Why Have Artists Started Independent Spaces and Galleries?

Collectives and artist-curators in Southeast Asia

Coda Culture: Opening Party Show!, 2020, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Coda Culture.

Artist-run spaces are usually considered alternative spaces that exist outside of institutional demands and market forces. In his essay Whither Artists Spaces, Singaporean artist Jason Wee, who founded Grey Projects, wrote: "The more space artists make, the more space there is. Not only for objects (which museums and galleries always make room for), but for artists as well."

It is important to be reminded of their vital contribution to the art ecosystem today, against the backdrop of a growing number of museums in Southeast Asia and increasing visibility of its market. Artist-founded galleries are interfaces between producers and their publics. They are often the places where groundbreaking new work is developed and young artists have their first exhibitions. In my interviews with artists, I am drawn to individuals who are making an impact through not only their studio practices, but parallel activities as curators and gallerists too. The spaces they create celebrate a spirit of self-organisation, community-building and entrepreneurship

This article focuses on artist-founded spaces in Southeast Asia, examining their roles historically, the circumstances around their establishment and the impact running a gallery on the founder's artistic practice.

Nha San Studio.

The emergence of artist collectives in the 1980s and 1990s is an important facet to the development of contemporary art in Southeast Asia. Existing on the margins, the spaces where they exhibited were studios or private homes. Returning to Singapore after spending 10 years in London, Tang Da Wu founded The Artist Village (TAV) in 1988 in a 1.6 hectare kampong space provided rent-free by his relative. At its peak, The Village housed up to 80 artists and organised seven art shows a year.

Arising from similar conditions, Nha San Studio (1998-2010) was founded by artists Nguyen Manh Duc and Tran Luong in Manh Duc's home. It was the first experimental art space in Hanoi that nurtured a generation of avant-garde Vietnamese artists. This spirit of creativity and freedom lived on after the studio's closure through Nha San Collective (2013-present), which is run by a group of young artists. TAV's impact is also seen through galleries founded by early members, such as Vincent Leow and Yvonne Lee's Plastique Kinetic Worms (1998-2008) and Jeremy Hiah's Your Mother Gallery (2004-present).

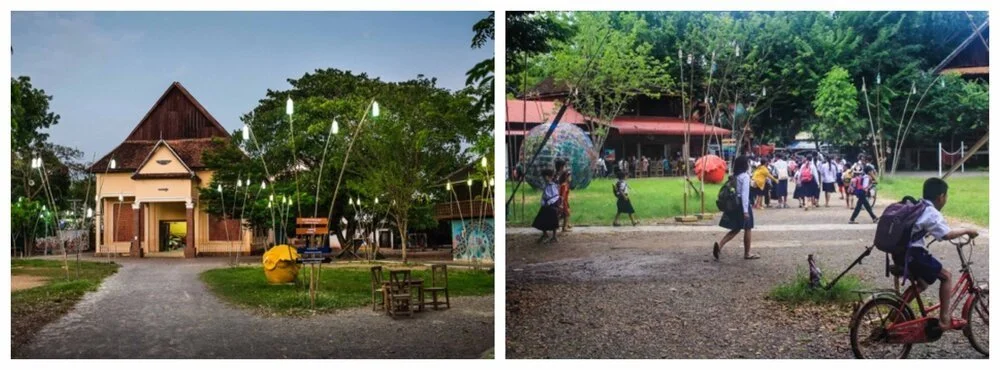

Archival photo of Phare Ponleu Selpak co-founders taken in 1994 during a flood in Battambang. Image courtesy of Phare Ponleu Selpak.

Phare Ponleu Selpak campus. Image courtesy of Phare Ponleu Selpak.

Yet, the contribution of foreign artists is of no less importance. This is evident in Cambodia, where the National Museum was founded by French painter, historian and architect George Groslier. He was responsible for popularising the arts and culture of the Khmer Empire, and also installed Cambodian teachers at the School of Cambodian Arts to train future generations of artists.

Sparking social change through creativity, Phare Ponleu Selpak is an arts school in Battambang started by nine Cambodian art students and their French art teacher Veronique Decrop in 1994. Its name, which translates to mean "Brightness of the Arts" in Khmer, reflects the hope that art brought to its co-founders as children of refugees. Between 1986 and 1992, Decrop provided them with art therapy lessons at the Site Two camp on the Cambodian-Thai border and was a key figure in establishing the centre.

In recent times, Phare opened Rommet Gallery (2013-2015) to promote the work of its graduates in the capital Phnom Penh, such as Chea Sereyroth. The Battambang Circus was also highlighted in the 2019 Singapore Biennale. Today, co-founders Khuon Det, Srey Bandaul, Thor Vutha and Lon Lao continue to manage Phare's activities, while Svay Sareth has left the school to focus on his artistic career which has made waves internationally. Phare's legacy affirms Battambang's position as a cultural capital and a bloodline of Cambodian contemporary art.

Uten Mahamid, the first artist who exhibited at Angkrit Gallery Chiang Rai, with gallery founder Angkrit Ajchariyasophon. The photo was taken just after they finished painting the walls and installing lights in the space. Image courtesy of Angkrit Ajchariyasophon.

Parallel to the growth of communities around artist-led venues is the rise of some of their founders as curators and organisers. Angkrit Ajchariyasophon of Angkrit Gallery (2008-2016) and ARTIST+RUN (2016-present) gained prominence for the exhibitions at his eponymous gallery and was invited to curate high-profile exhibitions such as Chiang Mai Now! (2011, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre) and the 2013 Singapore Biennale. However, he does not distinguish among the roles of artist, curator and gallerist. "Art will never exist without people," Angkrit remarks. What matters most are the relationships around an art space. He thinks of running the gallery as a type of artistic practice as well as a platform to be shared with his artist friends.

Koh Nguang How and Jason Wee installing the exhibition The Past and Coming Melt (2019). Image courtesy of Grey Projects.

Koh Nguang How, The Past and Coming Melt, 2019, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Grey Projects.

For Jason Wee, Grey Projects (2008-present) has given him time to develop his thinking about curating outside of conventional approaches that might have consolidated within paradigms of a museum or state gallery. Reflecting on his experience this far, he asserts, "I remain very curious in the possibilities of curating as an extension of the proximities between artist and artist, and in this way thinking of exhibition-making as an outflow of friendship or solidarity or the rapprochement between two epistemologies or two art practices." Wee believes historicisation is not reserved for institutions, and this attitude inspired two presentations that draw attention to under-documented moments in Singapore art history: Tints and Dispositions (2017), a recontextualisation of Gilles Massot's first photography exhibition in 1985; and The Past and Coming Melt (2019) which situates Koh Nguang How as a pioneer of environmentally-engaged art.

Sa Sa Art Projects artistic director Lyno Vuth speaking at the opening of Interface (2020), an exhibition by XEM collective. Image courtesy of Sa Sa Art Projects.

Artist Clare McCracken's LED workshop with young students of AZIZA school, conducted as part of Sa Sa Art Project's Pisaot residency in the White Building. Image courtesy of Sa Sa Art Projects.

In the absence of institutions tasked with researching and preserving visual culture, artist-run initiatives pick up the baton to create archives. Sa Sa Art Projects (2010-present), founded by the collective Stiev Selapak, operated in Phnom Penh's historic White Building until 2017. It was a piece of modernist architecture from the 1960s which housed vibrant creative communities. Utilising resources and spaces in the neighbourhood, the collective has created art and experiences that evolved with the community's needs such as children art classes and performance festivals. Sa Sa Art Project's White Building Archive and artworks by co-founders Khvay Samnang, Lim Sokchanlina and Vuth Lyno set within the premise are imbued with greater significance since the apartment complex was demolished for redevelopment.

In addition to its community engagement, Stiev Selapak collaborated with curator Erin Gleeson to establish SA SA BASSAC (2011-2018), a gallery and resource centre. Today, Sa Sa Art Projects focuses on working with young Cambodian artists and art graduates, while building deeper connections with artists in Asia through its residency programme and collaborative projects. It remains the only not-for-profit artist-run space in Phnom Penh dedicated to experimental practices.

Jirat Prasertsup, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Torlarp Larpjaroensook at Apichatpong's exhibition Almost Fiction. Image courtesy of Gallery Seescape.

Torlarp Larpjaroensook, 3147966 Mobile Gallery, 2009. Image courtesy of the artist.

Discussing the impact of running a gallery on his artistic practice, Seelan Palay says that he is glad to commit time to Coda Culture in Singapore (2018-present) as it allows the creations of others to be shared and understood. "It hasn't changed the approach and goals of my practice, though it has definitely had an effect on the pace I can work at," he elaborates. "However, I don't see this as a problem as I'd rather take my time to have one clear output a year even if it's a single work."

Torlarp Larpjaroensook takes a different view on the matter and considers Gallery Seescape in Chiang Mai (2008-present) as part of his artistic production. In its early days, the artist's hand and aesthetic is evident from the design and construction of space, to objects in its café and art shop. Gallery Seescape has since evolved from being an open-air alternative exhibition space into a fixture in the city’s art scene, featuring new voices alongside recognised artists such as Apichatpong Weerasetakul, Piyarat Piyapongwiwat and Kawita Vatanajyankur. "I was taught that art is not only for myself but that it needs to be shared with the community," he explains. "So I imagine this place as an easy space for people to meet and exchange their stories. This space is alive, a living gallery."

Blurring the boundaries of art and life, Torlarp has found a way to bring art on the road with 3147966 (2009), a mobile gallery made from a converted car. For his solo exhibition In progress (2012), he created trompe-l'oeil reproductions of objects and tools from Gallery Seescape and staged them among his paintings. The life of objects and how artworks interact in the world are central concerns in Torlarp’s activities as a maker, curator and gallerist.

Artists and their creations at My Toys (2018), Titikmerah Gallery at Publika. Image courtesy of Titikmerah Collective.

Returning to Wee's reflection in the beginning, the fundamental reason for artists to start their galleries is to "make space", whether it is one for free expression and experimentation like those created by the artistic avant-garde in Southeast Asia or places for community engagement and social change. Even though the art world has expanded more than before, hierarchies persist, and an independent platform might be the only way for outsider artists to break into the scene.

Rather than relying on the gallery representation system, Malaysian self-taught artists Ajim Juxta, Latif Maulan and Adeputra Masri worked together as TitikMerah collective (2014-present) to set up a space for exhibiting and selling their works. "At first, we weren't getting traction from the mainstream art scene, especially those who graduated from art schools," Ajim shares. "But after collaborating with younger art enthusiasts, street artists and other collectives, we began to gain recognition and received opportunities to produce public art projects and curate exhibitions." Through innovative exhibitions such as My Toys (2018) and Tun M Custom Show (2019), Titikmerah draws in diverse audiences and brings a fresh perspective to the Kuala Lumpur art scene.

Despite the positive contributions offered by such spaces, it must be emphasised that they put additional financial stress on the shoulders of artists. Rental and costs associated with exhibition production are often shared among co-founders or participating artists, as is the case for TitikMerah collective. The next article on artist-founded galleries in Southeast Asia delves deeper into the economics of running these spaces and potential models for long-term sustainability.