Fresh Face: Richie Htet

Presenting gender as myth

A&M's Fresh Face is where we profile an emerging artist from the region every month and speak to them about how they kick-started their career, how they continue to sustain their practice and what drives them as artists.

Richie Htet.

Richie Htet reclaims queer Burmese representation through his fluid depictions of the human form. The Yangon-based artist combines his fashion background and Burmese mythology to translate an emphasis on appearance as a rebellious front against gender binaries and heteronormativity.

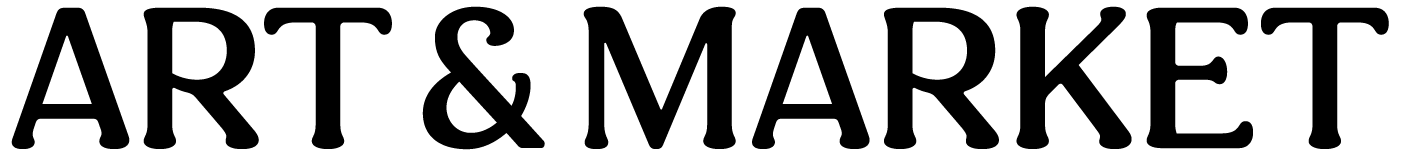

Richie Htet, Divine Reflections, gouache on watercolour paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

Richie Htet, Burmese Vamp in Green, 2018, colourpencil on drawing paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

After his undergraduate studies in Fashion Illustration from the University of Arts London in 2017, Htet was unsure about pursuing a career in art. Concerned about the uncertainties of a career in the fine arts industry, the half-Bamar, half-Indian artist returned to Yangon after graduation and worked as a stylist and art director in a women’s fashion magazine. However, the artist later participated in a duo exhibition titled I’m Not Trying to Seduce You (2018) with fellow fashion illustrator Calum Minuti at Myanm/Art, Yangon. Htet’s focus on the Burmese femme body piqued the interest of Nathalie Johnston, the founder of the gallery space. Htet was commissioned by Myanm/Art and &PROUD shortly after to create an art series based on his experiences being queer in Yangon. In 2019, Htet decided to become a full time artist, participating in A Chauk: A Solo Exhibition (2020) at Myanm/Art, Essentialist Images (2020) at Richard Koh Fine Art, Singapore and The Foot Beneath The Flower: Camp. Kitsch. Art Southeast Asia (2020) at NTU ADM Gallery, Singapore.

Richie Htet, Dream of a Chit Nat Thar (Cupid), 2020, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist.

A pioneering queer art exhibition in Yangon, Htet’s first solo show A Chauk: A Solo Exhibition (2020) eroticised ancient folklore to question the origins of queer stigmas. Htet subverts the prevailing LGBTQI+ tropes as frivolous and conniving in Burmese popular culture, thus choosing a title that simultaneously reclaims and rejects the label အခြောက် (a chauk) or a derogatory term for feminine men. In a celebratory exploration of the male nude, the artist makes clear that the true myth lies in the artificial constructs of gender and sexuality.

Richie Htet, BITCH BETTER HAVE MY DEMOCRACY, (2021), gouache on paper, 74 x 54 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Htet’s art style has not only been in the frontline of queer activism in Myanmar. The artist has also used his art to protest against the military coup that occurred on 1 February, 2021. BITCH BETTER HAVE MY DEMOCRACY (2021) portrays a female warrior wearing historical armour defeating a belu, a malevolent man-eating demon, dressed in a military uniform of the Tatmadaw, or the armed forces of Myanmar. Mythologies are sources of cultural wisdoms and by inserting queer representation and present-day power struggles into these generational narratives, Htet teaches a necessary lesson on inclusivity, justice, and resistance.

Interview

Richie Htet, Belu Si, 2020, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist.

Could you talk about your background? And at what point in your life did you decide to pursue a career in art?

I grew up in a half Indian, half Bamar household. My father is of Indian descent and my mother is of mixed Burmese descent. You can see my work is often inspired by themes of this hybridity. Although it is clear to me in retrospect that I have always wanted to become an artist, it was not until 2019 that I took the first step in becoming a full time artist. I knew I was unfit for a conventional career, however I was bogged down by prevailing ideas of success and what it means to get there.

Richie Htet, Tag! You’re It, gouache on watercolour paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

Could you share how you’ve maintained your practice after graduation? What are the important factors that kept you going?

I did not start seriously creating work again until two years after graduation. Since then I have consistently been trying to grow as an artist. I have an urge to create, I cannot go for long periods of time without drawing something. My ideas and inspirations would haunt me. I guess it's just easier now that I’ve devoted myself to cultivating my art to maintain my practice.

“Characters from folklore coloured my childhood and I wanted to instrumentalise these characters and reinvent their purpose.”

Richie Htet, Dream of the Golden Deer, 2020, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist.

Richie Htet, Dream of a Flower Eating Ogress, 2020, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist.

How did the opportunity for your first solo show, A Chauk: A Solo Exhibition at Myanm/Art come about?

I think the conversation for a solo show began after some of my illustrations from university were included in a queer group exhibition. There was surprisingly a lot of interest in my very erotic queer pieces and Nathalie, the founder and curator of Myanm/Art decided to give a show where I could expand on the themes and imagery of these smaller works.

What was the process like preparing for it? Have you had any difficulty organising queer-themed exhibitions?

I was lucky to have both Nathalie Johnston and &PROUD supporting me. My solo show coincided with the Yangon gay pride and the team at &PROUD were kind enough to include my show as part of their event programme during Yangon pride. All the technical stuff was all handled by the gallery. The only difficulty I had was with myself in finishing the work on time. I am a slow worker and have been trying really hard since, to improve my time management.

How have you used folklore imageries to negotiate queer identities?

I am interested in stories and mythology. Characters from folklore coloured my childhood and I wanted to instrumentalise these characters and reinvent their purpose. I want to teach people about acceptance, positivity and understanding when engaging with the LGBTQI+ community through popular culture. One of the stories I am drawn to is the chase of the golden deer in the Ramayana. It is also one of the most elaborate and complex dance sequences within Burmese theatre. I often depict this scene with a homoerotic subtext, reframing it as a pursuit for queer love.

Richie Htet, Horse Around, gouache on watercolour paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

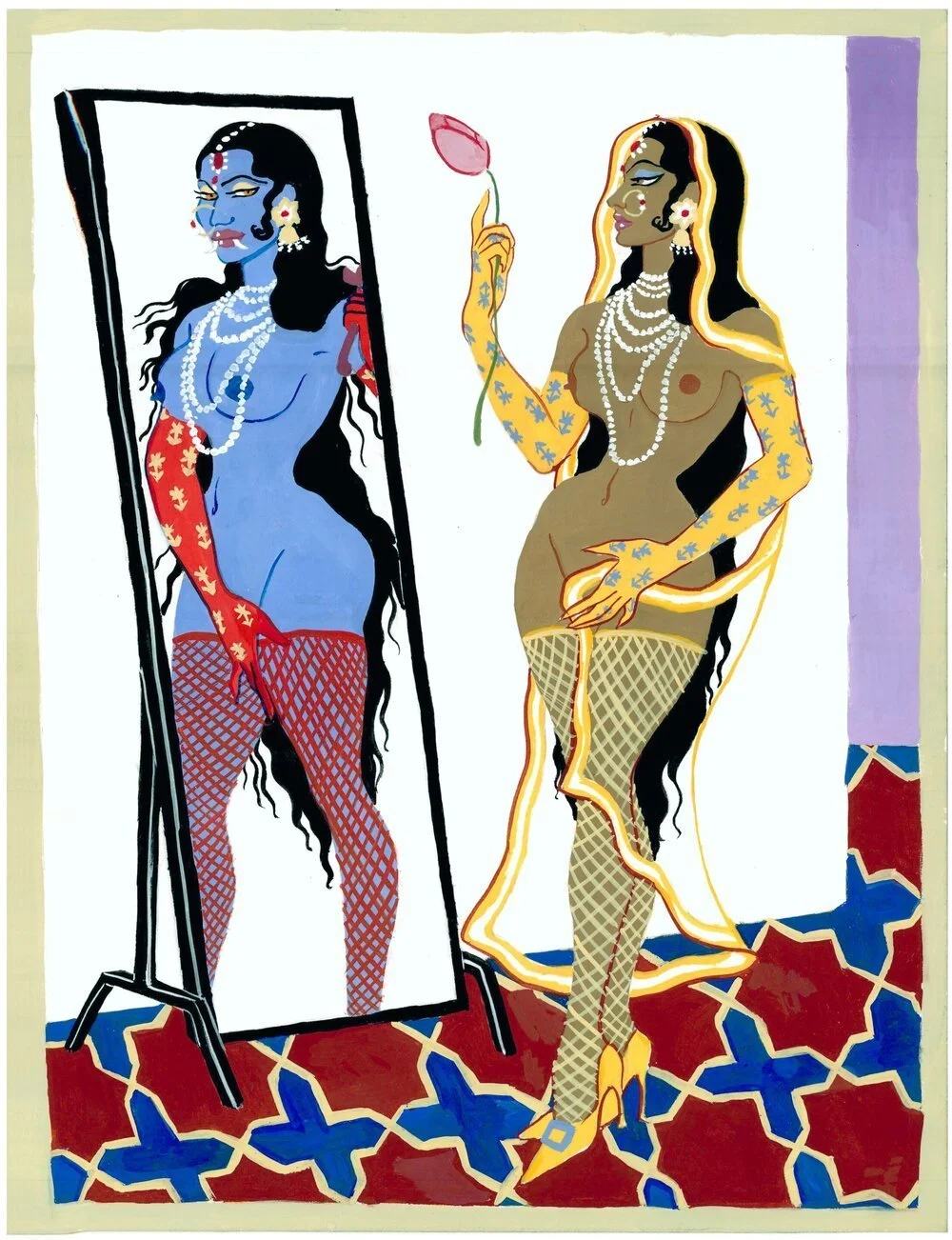

Richie Htet, Before the Wrestling Match, gouache on watercolour paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

What was one important piece of advice you were given?

Someone recently told me: “time to shit or get off the toilet”. I guess what it translates to is to seize the moment and not waste opportunities and the time that I have been blessed with, especially when my peers in Myanmar do not have the same luxury.

Richie Htet, Burmese Vamp in Blue, 2018, color pencil on drawing paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

In what ways has your background in fashion illustration influenced your art, especially in depicting the human form?

I love human bodies and I love fashion. Naturally, I would want to depict things that I find beautiful and interesting. Clothing is an important part of my life and I want the figures in my work to embody the same attitude.

Who has been a mentor or an important artistic influence? And why?

Nathalie has been an important figure in my development as an artist. Without her encouragement and support I would not be where I am today. She pushes me to become a better artist everyday.

I have recently become interested in surrealism. Reality has become increasingly surreal and naturally it bleeds into my work. Elsa Schiaparelli is one of my favourite designers and her work combines both fashion and surrealist art. My art is about my queerness and my ethnicity, so both Indian miniatures and Burmese manuscript paintings, as well as queer bodies play an integral role in the images I want to make.

Could you share your favourite art space or gallery in your country? Why are you drawn to that space and what does it offer to you or your practice?

My favourite art space in Myanmar used to be Myanm/Art. But unfortunately due to the worsening situation in Myanmar, it is no longer safe to have a physical space.

The ongoing coup poses a humanitarian crisis in Myanmar, including the artistic community. What are your hopes for your own local art scene, and regionally as well?

In an incredible twist of fate, the coup has catapulted artists from Myanmar to international exposure. This was not afforded to us before. It is a silver lining in a time when artists are persecuted for simply doing their job. There is a new appreciation for art from Myanmar artists domestically and internationally. This is a huge step forward from before the revolution, when opportunities were few and far between. My hope is that we can keep this momentum, which I have no doubt we will for the future.

Are there any upcoming exhibitions/projects that you would like to share more information on?

I have an upcoming residency in Paris starting June. This would be my first residency experience and I am super excited for it and the work I will be creating.