Fresh Face: Marisa Srijunpleang

Archiving memory along Thai-Cambodian borderlands

A&M's Fresh Face is where we profile an emerging artist from the region every month and speak to them about how they kick-started their career, how they continue to sustain their practice and what drives them as artists.

Marisa Srijunpleang.

Born in 1993 in Surin on the Thai-Cambodian border, Marisa Srijunpleang examines lives shaped by displacement and contested boundaries. The Bangkok-based artist graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Sculpture from King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang in 2017. Her practice has garnered recognition, including a residency at the Singapore Art Museum in 2025 and a fellowship with The Alternative Art School in 2024. Marisa presented her first solo exhibition Bloom with the Wind Blows (2024) at HOP – Hub of Photography in Bangkok, and has participated in group exhibitions in South Korea and Japan.

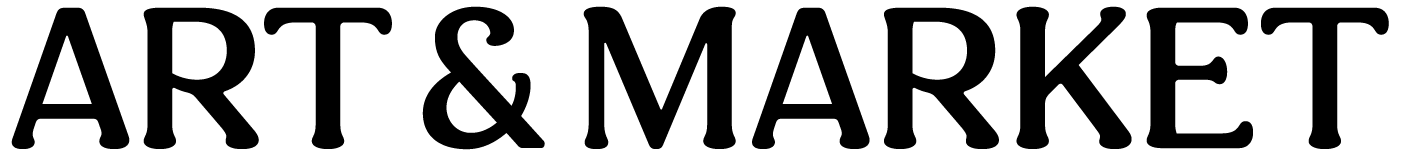

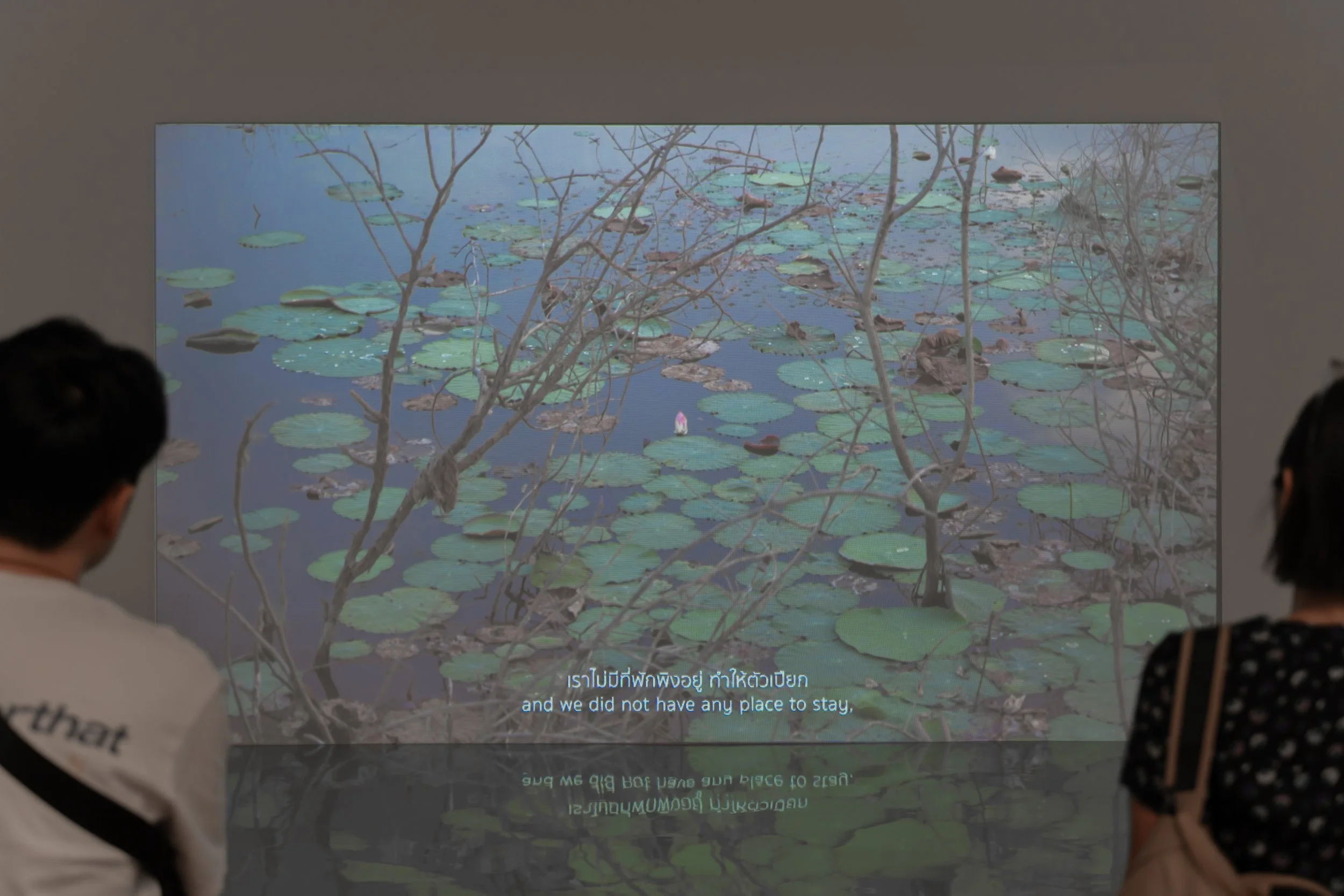

Marisa Srijunpleang, T360174, 2023, video installation view, exhibited In a cogitation, Early Year Project #6, Bangkok Art and Culture Center (BACC), Bangkok, Thailand. Image courtesy of Marisa Srijunpleang.

Marisa’s methodology centres on collaborative documentation and material gathering. The video installation T360174 (2023), which emerged from her exploration of histories along the Thai-Cambodian border, was drawn from both personal experience and disappearing family narratives. It was exhibited at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, and featured elements from the San Don Ta (Sart Khmer) ceremony, a Thai-Cambodian ancestral tradition. The project takes its title from her aunt’s registration number during refugee processing to the United States of America (USA). The 16-minute single-channel video at the heart of T360174 combines six elements: Marisa’s mother speaking about her grandmother, footage of grass and flowers along the Thai-Cambodian border, an aunt recounting wartime experiences, family members dyeing fabrics using methods from the war period to create the flower sculptures in the exhibit, documentation of the San Don Ta ritual honouring the dead, and recordings of Jariang, the traditional Cambodian singing Marisa’s grandmother performed before the war. These six elements build a composite archive that anchors individual grief within the wider historical ruptures of war.

Marisa Srijunpleang, Bloom with the Wind Blows, 2024, crown flower seed on flat acrylic, 60x60x45 cm. Image courtesy of HOP - Hub Of Photography.

The search for a missing flower used in the San Don Ta ritual became the conceptual entry point for Bloom with the Wind Blows (2024). Research into the ritual revealed references to Phka Bayben, described only as a fragrant white grass-like flower that blooms in the 10th lunar month and withers after the ceremony. With no formal botanical identification available, Marisa turned to the landscape itself. She travelled from Surin to Cambodia along routes her family once took as refugees, photographing and collecting dok rak (crown flowers) seeds alongside species such as Little Ironweed (Vernonia cinerea), Coat Buttons (Tridax procumbens), and other wind-dispersed plants commonly seen as weeds growing wild along the Thai-Cambodian border and at former refugee camps. Bloom with the Wind Blows centres on a sculptural work of hundreds of dok rak arranged on a white acrylic base in the form of the traditional Thai-Cambodian floral mound used in ancestral offerings.

Marisa’s practice attends to the landscape’s processes of dispersal and regeneration across borderland ecosystems. She sees them as models for understanding how memory persists across families fragmented by war and borders. Drawing on sculpture, photography, and video as complementary forms of witness, her work functions as intimate family archive and collective record, tending to the rituals, voices, and practices that exist outside official documentation.

Interview

Marisa Srijunpleang, T360174, 2023, a photograph of the artist’s aunt during her refugee resettlement, exhibited In a cogitation, Early Year Project #6, Bangkok Art and Culture Center (BACC), Bangkok, Thailand. Image courtesy of Marisa Srijunpleang.

In 2017, you graduated from King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Sculpture. Could you briefly describe your experience during those formative years, the education you received and the cohort you interacted with?

I had dreamed of living in Bangkok since I was a child. I watched people in my village gradually leave home for the city, and saw relatives return only during holidays. Those moments probably made me feel that one day, I would have to leave home as well. I eventually left my village for university in Bangkok. However, instead of taking me away, my university years slowly brought me back home. By learning various ways of making art, it helped me understand and learn more about the world. It changed my views on many things. Asking questions about where my life and hometown stands in the world became the foundation of my artistic practice. It was meaningful to go through this learning experience alongside friends from different places, as well as teachers who guided us through these questions together. In a way, we all left home to come to Bangkok or to the university in search of something, even though we may not be clear about what awaits us in the city.

Who has been a mentor or an important artistic influence in shaping your practice? And why?

Rungruang Sittirerk is an artist who speaks about people’s lives and labour, and he was also my teacher. I remember the spark in his eyes when he talked about works that inspired him to become an artist. At that time, I did not fully understand what it meant to feel so driven by art that your whole body responds to it. But through our exchanges, I saw how people’s stories can grow, take form, and communicate emotions or messages to the world through art. I like seeing someone else’s work and feeling a sense of quiet excitement to make something of my own too.

What was one important piece of advice you were given that has stayed with you?

This may not be directly about art but for the past 10 years, I have shared my life with my partner, who witnessed every stage of my growth, from being a student, to working, to becoming an artist. From her, I learned how to approach people with empathy and understanding. She taught me not to dwell too deeply on actions that trouble me, especially when they may not come from bad intentions. When something affects me emotionally, I try to accept it, understand it, let it go, or learn to live with it, so I can stay focused on what matters to me. This way of thinking has been essential in a field where I am constantly meeting new people.

Do you make a living completely off being an artist? If not, could you share what other types of work you take on to supplement your income? Do these activities also inform or affect your practice?

In the early years after graduating, I barely made my own work. I spent about five years working as a photographer and an artist assistant before returning to my own practice. It is still very difficult to support myself through art alone. Alongside my artistic work, I continue to earn a living as an artist assistant and photographer, mainly documenting exhibitions for galleries, which remains my main source of income.

Starting my own artistic practice at this stage of my life feels important. Those years gave me time to understand how the Thai art scene functions and to get to know the people working behind the scenes. In many ways, those jobs prepared me to become an artist. I am not sure I could have managed everything if I started making art immediately after graduating.

Marisa Srijunpleang, T360174, 2023, video installation view, exhibited In a cogitation, Early Year Project #6, Bangkok Art and Culture Center (BACC), Bangkok, Thailand. Image courtesy of Marisa Srijunpleang.

What were you investigating or trying to understand through T360174 (2023)?

In this work, I speak as a descendant, asking how I can tell these stories in relation to my family’s experiences of the Cambodian genocide of 1975. The work is shaped through the memories of those who survived: my mother, who cared for my grandmother and her sister’s children after their loss, my aunt who migrated to the USA and other family members who were caught in the war.

I work through memories, conversations, and a desire to mourn ancestors lost to violence. I researched a Khmer-Thai ritual called San Don Ta, an ancestral offering ceremony. During my research, I found references to a flower used in the ritual called Phaka Bai Ben. Yet this flower is recorded only vaguely, without a name. It is described simply as a fragrant white wild flower that blooms around the 10th lunar month and withers once the ritual ends.

The disappearance of this flower became the centre of T360174. Beyond addressing the impact of war through symbolism, the piece insists that such violence should never happen to anyone. By telling personal stories, I hope to connect through shared human feelings, reminding us that those who experience war are someone’s parent or child. I hope that this message can help bring people closer together, or create space for reflection and dialogue.

T360174 also led me to explore the Thai-Cambodian border. I learned how people were connected long before borders existed through language, rituals, and plants. This became an important direction for my later work.

“I work through memories, conversations, and a desire to mourn ancestors lost to violence.”

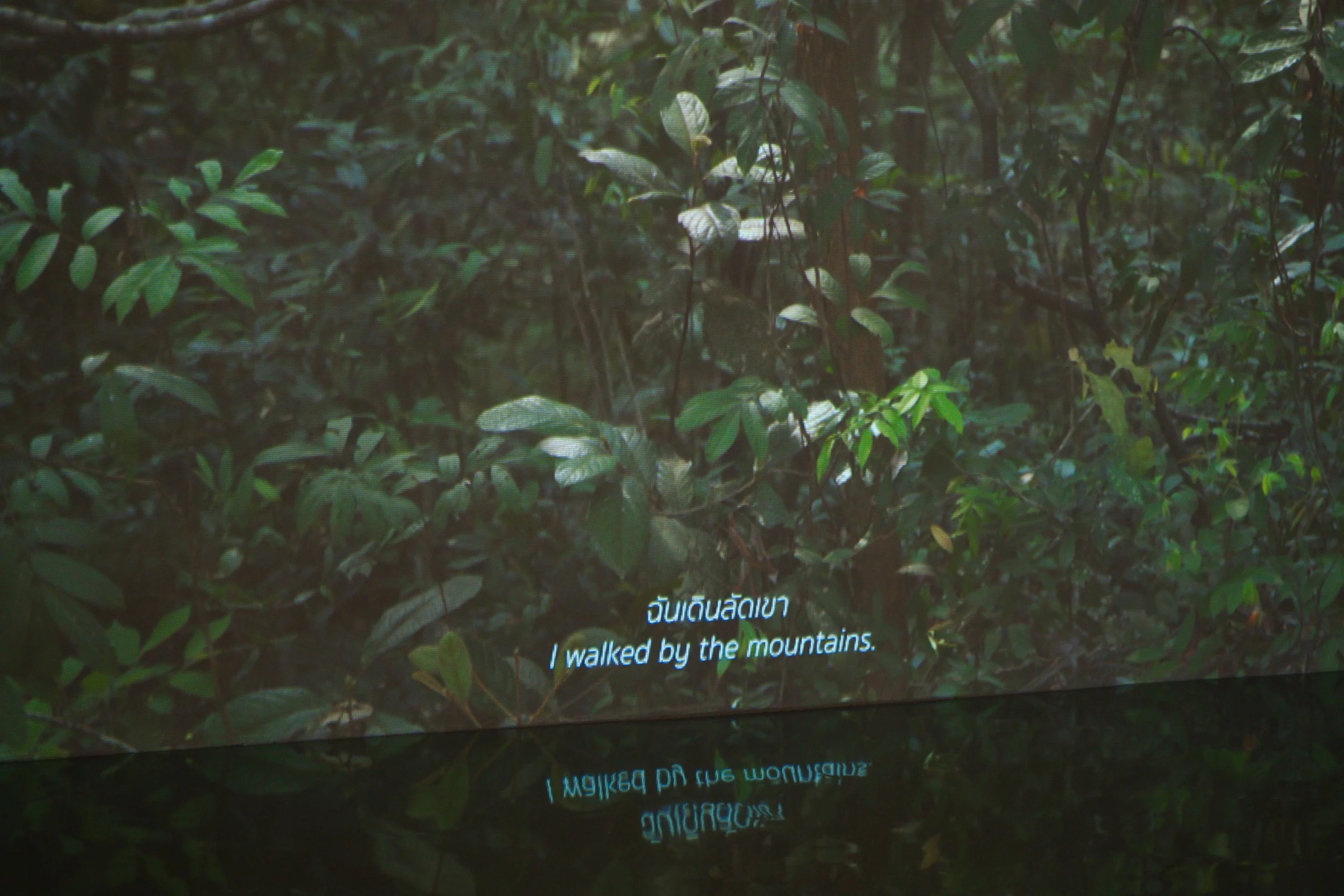

Marisa Srijunpleang, Re Intertwine, 2024, photograph. Image courtesy of the artist.

Marisa Srijunpleang, Grow and Remember me, 2024, photograph, inkjet printing on matte paper with an old frame used to hold a picture of my grandfather, 47.8 × 34.8cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

In 2024, you presented your first solo exhibition, Bloom with wind blows, at the Hub Of Photography (HOP) in Bangkok. The exhibition brought together sculpture, photography, and video, all connected to the landscapes and plant life along the Thai-Cambodian border. How did this opportunity come about? And what were the key themes or ideas you explored through this body of work?

This exhibition began with the conversations with Thiti Teeraworawit, the curator at HOP. He was interested in how I used flowers and landscapes to tell stories in T360174 and suggested that translating this approach into photography could open new possibilities. Bloom with wind blows (2024) speaks about those who have passed away through the search for the missing grass flower, conveying unresolved grief and a reflection on a life that I can only reconstruct through fragments of memory.

The work also addresses those who died because of the war, specifically my grandfather. It became a journey to trace his memory back to his home in Cambodia, along refugee routes between Thailand and Cambodia, and to refugee camps that existed during the war. Through conversations with my mother, I learned that after the war, those who fled Cambodia had to stay in refugee camps. She only learned later that my grandfather died of illness in a refugee camp. This led me to travel to various refugee camps in Thailand. I still remember the feeling of visiting Khao I-Dang refugee camp in Sa Kaeo Province, where I encountered notebooks written by visitors. Some people came to search for family members, some came to remember their time as refugees, and others came to perform ancestral rituals for those who had passed away. Next to these notebooks were lists of names of people who had once lived in the refugee camps in Thailand, kept for those who were still searching for missing family members or acquaintances.

In my travels, I encountered milkweed plants with white seeds that floated through the air with the wind. These seeds reappeared throughout my journey. The process felt as though I was collecting my family’s memories amid abandoned fields and forests.

I paid particular attention to clusters of white grasses, photographing them at the moment when their seeds were about to disperse into the wind. Plants such as little ironweed (Vernonia cinerea), coat buttons (Tridax procumbens) and other grasses appear in this body of work. They are ordinary plants often considered weeds, which spread by floating through the air. To me, it reflected the transmission of memory from one generation to another. Even though I do not know exactly which plant was used in the ritual, the image of white grasses growing together, ready to disperse and take root elsewhere, became an appropriate symbol of fragile and uncertain borderlands.

“They are ordinary plants often considered weeds, which spread by floating through the air. To me, it reflected the transmission of memory from one generation to another.”

The artist’s grandmother’s house in Surin province from 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

You describe documenting activities with your family and community, creating objects during these processes, and incorporating them into your work. How do you navigate the relationship between documentation and participation, between observing and being part of these moments?

I realised that many shared activities were disappearing along with my grandparents’ generation. So the work often starts by initiating simple activities and doing them together with my family and community. I explain what I am doing and keep the conversation open with everyone involved, so the process remains shared and respectful.

I document what happens as it naturally unfolds, showing how we live our lives. Because I am part of the community and grew up there, it feels natural rather than planned. I do not separate myself as an observer. It is almost like writing in a journal about me and my family.

I can never return to the work I did with my community. Those moments existed only then, which allowed me to create the work I did at that exact time. My father, and the neighbours who were like grandparents to me, have since passed away.

Could you share your favourite art space or gallery in Bangkok/ Thailand? Why are you drawn to that space and what does it offer to you or your practice?

Rather than a defined space, what I value most are the conversations I had through my roles as a photographer, assistant, or artist. I cherish discussions with people in the art community who share the same hope that the art scene will grow for everyone.

These community spaces allow me to reflect on my own work and help me reconsider my goals as an artist. I appreciate feedback about my work because it reveals different perspectives that I may not have considered myself.

Coat buttons, mexican daisy, Little ironweed, ash-coloured fleabane, crown flower seed. Image courtesy of Marisa Srijunpleang.

What are your hopes for your own local art scene, and regionally as well?

In recent years, many collectives have emerged across different provinces. People who once moved to Bangkok are beginning to return to work in their hometowns, and younger artists see the possibility of working in their local areas and hometowns. Although there are still some challenges. I see more strength and diversity in these movements. Art is no longer concentrated only in Bangkok, and local narratives are becoming more visible. I hope that artists are able to sustain themselves in the future, even without widespread recognition or market demand. I hope to see more long-term programmes that support people in the art community across different practices, and encourage community-based approaches that open dialogues and exchanges among artists and their audience.

The artist working on sculptural elements in Bloom with the Wind Blows (2024). Image courtesy of the artist.

Are there any upcoming exhibitions or projects that you would like to share?

In 2026, I plan to begin a new project that continues my exploration of the Thai–Cambodian border. This year, people living along the border are facing hardship due to territorial disputes between the two states, leading to displacement, military presence, and loss of life. These things should never happen.

Until now, people still cannot return home and worry about how they will survive without income. I want to explore how art can call attention to these issues, questioning how these imagined borders cause suffering in people’s lives.

This project is still at its early stage. I am interested in exploring the temple as a site often part of the Thai-Cambodia conflict conversation. I want to focus on much smaller elements: plants that survive together within ecosystems, growing on trees and stones, including the stones of the temples themselves. I envision it as a long-term project that will allow me time to conduct field research, study current conflicts, and revisit history. Or at the very least, record and affirm that such violence should not continue.