Fresh Face: Lesley-Anne Cao

On the mutable life of materials

A&M's Fresh Face is where we profile an emerging artist from the region every month and speak to them about how they kick-started their career, how they continue to sustain their practice and what drives them as artists.

Portrait of Lesley-Anne Cao. Photo by Beatrice Cao. Image courtesy of the artist.

Lesley-Anne Cao (b. 1992, Manila) is interested in the material conditions of meaning-making. In her earlier archival work, she redefines what’s worth keeping. A Hundred Times Ajar (2019) constitutes her index of debris: flakes of paint, slivers of tile, vagrant objects gleaned during walks around buildings and parking lots. She photographs them with the formality of museum documentation and arranges them in taxonomic grids. In Arrangement (490 Flowers, 67 A. Mabini) (2020), every flower in her family home since the 1990s appears in one pictorial space. Altogether, 490 photographs were scattered across a vertical white panel, each bloom discrete and legible. Strings of sampaguita buds neighbor dried arrangements. Folded floral fabrics float near a floral-patterned thermos. A book of Emily Dickinson poems sits beside Mga Halamang-Gamot sa Pilipinas (Medicinal Plants in the Philippines) with its bright green botanical cover.

Lesley-Anne Cao, Subtitles or a love poem in plain language (still), 2017/2019, single channel HD video, 8min 52sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

Her text-based work operates differently. In Untitled (When the cup) (2017), she carves an absurd equation into grass at Heping Island Park, Taiwan. The Chinese characters “杯子” (cup) and “鲸鱼” (whale) hover above the English phrase, “when the cup is heavier than the whale,” creating a bilingual riddle, in which the cup and the whale exist in impossible relation to expected properties of heaviness and scale. Subtitles or a Love Poem in Plain Language (2017/2019) is a mute video of analogue black-and-white stills. Each four-second frame pairs text with photographs that do not corroborate one another. One frame shows an interior corner, stairs ascending left, a small framed photograph propped against the wall, while the subtitle reads “the little book I could have made”. No book appears. Another frame: manicured topiary in a park, sculptural and formal, captioned “My father wrote poems”. Then a dense bed of flowers fills the screen, captioned only “Now.” The text moves between intimate declarations and bare temporal markers, while the images offer landscapes, interiors, flora. The viewer must choose whether to trust the language, trust the image, or make meaning from the gap between them.

Lesley-Anne Cao, Amphibian palm, 2024, installation with glass tanks, mirrors, glass weights, digital print on satin, machine embroidery on gazar, waterproof paper, plastic seals from kiat-kiat net bags, acrylic boxes, wave makers, relay timers, water, music ('a watery commons where nobody has to perish' by Itos Ledesma, two channel audio, 41min). Photo by Marian Barro. Image courtesy of the artist.

Through the years, she has returned to the book form obsessively. Dreams of Speaking (Book for Weeds) (2020), employs polytarp sheets, handbound and printed with images of her mother, a plant molecular biology professor, the caretaker of her father’s grave. The book was then left out in the rain and dew and mud, subject to the intrusion of ants and gnats. What was a book becomes an artifact weathered into the landscape. In A Song Plays from Another Room (2021), she creates an aqueous ecosystem: five photobooks printed on waterproof paper float in glass tanks, alongside one constructed from plastic ponkan wrappers with an electronic wave maker that generates currents to jostle its makeshift pages. The following year, Fold, Fall, Drape, Gather, Rip, Wrap, Crease, Cling, Fly (2022) replaced paper with seventy-six pages of digitally printed satin, again submerged in a glass tank, the book becoming textile.

In her latest exploration, Amphibian Palm (2024), Lesley expands on her repertoire of almost-books. Volumes made of satin, gazar, plastic seals from kiat-kiat net bags all floated in mechanised glass tanks labelled: “For fruit,” “For measuring the wind,” “For things that can fold,” “For eternity.” What good is a book that measures wind? What fruit does reading produce? Does eternity mean the book never ends, or the reader never arrives? Where in A Song Plays from Another Room (2021) it was Itos Ledesma’s A fountain of gardens, a well of living waters, and streams that provided the soundtrack, in Amphibian Palm (2024), it’s a different composition titled A watery commons where nobody has to perish, that pervades the room. The shift is ambient and unannounced, but listening carefully, one senses this drift. Each waterlogged page now carries the overtones of larger drownings, meant to evoke Metro Manila’s recurrent floods, Typhoon Yolanda’s catastrophic surge.

As such, her work places categories of archive, documentation, book, language in transformative conditions. Painted debris and petals are photographed and displayed with museum-like formality. Subtitles complicate rather than clarify their images. A cup cannot outweigh a whale, yet it is carved into grass. Books are left out in the rain or survive underwater. The through line is material: the work examines what forms become when their expected functions are suspended.

Interview

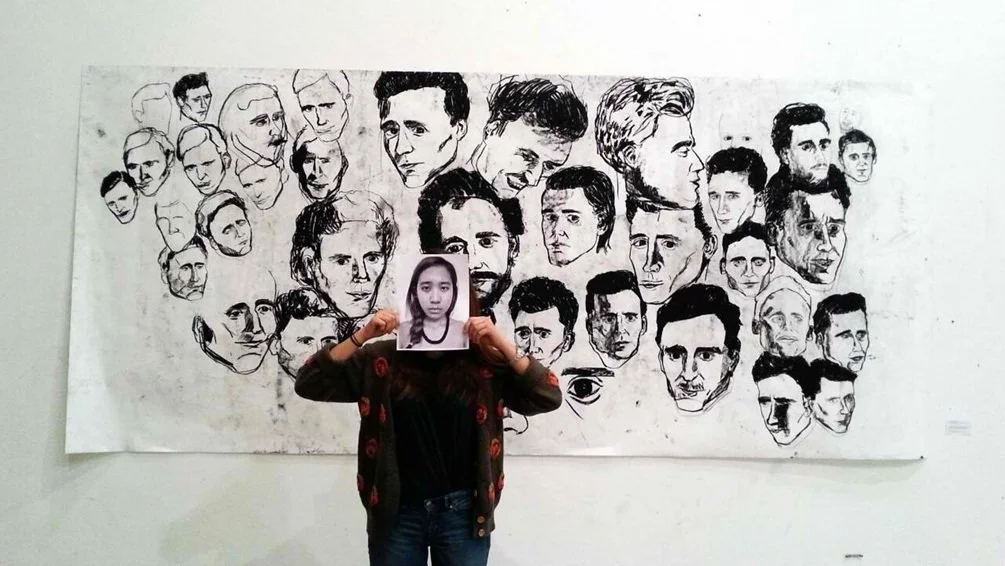

Exchange students' exhibition, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (ENSBA), Paris, 2013. Photo by Dahye Seol. Image courtesy of the artist.

In 2014, you graduated from the University of the Philippines (U.P.), with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting. Could you describe your experience?

I interviewed for the Visual Communications programme and was advised to apply at the Studio Arts department instead. I think my art school foundation manifests in how I enjoy working with what is available and being open to conversations. But I was not sure about being an artist. I arrived at a turning point when a teacher introduced me to the artist Félix González-Torres. My U.P. education also encouraged interests in different disciplines like linguistics, sociology, natural sciences, and world literatures.

Through a partnership with my college, I received a fully funded scholarship for a semester at École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (ENSBA), in Paris and travelled as much as my stipend allowed. This experience expanded my worldview. I encountered other approaches to art education, artists from different contexts, and various ways of presenting and encountering work. I also realised that I want to explore these learnings further with a practice situated in the Philippines.

Who has been a mentor or an important artistic influence? And why?

Gary-Ross Pastrana and Lani Maestro. I see them as poets and storytellers. From their works, I learnt that what seems to be simple can also be expansive, affecting, complex, and playful. They have also been encouraging co-conspirators. They engage with young artists in a non-hierarchical way.

Gary is one of the first artists I worked for as a project assistant after I graduated and he was curator for some of my early group shows. As a curator, he is curious alongside the artists, and is involved in the exploration that goes into exhibition-making.

What was one important piece of advice you were given?

This is something I am still learning but finding increasingly necessary in order to take care of myself and my work: That we can say no. That we can step back if we need to. That we can say we do not know or do not know yet. To recognise and practise pauses and refusals when possible, necessary, and well-thought-out. This is both a privilege and a responsibility.

Do you make a living completely off being an artist? If not, could you share what other types of work you take on to supplement your income? Do these activities also inform/ affect your practice?

I had previously taken on gigs assisting other artists and writing. But for over a year now, I have had to focus on successive projects and care work. I am lucky I have saved up a bit, and that I can live with my family. Some of my recent projects had production funding or artist fees, something I acknowledge is uncommon here. I also worked as a remote researcher for Asia Art Archive Hong Kong until 2023. Working on others’ projects and with archives continues to inform my inquiries into the life of materials in relation to communities, institutions, and natural/environmental forces, in ways both conceptual and practical.

Where I live largely dictates my work. I do not have a studio and work in whatever space is available at home. It is important for me to have a fluid practice involving iteration and continuity: working with a central idea, and shaping everything else, whether practical and conceptual, to what resources are available.

Lesley-Anne Cao, If time is an arrow, what is its target (detail), 2023, installation with coconut wax, silicone rubber, birch wood, heat lamps, 122 x 28 x 18cm. Photo by Dennese Victoria. Image courtesy of the artist.

Your solo exhibition If time is an arrow, what is its target (2023) at Underground Gallery in Manila revolved around processes of heating, cooling, and melting, phenomena tied to spatial atmospheres and shifting experiences of time. How did this exhibition come about, and what ideas were at its center?

One central idea is how medium can be substance, center, and channel. I am interested in materials, which include objects, images, language, and space, as processes or memory. I am interested in what we look for when we look at certain materials, objects, or images, and in how we expect them to behave. I am interested in what is observable and intelligible to us.

I was also thinking through these questions in the context of exhibitions as a form or site with a specific relationship with time. Exhibitions are so short! And unlike music and film, they are rarely remounted or exist beyond documentation. Even texts and moving image works are limited in their space, time, and audience, inaccessible in person or online. I find this difficult and compelling. So I find myself exploring the trans/formation of materials, images, spaces, and time within the context of exhibitions and their audiences. Conversely, I also see this as a way to point away from the exhibition, alluding to what occurs outside/elsewhere.

Lesley-Anne Cao, Amphibian palm (For measuring the wind) (detail), 2024, installation with glass tank, mirror, glass weights, machine embroidery on gazar, acrylic box, wave makers, relay timer, water. Installation view of “Weather-world”, 2024, Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong. Photo by Ray Leung. Image courtesy of artist and Blindspot Gallery.

Lesley-Anne Cao, Dreams of speaking (Book for weeds) (still), 2020, single channel HD video, 7min 16sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

In works such as Amphibian palm (2024), Fold, fall, drape, gather, rip, wrap, crease, cling, fly, (2022), A song plays from another room (2021), and Dreams of speaking (Book for weeds) (2020), you submerge or reconfigure books using glass tanks, wavemakers, satin, mirrors, waterproof paper, and sound. What keeps returning you to the book as a form?

My work often engages with things that are omnipresent, recognisable, with a long history, and active evolution. Books, like instruments, furniture, photographs, water, and other elements that recur in my work, are deeply connected to the body, which connects them to ecological phenomena.

Those works were inquiries into the book’s material and geopoetic aspects where I reimagine how the object can exist alongside external or environmental forces. The book can be a medium through which we can imagine ways to embrace or endure threats of deterioration and loss in relation to the extremes of our socio-political and natural climates. But my projects involving books begin with and revolve around the questions of what a book is, what reading is, what materials are legible and intelligible to us.

Lesley-Anne Cao, Untitled (When the cup), 2017, text, grass, 17.4 x 5.5m. Image courtesy of the artist.

Poetry and language tends to run through your work, whether in books, titles, fragments of text, or even your exhibit notes. How does language figure into your overall practice? Is it a starting point, a material, or something else altogether?

I work with language mostly as material that is visual as text or mental pictures, aural and sonic, physical and spatial. Words, as markers of language, initiate the act of reading and also movement. I associate this reflexive response with music and noise, with the fragile, massive or sprawling. I find that some ideas are best fleshed out visually as text and/or articulated in words. And the involvement of what could be poetry are ways to employ sound, picture, structure, or movement.

Lesley-Anne Cao, Arrangement (490 flowers, 67 A. Mabini), 2020, digital print on satin, 320 x 101.6cm. Image courtesy of Mind Set Art Center.

Lesley-Anne Cao, A hundred times ajar, 2019, inkjet print on Tecco FineArt paper, frame, 111.7 x 70.6cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

In works such as Arrangement (490 flowers, 67 A. Mabini) (2020), A hundred times ajar (2019-) and Hard and soft prayers (2021), you employ strategies of archiving and cataloguing. What draws you to these acts of collecting, and in what way do they shape the meaning of the work?

I am drawn to collecting and cataloguing because embedded in these practices are notions of value and care. They require an imagination of a future or futures. Ideas and processes of growth, change, and decay are perceptible and inevitable. In these projects, I ruminate on what is detritus, domestic, momentary, peripheral, or preparatory. I think archives, especially in institutional contexts, can seem quite concrete. But they are mutable and in progress. And beyond engaging with the collections or catalogues, these forms and approaches in these artworks help me enable a body of work that is iterative and continuous.

What are your hopes for your own local art scene, and regionally as well?

I hope that there can be more writers and critics in the Philippine art scene, which cannot happen without consistent opportunities to publish and to earn enough income to sustain a practice. Of course, these factors are entangled with readership. When I graduated in 2014, the standard fee for writing a gallery exhibition text was PHP 5,000 and remains so 11 years later, with some galleries even paying less than that. I wonder about the kind of art history we are writing.

I also hope that we can have more opportunities to collaborate and develop relationships within the region. Though I appreciate their efforts, the institutions that have consistently supported local projects tend to not be from the region. I wish more bridges can be made accessible to those whose practices may be more aligned with our neighbors.

I wonder about the kind of art history we are writing.

Are there any upcoming exhibitions/projects that you would like to share?

I am working on a new iteration of Amphibian palm for ‘Transoceanic Perspectives’, a group exhibition opening in November in Almeida & Dale in São Paulo, Brazil, curated by Yudi Rafael and Carlos Quijon, Jr. I am currently developing ideas for two solo shows next year at Artinformal (Manila) and A+ Works of Art (Kuala Lumpur). I am also writing something on three analogous and converging artistic practices to be published later this year or in early 2026.