The Rip in the Machine

On Filipino web artist Chia Amisola and her internet ambiences

This is a winning entry from the sixth Fresh Take 2025 writing contest. For the full list of winners and prizes, click here.

A&M’s Creative Edit is where we publish a creative response to an ongoing exhibition or display every month. These pieces can take a range of forms, from ekphrasis, to poetry, microfiction, creative nonfiction and more.

On 11 June 2025, Living Web Institute hosted an “internet home tour”, where the then San Francisco-based Filipino artist Chia Amisola started by sharing artifacts in her bedroom: two desks and the clan of computers on them (for work and otherwise); anime keychains, plushies, and literature; a statue of Mother Mary she ordered from Amazon; vines and serpents of electric cords (“my place is very messy,” she admits); on the gorgeous wooden floor, a pair of old white monitors. When this was over, Living Web co-hosts Matthew Prebeg and Kristoffer Tjalve let Chia admit us into her website everythingi.love. On one hand it is a glorious curriculum vitae, on the other it is—like her lush bedroom—decorated, epistolary, and alive.

One year prior to the web tour, I discovered Chia while browsing through X, where she posted an online call for an “internet ambience” workshop she was hosting in California. The internet I knew was anything but ambient: I swung between my private social media and the search engine, and even then, the shores I came across were polluted with AI-generated images, bot accounts, and headlines of warfare almost always defending empire. I began to scorn the phone screen, but I could not turn my eyes away from it. When I finally experienced Chia’s web art and the Cascading Style Sheets sizzling in its script, it was as though I was caressing the internet for the first time again.

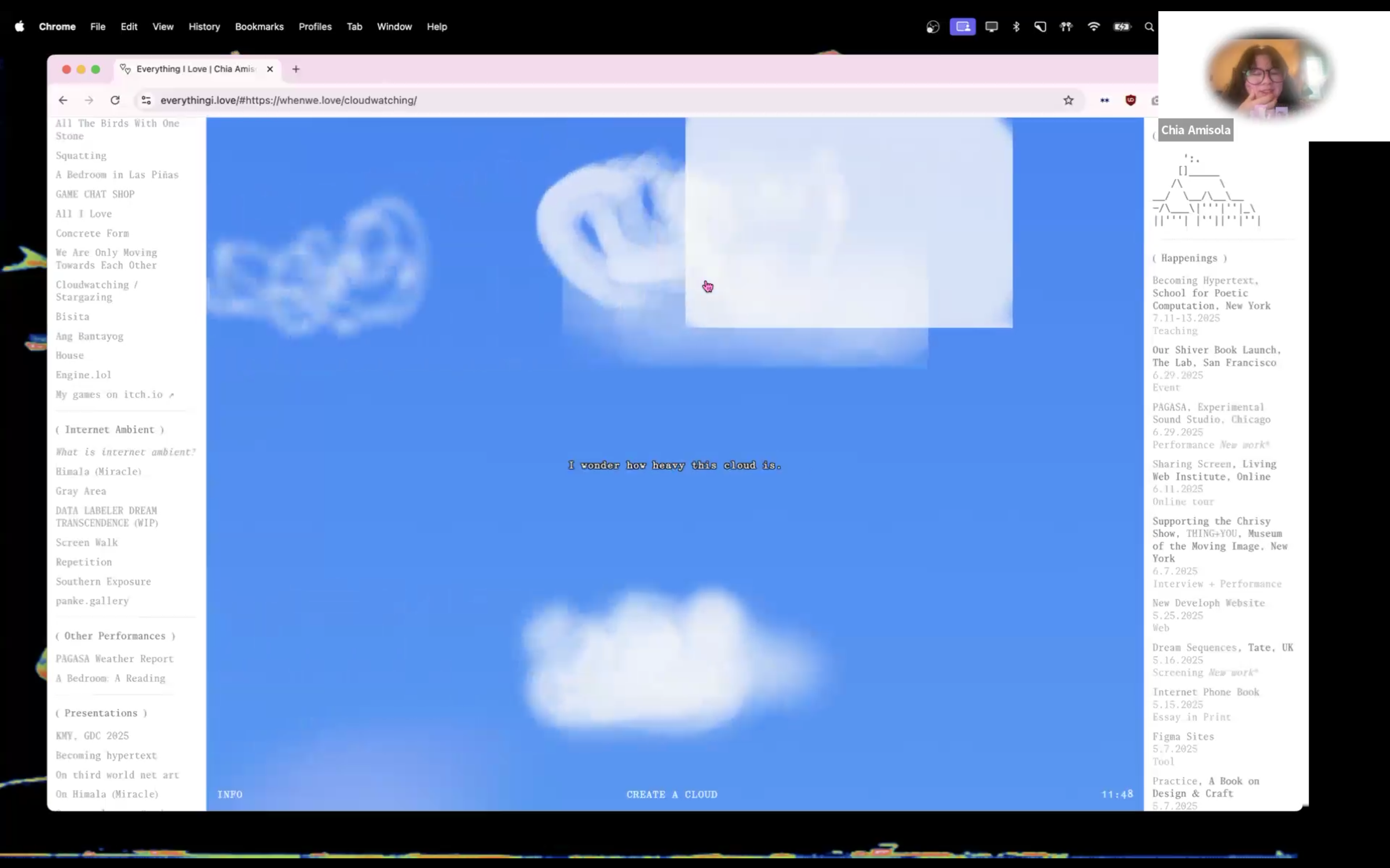

Some of Chia’s works I found, including cloudwatching / stargazing (2023), were web programs that would either work or tell you to come back later, depending on your machine’s local time. The programs let you draw a cloud or imbue a star with something you want to say to someone, before saving what is scribbled and adding it to the digital firmament. On chia.design, another sea splashed with her works, I fell into one of its whirlpools and discovered Landscapes. I accidentally pressed on a blank surface of the webpage and a window popped open, revealing a scene of clouds in motion, as though Chia had given me a shard of sky.

Chia showcasing cloudwatching, 2023, from her Living Web Institute show. Image courtesy of the Justin Cruzana.

From my first encounter with Chia’s work, I would pluck from the pistil of her oeuvre and treat it like the lyric. I read the persona in her web art, sensed it having at least once knelt in the confession box. Concerns of identity and its legibility loom over Chia’s corpus: she was born in the Philippines, then she moved to the United States to study at Yale. For Living Web Institute, she showed her work Forms (2024) and a “single purpose expressive site” called ifyouknewmeyouwouldlove.me. These were created during her assimilation into the US, while she was “trying to make [herself] legible.” In assimilating, in “becoming” American, what does one lose, what does one morph into? For an empire like the United States, whose mere political and economic sighs create fissures in other countries, including the Philippines, where I live, it is difficult to part a legible self from a lucrative one. Conquest and wealth accumulation are the alphabet; the internet is your blank page.

Yet Chia’s corpus, including her in-person performances and her web art, free and online and vacant for discovery, sheds no skin of herself. Despite having lived most of her new and current adult life in the US, her Filipino identity ripples in her in-development project Squatting. In the Philippines, the words “squatting” or “squatter” are hurled toward displaced and informal settlers, words Chia transforms from insult to endearment as she shelters the art of her colleagues within Squatting’s iframes. In this year’s Philippines Art Fair, Chia exhibited Kakakompyuter mo yan!, her curatorial project inspired by early 2000s Filipino internet and media culture. Kakakompyuter [...] shows how Filipinos and their lives have been changed by the internet, a technology whose origins begin in the American military, but that the internet, too, is changed by Filipinos, as it becomes a space for accessible media circulation and liberation.

Gender is also in the syntax of Chia’s style: her web art remains confessional and saccharine, visions of pink hues scatter over her work, and her admiration for the late actress Nora Aunor and the Virgin Mary is unabashed. Symbolically speaking, one is compelled to call the contemporary internet “masculine”: it is a fortress of surveillance, a means of consolidating state power and influence. Sadie Plant, in her seminal book Zeros + Ones, reshapes the canon of the machine and cyberspace through the lens of the feminine. From the mathematical prowess of Ada Lovelace, the first programmer, to the role of women as weavers of the Net, to even the “virtual aliens”: low-paying US migrant women working electronic assembly jobs. Chia, like Plant, champions the feminine and the feminised in her work: women, yes, but also the working third world internet, paid for a pittance by first world countries. The feminine is not only a style in Chia’s work, it is a mission statement: if the stony bulwark of the internet is a body, then so can its gender bend to our will, with an accessible cyberspace for all of us just over the horizon.

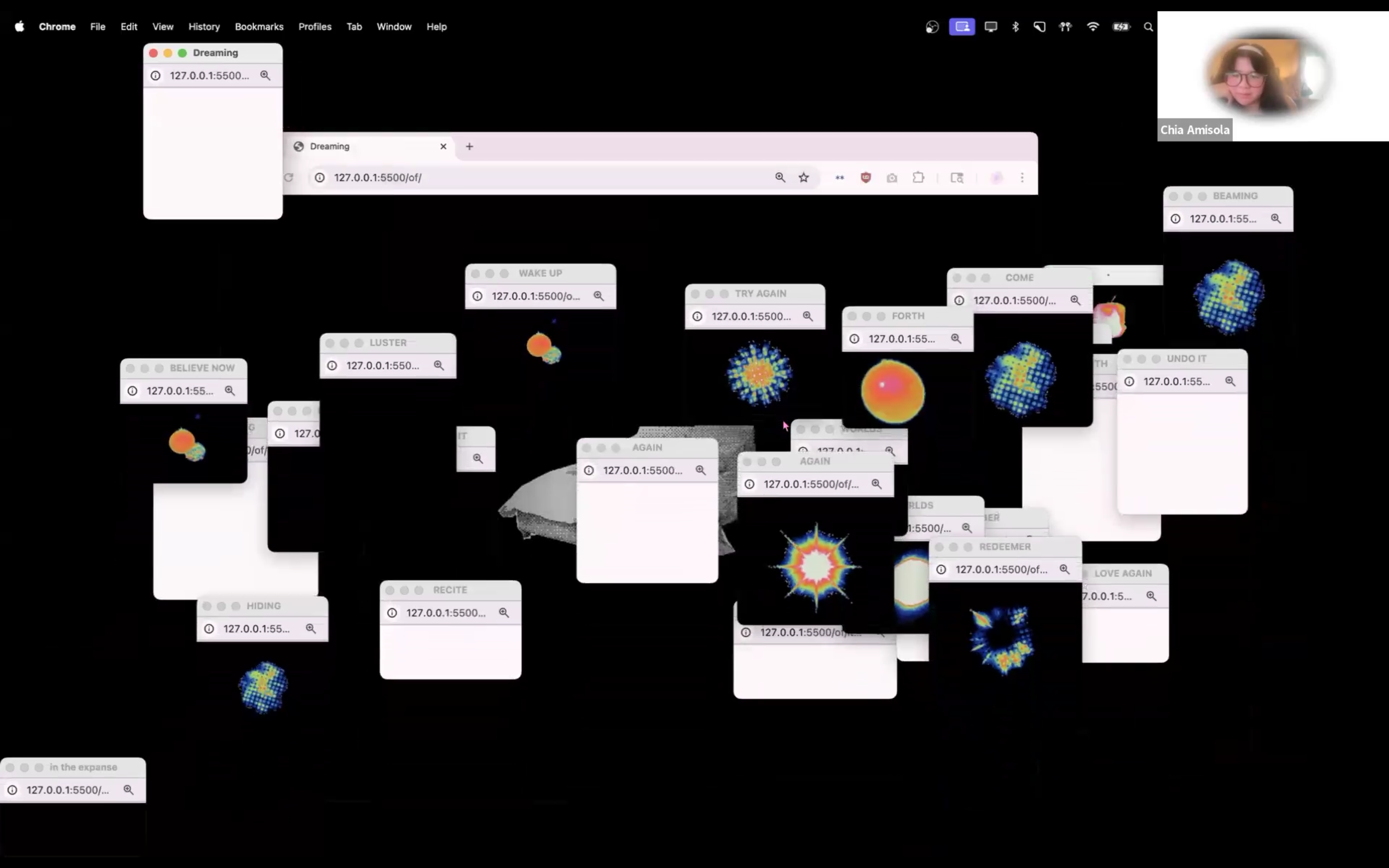

Chia performing Dreaming during the internet web tour. Image courtesy of Justin Cruzana.

Later in the show, Chia demonstrates a lite version of her performance Dreaming. When she plays sounds on a keyboard, pop-up windows with the shape of objects, lit like x-rays, float on her screen. She begins, a pink cloud and an apple reveal themselves. She tries to show additional desktop screens but her computer begins to lag. Chia presses more keys and more windows appear, but by then not every image loads. Movement once smooth staggers. “I don’t know if my laptop can handle this right now.” Chia says. She laughs and seems embarrassed but keeps pressing. In performance art, the durability of the performing body reminds us of the humanity in the artifact. Like so, it is the rip in the hypertext, the buffering self in the operating system, that makes the computer mortal, legible to us. Chia’s work is stubbornly hopeful; that in the realm of the contemporary internet, there can still be space for the self to run wild. For what it’s worth, I am starting to have hope, too.