Fresh Face: Nat Setthana

Speculating future through photographic installation

A&M's Fresh Face is where we profile an emerging artist from the region every month and speak to them about how they kick-started their career, how they continue to sustain their practice and what drives them as artists.

Artist Nat Setthana at 100 Tonson Foundation. Photos by Preecha Pattaraumpornchai. Image courtesy of 100 Tonson Foundation and the Artist.

Born into a city layered with visual cultures, Bangkok-based artist Nat Setthana took an early interest in using his camera to explore urban landscapes, particularly sites that bear the impact of socio-political shift and commercial gentrification. For him, photography becomes a magical tool that allows him to capture moments of transition and revisit sites to discover hidden things that he has overlooked. Combining his photographic curiosity with an interest in creating site-specific installations, Setthana has experimented with projects that incorporate found elements within a space to excavate, and sometimes bend, its intertwining narratives.

Setthana’s first solo show Photopsia (2024-25) at 100 Tonson Foundation marks a significant turn in his conceptual figuration of photography, as he decides to shift his focus on it as a medium to that of a subject. Unpacking the basics of photography, namely projection and perception, he transforms the two exhibition rooms at 100 Tonson into two contrasting realms. One resembles a camera’s black box where the passage of time and light is recorded through a video showing a fabric’s fluttering movement. The other is a blinding white void-space, where overexposure to light triggers photopsia and visual distortion of depth. The artist explores optical disturbance as an experiential medium in space, where one can freely imagine the infinite potentials embedded in an image.

Nat Setthana, Photopsia, 2024, site-specific installation, quartz, cyclorama room, light, and warning text, variable dimensions. Photo by Preecha Pattaraumpornchai. Image courtesy of 100 Tonson Foundation and the artist.

Nat Setthana, Photopsia, 2024, site-specific installation, quartz, cyclorama room, light, and warning text, variable dimensions. Photo by Preecha Pattaraumpornchai. Image courtesy of 100 Tonson Foundation and the artist.

The white room, inundated with intense white light, thus undergoes an architectural transformation to create Setthana’s desired visual effect. Inspired by the ambience of a photography studio, where emptiness signifies a sense of becoming, the artist tweaks the space’s components to disrupt its boundaries. Eradicating corners and repainting the room in a stark white colour, Setthana creates a site of optical illusion, where its ceiling, walls, and floor seem to meld together, resulting in an endless terra infirma. This void becomes a metaphoric backdrop for thought projection and idea contemplation, which alludes to photography’s function of visualisation and future-figuring.

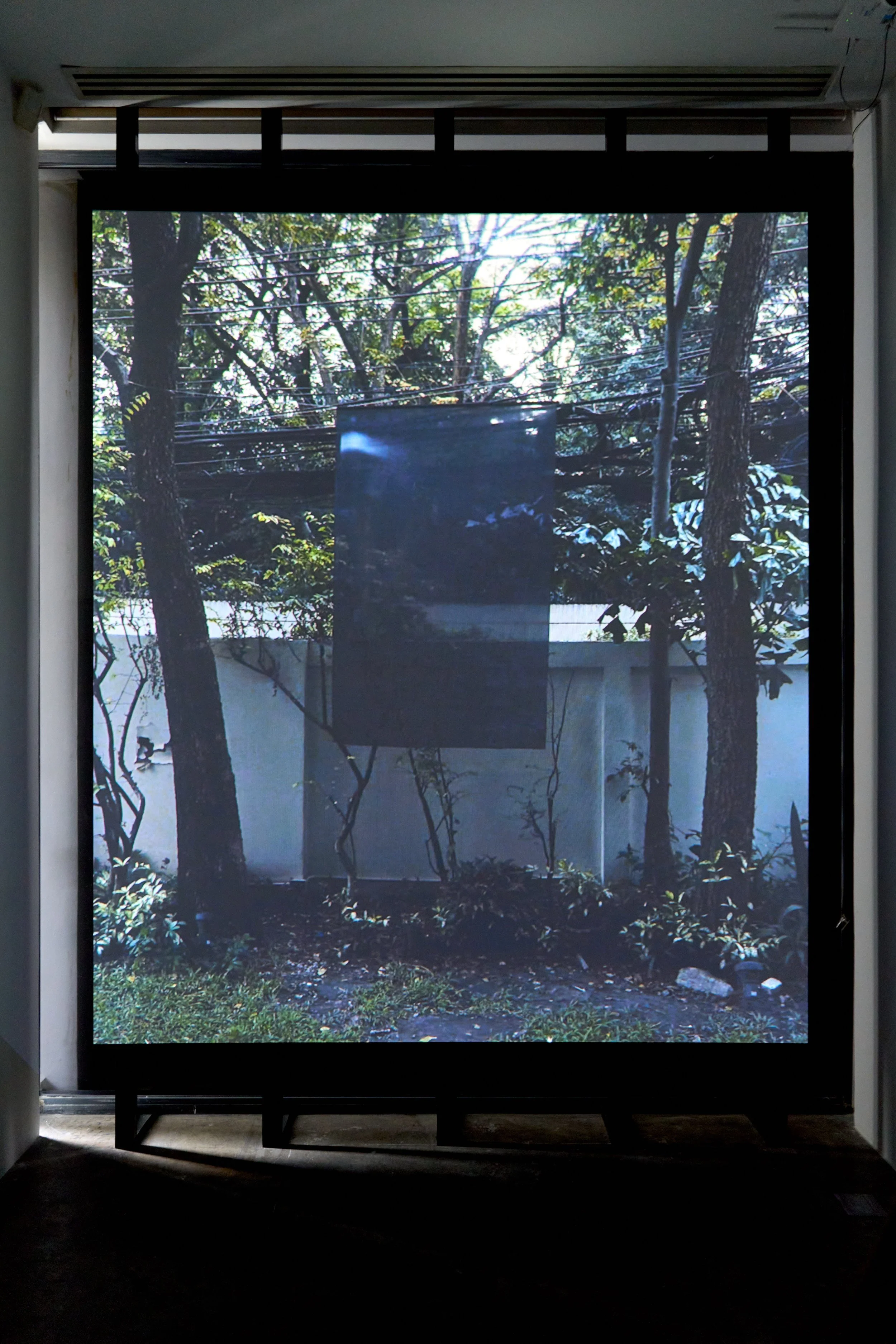

Nat Setthana, Rendering of thin air (100 Tonson Foundation), 2024, site-specific video installation. 1-channel video projecting on wooden screen with black glass, 51 min 45 sec, H 358 x D 26.5 x W 292cm. Photo by Preecha Pattaraumpornchai. Image courtesy of 100 Tonson Foundation and the artist.

Transiting to the black room, which serves as 100 Tonson’s library, Setthana sets up a projection of his video, in which he recorded the movement of sunlight and a hung piece of fabric through the library’s window. As the scenery on screen transitions from pitch darkness to gradual illumination, the fabric continues to flutter in latency, undulating with the movement of air and time. Once more, Setthana draws references from the physical darkroom as well as the etymology camera obscura to gesture toward photography’s time-bending power. The physical transition between these two rooms also resembles the tension between dark and light, that colours not only the technology but also the philosophy behind photography. Setthana’s chiaroscuro installation thus presents a deconstructive way through which photography can be unpacked through space, light, and projection.

Interview

Artist Nat Setthana at 100 Tonson Foundation. Photo by Preecha Pattaraumpornchai. Image courtesy of 100 Tonson Foundation and the artist.

You graduated from the School of Architecture and Design, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, and are currently pursuing a Master’s Degree at Aalto University in Helsinki, Finland. How have your educational experiences shaped your artistic practice and conceptual development?

I graduated from King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi with a Bachelor’s degree in Communication Design, and a Master’s degree in Visual Communication. The key takeaway of the programme is to convey our ideas across a wide range of media. As you know, Bangkok and Southeast Asia are very rich in visual material, so I am constantly inspired by exploring things and sites across the city. While doing field research for my coursework, I would take photographs of the urban landscapes so I could revisit them afterward. Also, whenever I looked at photos of different sites, I would notice something that I had previously overlooked! Photography has thus become an act of pondering for me. That is why I chose to pursue photography for my second Master’s at Aalto. I wanted to unpack various conceptual aspects of photography and deepen my understanding of this medium.

Nat Setthana, Exposed Identity, 2018, installation view at Bangkok University Gallery in the group exhibition, Treasure (2023). Photo by Atit Sornsongkram. Image courtesy of the artist.

Most of your art projects utilise photography as a medium through which you dismantle complex matters such as the borderline between personal and collective histories, or the traditions of cinematic presentation. How do you define your photography practice?

My photographic practice is about the act of revisiting and deconstructing. I use photography as an attempt to deconstruct the subject of inquiry. To me, the magic of photography is to freeze the subject and manipulate time, and in doing so, it crops the subject out of its original context.

To put this in perspective, let’s use the project Exposed Identity (2018) as an example. In that project, I reexamine the Bangkok Station, also known as Hua Lamphong through photography. I visited the place time and time again, and every time I did, I took at least one roll of film. In the process, I managed to dismantle the whole space, cutting it into many pieces. The process of deconstructing comes full circle when I present the work with two running slide projectors, where the photographs are flashed for a split second, leaving spectators with fleeting afterimages.

My photographic practice always incorporates the viewer in the process. To me, photography is an active event enabled by the spectator, a role that I also inhabit. It is the interaction between light and the point of contact that makes photography possible. Photography is as much an experiential process as it is an act of image-making.

“To me, the magic of photography is to freeze the subject and manipulate time, and in doing so, it crops the subject out of its original context.”

Nat Setthana, Sunsetless, 2020, installation view at So Heng Tai Mansion, as part of Bangkok Design Week #Diverscity 2020. Photo by Jom Triratnarong. Image courtesy of the artist and the Yeast Team.

You also co-founded Yeast, a multimedia design team practicing in experiential design and immersive installations. In what ways have your projects with Yeast informed your photographic practice?

I was a fresh graduate in 2018 when I co-founded Yeast with a group of friends. While it is a means for us to make a living, we are all interested in site-specific installations, especially with light and sound. One time, during Bangkok Design Week in 2020, we were given access to an old scuba diving school. While the city constantly shifts, the school’s architecture remains intact, almost frozen in time. This prompted us to think of the sun and its constant presence. Also, the school was close to the bank of Phraya River, so its location also inspired us to create an installation titled Sunsetless (2020) that evokes the sun setting in the middle of the pool! That is how we make work, creating concepts based on site-specific elements.

Nat Setthana, Photopsia’ 2024, site-specific installation, quartz, cyclorama room, light, and warning text, variable dimensions. Photo by Preecha Pattaraumpornchai. Image courtesy of 100 Tonson Foundation and the artist.

In your debut solo exhibition Photopsia at 100 Tonson Foundation, you focused on unpacking photography as a subject, by playing with elements of projection such as light, depth, and space. What caused you to shift from engaging with photography as a medium to a subject?

For my first solo show, I want to create a site-specific installation that explores the idea of photography without context. A photograph rarely exists without context, as we tend to read it through the lens of personal experience. But what about a photo that is detached from existing contexts, that figures the future instead of capturing the past? I am intrigued by the term “visualisation” in photography theory. Coined by landscape photographer Ansel Adams, visualisation refers to the unfolding of potentiality, the future photograph so to speak. It represents a mode of photography that is not confined to the past but is instead an act of creating the future. To me, this concept is about the act of imagination and about finding a way to bring that envisioned future into reality.

I am also inspired by the photography studio itself, a decontextualised white room to project ideas and construct images. I decided to play with the architecture of the main exhibition room at 100 Tonson by covering its corners to give the feeling that the floor, ceiling, and walls are melded together. Saturated with high-intensity light used in studios, the room appears borderless, a smooth whiteness that triggers spatial disturbance for viewers. To me, this sense of visual uncertainty signifies photography’s destabilising, thus future-making capacity.

For the smaller library room, I showed a video projection that documents sunlight movement, from complete darkness to clear images. This slow visual unfurling not only captures time, but also resembles the process of developing photos in a dark room. The transition from darkness to brightness between the two rooms also resembles a camera’s internal structure. If you open the lens cap, you allow light to fill into the dark room inside the camera. This switch is too quick for our eyes to capture, and it also plays with the notion of absence and presence.

Can you name some artists or photographers who have left an impression in your artistic practice?

I am drawn to the work of Berenice Abbott, a photographer known for her documentation of New York City’s transformation in the 1920s and 1930s. I like the way she used the camera to deconstruct the urban landscape, in which she captured the transitions happening at specific sites due to gentrification—something that I am also interested in. I like the idea of comparing what a place is and what it used to be, which also speculates about what might become of the place. Urban photography thus can trigger our imagination of different versions of the future.

Are there any upcoming exhibitions/projects that you would like to share?

I have two group exhibitions to share. The first is my graduation show Masters of Photography 2025 – Image Being at the Finnish Museum of Photography which runs from 31 January to 20 April 2025. The other one will take place at Bangkok Kunsthalle around June this year, as part of their open call.

Nat Setthana’s solo show, Photopsia at 100 Tonson Foundation is on view from 19 December 2024 to 6 April 2025.