Conversation with Arin Rungjang and David Teh

Artistic Directors of Thailand Biennale Phuket 2025

Arin Rungjang and David Teh.

The itinerant Thailand Biennale returns for its fourth edition in late November 2025, set in the resort island of Phuket. Initiated by the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture (OCAC), the Thailand Biennale aims to decentralise contemporary art and reimagine provincial destinations for visitors and locals. Thailand Biennale Phuket: Eternal [Kalpa] is helmed by Artistic Directors Arin Rungjang and David Teh, alongside curators Hera Chan and Marisa Phandharakrajadej.

In this conversation, I speak with Arin and David to get a teaser of what audiences can expect. They unpack the biennale’s key themes as well as how artists are responding to Phuket's rich history, natural environments, and its current reputation as a tourist hotspot.

Taiki Sakpisit, The Spirit Level (still), 2023, two-channel video installation, 4K, Colors Black & White, 16:9, Stereo, 21 minutes (loop). Image courtesy the artist.

Could you say more about the title Eternal [Kalpa]?

Arin Rungjang and David Teh (AR & DT): The title points to an old Hindu-Buddhist notion of time, but one that is nevertheless still current in Thailand. Kalpa, which translates to mean one lifetime of our universe, is used quite often in everyday speech. Thinkers in many different fields are trying to go beyond the habits of a modern, scientific worldview, even as linear time and rationalism still shape our daily lives. But that anthropocentric logic does not replace the older cycles and rhythms of life. Artists today are attentive to different “time signatures”. We also see this in the celebration of indigenous, customary, and other non-Western kinds of knowledge. The biennale title suggests a shift from the linear, one-size-fits-all notion of progress, to a more diverse, more inclusive understanding of time.

How does it relate with the themes explored and the context of Phuket, which is known as a tourist resort destination?

AR & DT: Nature has its own timescales. Phuket’s topography is a product of geology, shifting tectonic plates on one side and the slow build-up of coral on the other. Like Singapore and the Straits in Southeast Asia, its history was shaped by the winds. We may be less attuned today to these non-human tempos, but they are always there. People go to tropical islands to be exposed to the elements and the seasons. The alarm clock and train timetable can be swapped for sunsets, the tides, perhaps a full moon. Last year Phuket received 8.65 million foreign visitors. Of course, this tourism has an industrial scale and a relentless rhythm which tends to drown out local ones. It also impacts the other non-human species which make Phuket such an inviting place.

Exploring Surin Beach, Talang District, Phuket — in preparation for a site-specific public artwork by Nolan Oswald Dennis, an artist from South Africa, supported by Phuket City. Surin Beach, with its fine white sand and clear waters, is one of the island’s most iconic shores. The area is also the planned site for the Glass Terrace project, envisioned as a new beachfront landmark combining leisure, culture, and community space. Image courtesy of Marisa Phandharakrajadej.

A visit to the Pearl Theatre, one of Phuket Town’s historic cinemas. Built in the mid-20th century, the place was once a cultural hub where locals gathered for film screenings before the era of modern multiplexes. Though no longer in operation, its architecture and history remain a reminder of Phuket’s golden age of cinema. Image courtesy of Marisa Phandharakrajadej.

What are a few of the key sites or locations? Why are they chosen and which site you are particularly excited about?

AR & DT: The exhibition will unfold across a range of civic, post-industrial, and former commercial sites, focused around Phuket Town. One venue is a former power station of an ore processing site in the foothills, not far from town, a remnant of the tin mining that dominated the island’s economy from the 19th century. Many artists are interested in that extractive history, but a peculiarity of Phuket is how sharply it pivoted to tourism in the mid-1980s. Today, its economy is almost totally dependent on leisure and hospitality. We like to think these activities are friendlier to the planet, but they have drastic effects on resource use, the environment, and communities. Over-tourism is a serious issue.

We are also excited about a place called the Pearl Theatre, in the middle of town. Though now disused, it used to be a site for entertainment. It was a kind of hostess club for men, a movie theatre, and more recently a modern-day amusement hall, filled with trompe l’oeil backdrops for taking selfies. Here we are exploring the body, especially gendered bodies, as a threshold or hinge between work and desire, between economic value and our aesthetic, sensual life.

Maree Sheehan and Alex Monteith, site research documentation for coastal biodiversity and environmental protection, Koh Surin, Thailand. Image courtesy the artists.

Could you talk about the commissioning process and mention a few highlights to look out for?

AR & DT: There are around 50 new works being created, it is an ambitious project! Phuket has no museums or galleries to accommodate this kind of show, so we were never going to ship in a lot of existing works. The settings give artists a chance to think differently about their practice, to address new audiences. It is hard to pick highlights, but we are particularly excited about projects from this region. Melati Suryodarmo is making a new performance piece. There is a new collective of artists and researchers, Koneksi Tamalanrea, coming from Makassar. We have brilliant storytellers digging into the island’s social and natural histories: Riar Rizaldi, Andrew Thomas Huang, Taiki Sakpisit and Chantana Tiprachart.

And there are projects exploring the ecology. Maree Sheehan and Alex Montieth, in collaboration with local artist Apiwat Thongyoun, have been studying the area’s unique mangrove ecosystem, an ecological lynchpin. The Hong Kong-based duo Zheng Mahler are cultivating the sea grass that is attracting dugongs, new migrants to Phuket. Pratchaya Phinthong is collaborating with scientists and divers to regenerate coral, by recording and redistributing the sound of healthy reefs. These projects are radically stretching the notion of hospitality.

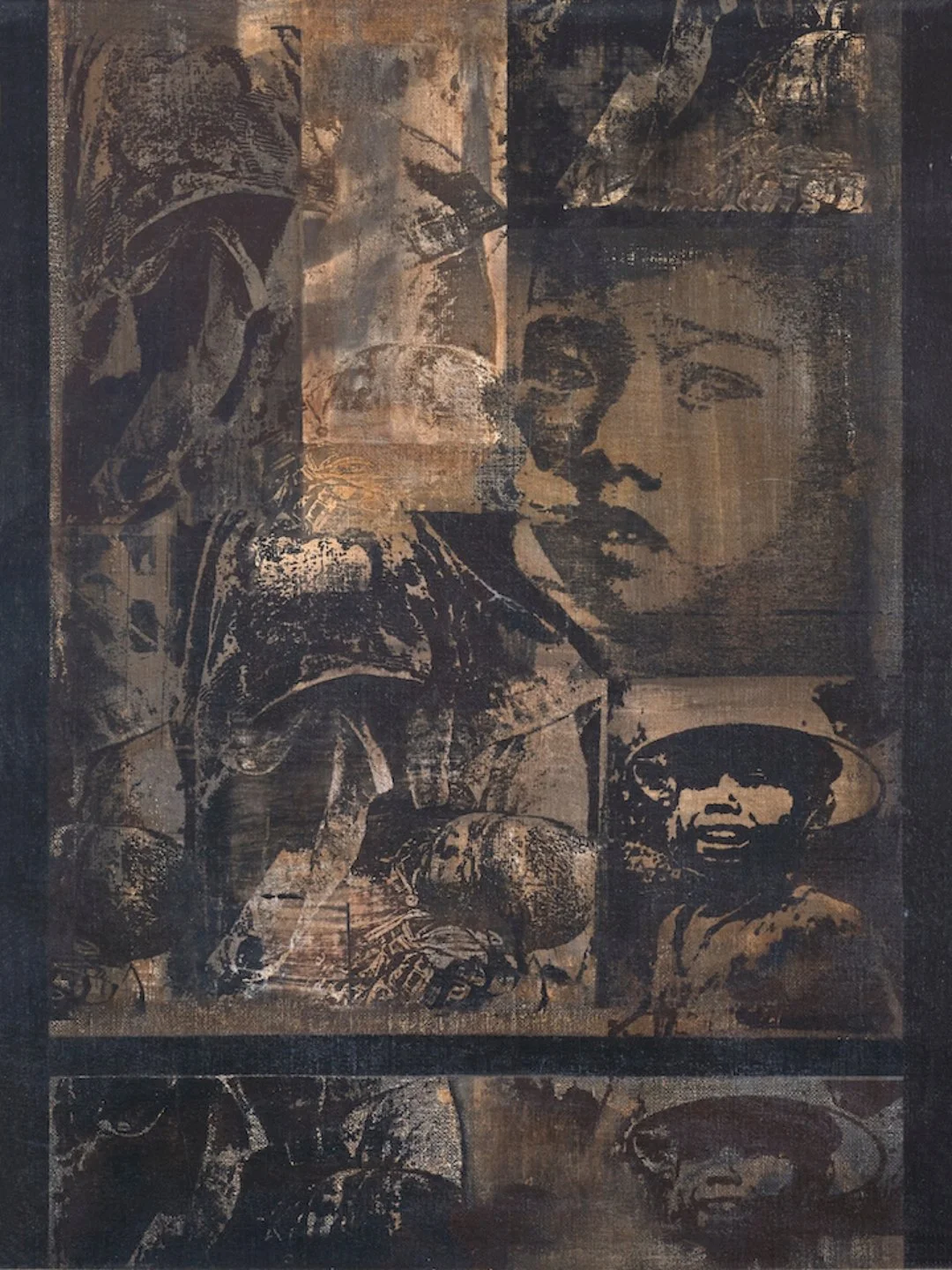

Nirmala Dutt, Anak Asia, 1983, acrylic and silkscreen on canvas. Image courtesy the estate of Nirmala Dutt.

In addition to new commissions, you are working with estates of artists such as Tomiyama Taeko and Nirmala Dutt. What connections do you wish to draw between their practices and the biennale’s context?

DT: Phuket has a rich history but does not quite have an “art history”, at least not yet. Is this something that a biennale could propose? It is one of the most internationalised places in Thailand, and unlike many provinces, its worldliness does not depend on the nation, and it is not decided in Bangkok. What kind of art history would such a place have? What larger worlds is it part of? Nirmala and Taeko were both worldly islanders. Nirmala was born in Penang, studied in England, then resettled in peninsular Malaysia which, like Southern Thailand, has a long history of South Asian exchange and migration. Though she passed away in 2016, her preoccupations are contemporary: the effects of dispossession, conflict, corruption, and heedless development spurred by nation states, on ordinary people and environments. Late in life, with her health and eyesight failing, she also made a striking series of works in response to the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami, which devastated Phuket.

Taeko’s family came from Awaji, near Kobe, Japan. Inspired by the island’s puppet tradition, for decades she traced a web of folk cultures that connect most of Asia, continental and archipelagic. She belonged to a network of progressive Asian artists campaigning for human rights, and against sexual and labour exploitation, which are still urgent issues today. These anti-imperialists insisted on Japan’s responsibility for wartime violence, so they were excluded from official art channels for decades. With her Thai activist friends, Taeko made a stunning exhibition in Bangkok in 1991. We are thrilled to be bringing that series back to Thailand for the first time, with other works highlighting her distinctly collaborative art practice.

Luana Vitra recently visited Ceramics of Phuket, a creative studio where native Phuket clay is reimagined into contemporary, functional art. Blending the island’s cultural heritage with modern design, the studio handcrafts bowls, cups, and tableware in the natural tones of tin clay, enriched with the emerald and blue hues of the Andaman Sea and the vibrant shades of coral reefs. Each piece, made entirely on-site, reflects both the timeless beauty of nature and the unique artistic legacy of Phuket. Image courtesy of Hera Chan.

This is the fourth edition of Thailand Biennale, which was previously held in Krabi (2018), Korat (2021), and Chiang Rai (2023). In what way(s) does your vision for Thailand Biennale Phuket: Eternal [Kalpa] build upon or deviate from the approaches developed in the past iterations?

AR & DT: None of the curatorial team has worked on previous editions, so we cannot speak to that.

Although the biennale is large, it is a slight operation, organisationally speaking. This is a mixed blessing: it is hard to build capacity and continuity, but each location gives the platform new energy. Of course, we are mindful of the success of the last edition. It is a hard act to follow! That said, visual art was already part of Chiang Rai’s identity. Phuket is different. For the locals, this biennale will be full of new discoveries.

Taiki Sakpisit visited the historic Sin Tek Seng family house in Phuket Town, where he met with Orawan Phetpradapsakul (Ko Ta), the present heir to the family’s cultural legacy. Recognised as one of Phuket’s oldest Chinese-Thai families, Sin Tek Seng has long preserved and passed down the craftsmanship of cultural artifacts and ritual items used in the worship of deities across generations. To this day, the family continues to produce these ritual objects for major ceremonies in Phuket, underscoring the enduring significance of their traditions and their vital role in sustaining the island’s rich cultural heritage. Image courtesy of Hera Chan.

What is your personal intention for this biennale?

DT: What I hope to achieve is to complicate the idea of Phuket. I have been going there for 20 years. It has changed a lot but its image is still pretty straightforward—sun, sand, and sea. It is an instagrammable luxury. That image excludes many stories, human and non-human. Phuket has a historical richness that is quite distinct from Thailand’s national history. It can be tasted in the cuisine, and seen in people’s faces in the local community. It is increasingly part of the island’s brand. As a publicly-funded platform, Thailand Biennale has a role to play making that diversity visible, for Thais and visitors alike.

This interview has been edited, and is presented in partnership with Thailand Biennale Phuket 2025.

Thailand Biennale Phuket: Eternal [Kalpa] is happening from 29 November 2025 to 30 April 2026.