of the social life of knowledges, forms, and practices, thrives in having faith in the ways in which it can create new contexts for gathering art, its contexts, and its publics in situations where these aspects become interactive and intimate, presenting situations of compelling conviviality. ”

I think the vital lesson in the workshop-exhibition format is the accountability of curators to the choices that they make, the iterability of the curatorial project, and the potency of curatorial agency to respond or address its historical milieu and even intervene. These are things that delay the ease with which we imagine the exhibitionary as the most compelling or most logical outcome of curatorial labor. Here we fulfill the expansive and exuberant potential of the curatorial as an activity in which art creates context for itself or becomes, for theorist Irit Rogoff, “an opportunity to ‘unbound’ the work from all of those categories and practices that limit its ability to explore that which we do not yet know or that which is not yet a subject in the world.” The curatorial, because it bears the burden of the social life of knowledges, forms, and practices, thrives in having faith in the ways in which it can create new contexts for gathering art, its contexts, and its publics in situations where these aspects become interactive and intimate, presenting situations of compelling conviviality.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of A&M.

Read all My Own Words essays here.

About the Author

Carlos Quijon, Jr. is a critic and curator based in Manila. He publishes criticism in Artforum. Together with Kathleen Ditzig, he co-curated ‘In Our Best Interests: Afro-Southeast Asian Affinities during a Cold War’ at the ADM Gallery earlier this year.