Conversation with Charwei Tsai

Art in union with faith and devotion

Charwei Tsai. Photo by Marilyn Clark. Image courtesy of Islamic Arts Biennale.

Charwei Tsai (b. 1980, Taipei) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Paris and Taipei. Highly personal yet universal concerns spur her practice, which explores the complexities of cultural beliefs, spirituality, and transience. Recently, Charwei has exhibited at the Islamic Arts Biennale (2025), Palais des Beaux-Arts de Paris (2024), Gwangju Biennale (2023), and Mori Art Museum (2022), among others. Her works are in major collections, including Tate Modern, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and M+. She also publishes Lovely Daze, a curatorial journal held in the libraries of MoMA and Pompidou.

On the occasion of her solo exhibition Tofu, Incense, and Sky at Blank Canvas, Penang, I invite the artist to reflect on how her practice has evolved in the last two decades. In this conversation, Charwei offers insight on her collaborative mode of working, the artist book as a medium, and her relationship with faith and wisdom traditions.

Charwei Tsai, Tofu, Incense, and Sky, 2025, exhibition view at Blank Canvas, Penang. Image courtesy of the artist and Blank Canvas.

The exhibition at Blank Canvas centres on three important video works Tofu Mantra (2005), Sky Mantra (2009) and Incense Mantra (2011) where you inscribe the Heart Sutra on different objects. Across your practice, you have engaged with Buddhist texts in ways that take on different forms, as performances, videos, photographs, and as calligraphy on physical objects. Does the meaning change depending on the form, such as when it is experienced as a video or photograph as compared to a live performance?

My intention with this series of work where I write Heart Sutra on ephemeral materials is to internalise the text as a part of the body’s memory. This remains the same throughout the different forms of presentation, but the sensation of perceiving the different formats may feel different. For example, as part of the exhibition programme, I will be presenting a performance titled Edible Mantra for the first time where after writing the sutra with edible ink on the tofu, the audience is invited to eat it. This way, the text transforms and becomes a part of our bodies and cells. It will be a very different experience as compared to taking time to sit introspectively and watch a video work of the sutra being written on a mirror reflecting the changes in the sky.

Charwei Tsai, Spiral Incense - Hundred Syllable Mantra (detail), 2016, ink on spiral incense, installation at Biennale of Sydney. Image courtesy of Biennale of Sydney, 2016.

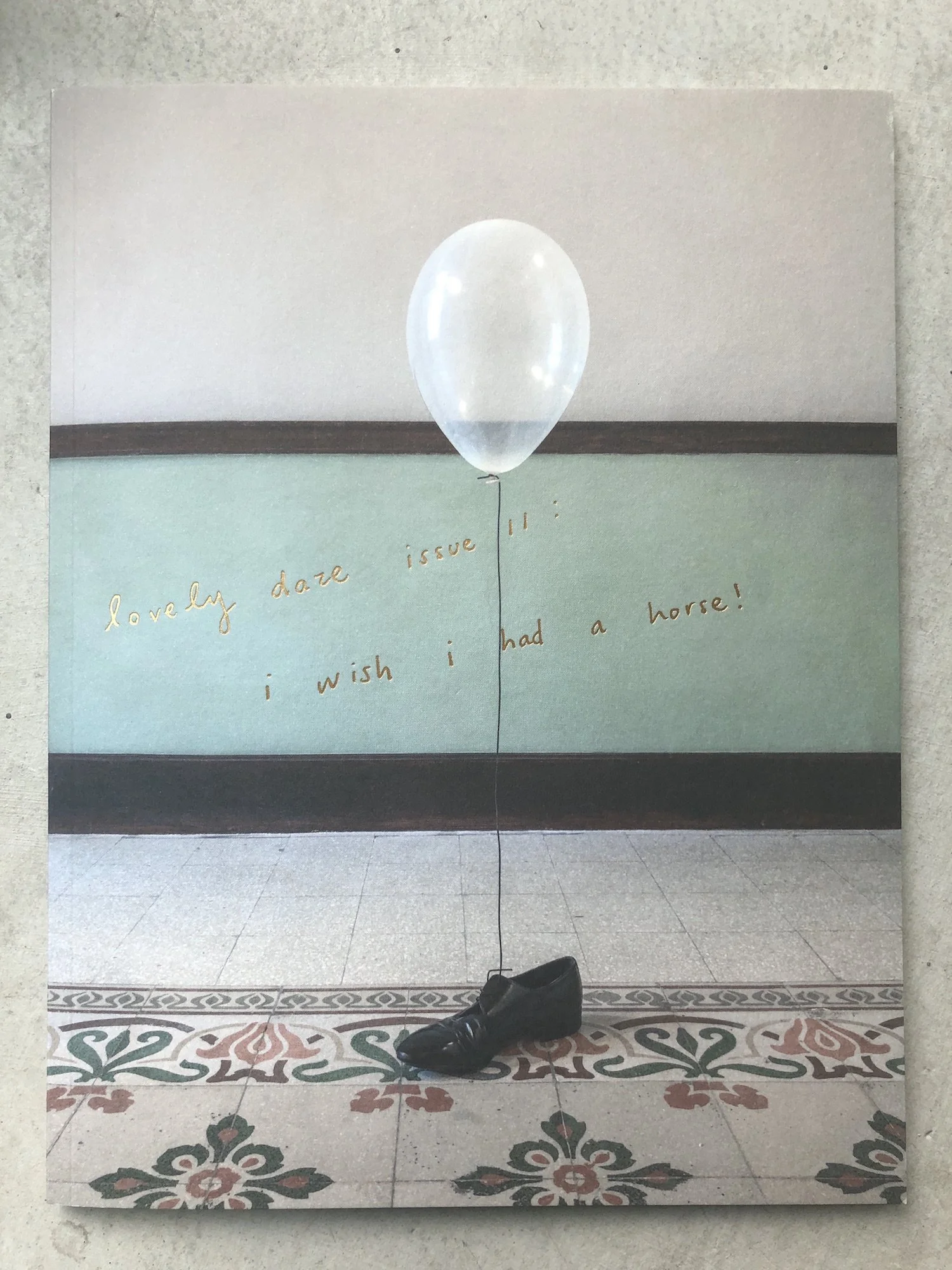

My next question is about Lovely Daze, a curatorial journal of artist writings and artworks you founded in 2005. What sustains your interest in continuing this project? What is the main challenge you faced in organising or keeping it going?

Lovely Daze is my heart project where I publish artworks and writings by artists whom I admire and am inspired by. Like many zines, it has been a big challenge to sustain financially. The publication is very well received, but even if the entire edition sells out it would never pay for itself. It is a challenge to cover the printing and shipping costs, let alone traveling for book fairs, book launches or to hire assistants. However, I would still like to figure out a way to keep it running in the future, by applying for grants or starting an online platform. It is something I love to do, to share other fellow artists' work, especially artists from less-explored regions such as Mongolia and the Himalayas.

Cover of Lovely Daze Issue 11 – I Wish I Had a Horse! Image courtesy of Charwei Tsai.

Display shelf with copies of Lovely Daze, presented in Tofu, Incense, and Sky (2025) at Blank Canvas, Penang. Image courtesy of Blank Canvas.

Has your relationship with the journal or artist book as a format changed with development in printed and digital media in the last 20 years?

As an artist myself, I have rare insights to connect with other artists on a personal level and to witness how they live their lives in an intimate way. This closeness of friendships offers an alternative perspective of looking at the works. Around 2013, when social media was on the rise, I moved from New York, one of the major centres of artists’ books at the time, to Saigon for personal reasons and felt very isolated. Also at this time, digital media did start to replace printed media. Many of the artist’s zines that started at the same time as Lovely Daze have faded out.

In 2019, after I moved to Taipei and my mind settled back into creating works again, I felt a strong connection with the artists’ community once more. That was when I published the most recent issue “Wish I had a Horse”. Inspired by a famous Mongolian song where the youth express how they felt losing touch with nature. For this occasion, I invited two Mongolian artists, Ganzug Sedbazar and Davaajargal Tsaschikher to Taipei to create two performances for the book launch.

Now I am in the middle of producing the next issue, which is focused on female artists who have dedicated their lives in community work beyond just an art project. This issue includes Yee I-Lann (Malaysia), Melati Suryodarmo (Indonesia), Mella Jaarsma (Indonesia), Ashmina Ranjit (Nepal), Wu Mali (Taiwan), and Eun-Me Anh (South Korea).

Charwei Tsai, That Which at First Tastes Bitter, 2025, mica pigment and ink on cotton, 395 x 758cm each (2 panels). Installation view at Islamic Arts Biennale 2025, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Photo by Lucia Novoa.

Recently, you presented a new installation That Which at First Tastes Bitter (2025), commissioned by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation for the Islamic Arts Biennale 2025. What drew you to the Kufic inscription your work references?

I was invited by the biennale to create an artwork in response to a 10th century ceramic plate from Samarkand with Kufic inscription, in the Louvre Museum’s collection. I spent almost two months studying with a calligrapher teacher in Jeddah to write the Arabic word “Al halim” in Kufic script. It is the first word on the plate, and can be interpreted as “forbearance” or “patience” or “aspiration”. The idea is to create a constellation of the word in a large painting that surrounds the plate as an accompaniment for the pilgrims from all around the world who pass by Jeddah on their way to Mecca and Medina.

Are there connections between different calligraphic or faith traditions that resonated with you?

My Arabic calligraphy teacher, Abdulrahman Elshahed, told me that the old calligraphers who copied the Koran all their lives would collect the shavings from their reed pens daily and request in their will to be buried with these shavings covering their bodies, touched by words of God. I believe when art is in union with faith, devotion, and the intention to benefit the collective wellbeing, it conjures a power that is much greater and much more interesting than a pursuit and display of individual genius.

Charwei’s studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

Charwei Tsai, in collaboration with the community of Licchavi House, Ancient Desires – One Taste, 2024, installation of ceramics and offerings. Commissioned by Licchavi House, Kathmandu, Nepal. Image courtesy of Licchavi House.

Could you describe your studio or workspace? And has it evolved over the years?

I have not had a studio practice. My studio is a space for research and planning, and sometimes it opens up for meetings and gatherings. Most of my productions are created either on site at exhibition spaces or at my collaborators’ ceramic, textile, printmaking, or video editing studios with specialised facilities. Only smaller works such as drawings or prototypes are made at the studio. This way of working allows me to collaborate with a wide range of communities with special knowledge and skills. In the last few years, I have worked with craftswomen communities from the United Arab Emirates, Mongolia, Indonesia, and with ceramists in France and in Taiwan. Collaboration has become a part of my method for production.

Ganzug Sedbazar, Kissing the Earth, 2025, video (still), 8min. Produced by Charwei Tsai and filmed by Khoroldorj Choijoovanchig. Photo courtesy of Charwei Tsai.

Are there any upcoming exhibitions or projects you wish to share?

I was just in Mongolia, where I filmed a performance by Ganzug Sedbazar in the steppes. I met Ganzug seven years ago when he was exhibiting in Taipei. We have travelled together extensively with other friends in Mongolia since and this is our third collaboration. I took an unprecedented role in our current project as a producer. I am not sure if there are many examples of artists producing other artists’ work. I simply have the urge to capture and share his practice with the rest of the world.

During the planning of the project, Ganzug said he has always wondered why I take so much interest in him and his performance. I explained that I am inspired by his heart connection with his land. During our travels through the vast landscapes in Mongolia, each time we stopped the car, he would pay homage to the land by prostration or offering milk, vodka, incense, fire, smoke, or songs. Everything he does or says is consistently in reverence of nature.

Once we were sitting on the grassland, I made a careless comment about the filth of animal dungs surrounding us. He was angry with me and explained that dung is not something dirty but rather it is nutrients for the land and fuel to make fire. I realised that this is true not only for ecology to regenerate what is considered as waste. On a mental level in Buddhist teachings, to regard what we dismiss as wasteful or unpleasant emotions and transform them into wisdom is also a core practice. These special moments with Ganzug are integrated into our next video project, Kissing the Earth that will be a part of my upcoming solo exhibition at TKG+ in Taipei, opening in November 2025.

Charwei Tsai, A Temple, A Shrine, A Mosque, A Church, 2022, gold ink on hand-woven mats by craftswomen from Al Ghadeer, Abu Dhabi, 300cm x 5 pieces (orange), 150cm x 4 pieces (green), 150cm x 4 pieces (purple). Commissioned by Art Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Lastly, what do you think has been your purpose? Has it remained steadfast or evolved over the years?

My intention of making art is to familiarise with what is called the three marks of existence in Buddhist terms: annica, anata and dukha. They contend with the understanding and acceptance that everything is impermanent, compounded, and interdependent, and as emotional beings, we will never feel fully satisfied. This is the aspiration for every project that I create, whether it is on my own or collaboratively. My practice has evolved over the years. It began from seeking this truth solely through the Buddhist tradition as revealed in the sutras, and has expanded to the same understanding of interdependence and compassion that is found in a wide range of wisdom traditions.

Charwei Tsai’s Tofu, Incense, and Sky is on view from 5 July to 31 August 2025 at Blank Canvas, Penang. The artist will be presenting a live performance Edible Mantra on 23 August 2025 at 3pm.